Phnom Penh Express (12 page)

Read Phnom Penh Express Online

Authors: Johan Smits

Phirun forces a smile, “Course not. I got it off the internet and chucked in your name here and there, you know, just for a joke,” he lies, trying to sound light-hearted while his ego deflates like a punctured balloon.

“So crap that it’s funny,” she chuckles, crunching the poem into a paper ball. “You’re an unusual one,” she says, lifting her espresso. “Let’s get the check, shall we?”

Phirun is so upset, he fails to notice that Merillee didn’t touch the little chocolate perched on the saucer of her espresso despite her self-proclaimed addiction to the stuff.

***

Driving home, Phirun swears out loud. “I should never, never, never have written her that piece of shit,” he yells furiously. “When will I ever learn? When, when, when?”

Everything had gone wrong after the poem. He had asked her if she’d like to have another drink at his place and she had muttered some lame excuse about having too much work. He had then asked when they’d meet again, and she promised him that she’d call, in a tone which had sounded evasive to his ears.

In his distress he drives through the second set of red lights since leaving Pop’s Café and realises that it is safer than stopping. It seems that the surrounding traffic is anticipating just that anyway; stopping at the lights would be riskier in this town. Two things I learnt today, he thinks; never write an honest poem to a girl and never stop for traffic lights in Phnom Penh.

When he turns onto Mao Tse Tung, three policemen are blocking the street; one motions him to the curb. Already in a filthy mood, Phirun curses, slows down and steers his motorcycle to the roadside, then abruptly hits the gas, speeding past the policemen. They don’t seem to be the least bit surprised. Only one of them tries to acknowledge Phirun’s disobedience, slowly waving his orange baton and unconvincingly shouting a lazy “Hey” while his colleagues ignore the incident. As a way of not losing too much face, they’re already looking for a next victim to stop and extort. It’s the main way of supplementing their meagre salary and has become a boring routine.

A few moments later he arrives home. By force of habit he grabs his keys only to realise that there’s no longer any lock on the gate. It can only be opened from the inside. He bangs his fist on the gate and waits. After thirty seconds, he bangs again, louder. When nothing happens, he assumes the guard must be sleeping. He knows that there’s always a fifty per cent chance of that with guards, but he’s really not in the mood to deal with that now — the last dregs of his goodwill have long since evaporated. He peers through a crack in the gate and spots the young man slumped onto a plastic chair, seemingly fast asleep. He loudly rattles the gate while shouting at the guard.

“Damn! I already start to miss that lousy mutt!” he yells, thinking of Chucky. “Who would have thought that a few days ago?”

Finally he hears movement on the other side of the metal gate and it eventually slowly grinds open.

“Sorry,” the guard smiles, looking not in the least sorry.

“Why you’re sleeping?” Phirun asks, realising the stupidity of his question but wanting to convey his annoyance.

“Because I’m tired,” the guard answers.

“Then what do you do at night?” Phirun persists.

“Work.”

“Work? So you work twenty-four hours, or what?”

“Yes, I work as a night guard at night and as a day guard during the day.”

“When do you sleep then?”

“At work of course,” the guard answers, flummoxed.

When he enters his little apartment Phirun goes straight to the fridge, takes a couple of beers out and seats himself at his kitchen table. He and Merrilee should be making love right now, he laments. Instead he’s feeling utterly miserable. “The crappiest poem this side of the Pacific.” Nice one.

He chugs the first can of beer in one long gulp and opens the second. She could at least have pretended that it was kind of cute that he went to the effort, he thinks. It’s the thought that counts.

“Never again will I write a poem for a girl!”

Phirun grabs a pen and paper, then sits back down, drains his second beer and opens a third. He starts writing.

“Screw them,” he mumbles, still convinced of his poetic talent, “if

they

don’t like poems then I’ll write one for myself.”

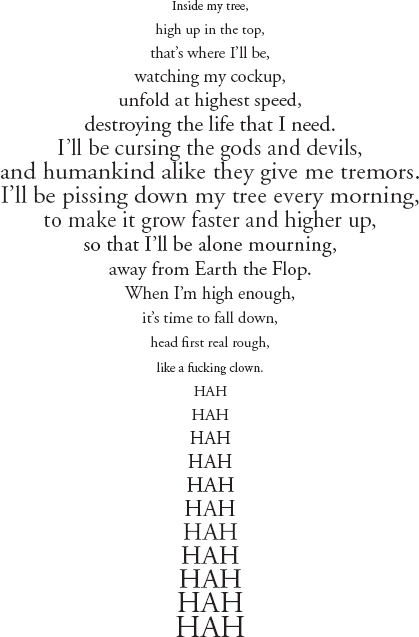

Twenty-six minutes and three beers later, he reads his outpouring. He didn’t have to amend anything — it had flown out of him in one fluent spurt. He stares a few seconds at his latest creation, then suddenly has an idea. He slowly rewrites it, centring every sentence in the middle of the page, making each line progressively bigger than its precedent, until he reaches the middle, when he begins to decrease the font size. At the end he adds a little extra. He looks at the result, satisfied:

Phirun sniggers — that’s exactly what I am, a fucking clown. He scribbles ‘Inside my tree without Merrilee’ on the top as title and signs his name with a flourish at the bottom.

“There,” he tells his empty kitchen. “I’m the new Rimbaud,” and finishes his last beer while a few drunken tears well up in his eyes.

SIXTEEN

TZAHALA HAS DONE her best to dress modestly. She’s wearing long, loose khaki-coloured travel pants and replaced her usual high-heeled shoes with flat, open

Clarks

sandals. Instead of a plunging neckline, a bland, round-collared t-shirt hanging a size too big is draped shapelessly over her shoulders. She wants to look like a tourist and avoid drawing attention, but her efforts prove futile.

When she enters The House, several heads turn in her direction. Half of them belong to excited men, the other half jealous women. There’s not much she can do about the attention, she seems to draw it no matter how badly she dresses. It usually only happens with foreign men, though, because she’s too dark-skinned for Cambodian tastes.

As is usual for a Saturday morning, The House is doing a busy trade. She walks straight through to the back, into a little open patio where it’s quieter. Tzahala finds herself a table for two. From where she sits she can hardly hear the music playing inside the main area, and the light buzz of the large electric fan above her head helps her relax. A girl donning staff uniform — a green polo shirt and dark trousers — approaches with a bright smile and places a complimentary glass of cold water down.

“What would you like to order, madam?” the girl enquires.

Tzahala considers a tempting chocolate croissant and espresso but eventually opts for a healthy fruit salad with yoghurt.

“And something to drink madam?”

“A lychee and mint cooler, thanks.”

The girl nods, smiles and disappears back inside. Tzahala takes a good look around, purposefully, trying to absorb every detail. Colonel Peeters has good taste, she thinks. The European style café is modern yet cosy, decorated with eye-catching local works of art. A fresh bunch of beautiful white

frangipani

flowers in a glass vase on top of the counter transmit their delicate perfume.

Her order arrives and Tzahala digs in, suddenly hungry. At another table in the corner a huge middle-aged foreign woman and a good-looking young Khmer man are having drinks. The large woman sports an explosion of blond hair on her head and is gobbling a chocolate mousse, while the young Khmer muscle factory conservatively sips a fruit juice. The woman is doing all the talking, her hand almost wringing the guy’s forearm, and Tzahala notices how the woman’s leg is also pressed against his. Sex tourism turning the tables on stereotypes, Tzahala thinks, half-fascinated. How democratic. She finishes her breakfast and grabs one of the free magazines lying about. ‘Asia Life Guide’, the title reads.

While she absentmindedly browses the magazine, her thoughts wander back to Colonel Peeters. She wants to send him a clear message that leaves no doubt about her determination to establish herself here. After all, this town is big enough for the both of them, surely. She’ll need to act as fiercely and ruthlessly as he does or he won’t take her seriously. There’s no escaping the element of a gamble, because if the Colonel

does

decide to launch a war, he might prove too much for her. But if her response makes the Colonel believe that she means business, then she’s got a chance he’ll give in.

Tzahala has made up her mind to take out one of his men, as a response to Driekamp. As it is written in the Torah: an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. The remaining, not inconsiderable questions are where, who and how? When she flicks over the page she stumbles upon a familiar sounding advertisement.

Home is where The House is

, she reads,

since 2003

. That makes sense, she thinks, that’s the year the Kimberley Agreement came into effect. It must have become too hot for him to sell his blood diamonds in Antwerp. She studies the advertisement with an amused smile. Once again, she admires the Colonel’s business savvy. He had probably set up The House as a front for his diamond activities, but he’s done it so well that it has become a profitable business in its own right.

Tzahala looks around. Even more people have entered now and she hears the ‘ting ting’ of the cash register repeatedly. The Colonel seems to take his little bakery seriously, she thinks. Tzahala motions at the passing waitress.

“Yes madam?”

“An espresso please.”

“One espresso? Yes madam!” she smiles and walks away.

Then Tzahala’s eyes alight upon an article.

The Chocolate House, by The House, opening soon

, the title reads. That’s right! One of her boys had mentioned it during an early morning call. Yet another of the Colonel’s smokescreen businesses, she thinks. Then an idea forms. Why not strike him there? He had attacked

her

network before she’d really started it up. She should respond in kind. Tit-for-tat, but there was a poetic justice to it, too. When the girl arrives with the espresso, Tzahala addresses her.

“What’s your name, honey?”

“My name is Bopha, madam!” the girl replies eagerly. Tzahala wonders if she unwittingly uttered some sort of code word, because suddenly she’s buried beneath a tidal wave of friendly questions.

“What’s your name, madam? Where you from? How long you stay Cambodia? Oh, you speak

Khmai!

Very good! You like my country? What you do? How old are you? You not fat! Are you married? Why not? ...”

Tzahala recognises her error. Cambodians, especially the younger generation, are famous for their questioning at foreigners. Most often simply because they are a friendly, welcoming people, projecting a genuine warmth of heart. Students are often eager to practise their English on any old foreign straggler with half a heartbeat. Tzahala interrupts while trying not to seem overly rude.

“Srei Bopha,”

she says, using the Khmer word for ‘miss’, “can I ask you a question?”

The girl is only too happy to oblige. “Of course madam, oh your

Khmai

very good!”

“I just read something about the new chocolate shop. This is part of The House, right? Is it open yet?”

“Yes, from The House. Same same, but different, only chocolate. It’s not open yet. Maybe next week. But now he has already started making chocolate, Mr Phirun from Belgium. He is all alone working inside every day, making many chocolates for the opening. I will become the new manager,” she proudly informs Tzahala.

“Congratulations, good for you! I look forward to trying some of your chocolates then.

Orkoun, Srei Bopha,”

she thanks the girl.

“Oh, you speak

Khmai! Meun ai they!”

the girl replies enthusiastically; Tzahala is most welcome.

Tzahala empties her espresso. She knows enough. That’s two questions answered, she thinks. First, where best to strike? The Colonel’s new chocolate venture. Second, who to strike? His chocolate maker and diamond delivery stooge. The waitress said this Phirun guy is Belgian, presumably a returnee — which reaffirms his connection with the Colonel’s organisation. This would be sweet, taking out his delivery boy will send a firm message to the Colonel, Tzahala muses. That leaves the third question remaining: how?

Tzahala looks around, trying to order the bill. At the table where the generously proportioned woman was just mauling her young Cambodian toy-boy, now sits a tall, muscular foreigner reading a newspaper. Tzahala cannot help checking him out a little longer than necessary. He must be in his late forties to early fifties, she estimates, but in great shape. He’s wearing black combat trousers and a plain white t-shirt. His biceps stretch the fabric of his short sleeves most agreeably, and his light brown, almost blond hair cascades into a wild fringe. His features are rough and square, giving him an authoritative air. This is what a general should look like, she thinks, apart from his uncombed hair. Tzahala goes for mature, masculine types and all of a sudden she’s struggling to remember the last time she had sex.

When the man eventually looks up, Tzahala quickly averts her eyes. She feels caught out — usually it’s the other way around, with her catching men ogling her. Business first. She summons herself and reconsiders the third conundrum: how to dispose of this Phirun guy? It shouldn’t be difficult, in any case. I could ask my agent to hire a local contract killer to do the job. Walk in, shoot the guy, walk out. Quickly and clinically and with the minimum of fuss. None of the customary, over-emotional acid throwing or axe-wielding mess. The waitress had said that he works there every day, alone. That should make it a quick and easy hit.