Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (119 page)

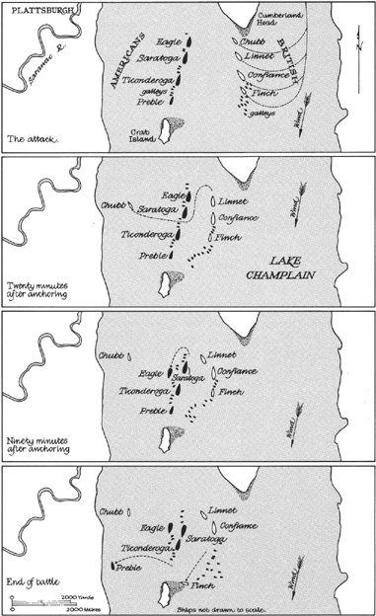

This last-minute scramble means that there will be no time for a shakedown cruise. The big frigate will go into action with a strange crew who have scarcely had a chance to fire her guns or hoist her sails. Yet it could all have been avoided if Sir James Yeo—or Prevost—had not been obsessed with the shipbuilding war on Lake Ontario. Not until Macdonough’s

Saratoga

appeared on the lake in late May did the British commanders wake up to their peril. Now they are paying for their inattention.

Downie shares his disgust over Prevost’s letter with his second-in-command, Captain Daniel Pring, whom he has just replaced as senior commander on the lake.

“I will not write any more letters,” he declares to Pring. “This letter does not deserve an answer but I will convince him that the naval force will not be backward in their share of the attack.”

In short, goaded by Prevost, he will not wait for the enemy to emerge from the safe harbour at Plattsburgh to meet him on the open lake. He will chance a direct bows-on attack against Macdonough’s anchored fleet.

Downie is prepared to attempt this dangerous action only because Prevost has told him that he will launch his land assault at the same time. Once the shore batteries have been stormed and taken, Downie believes, Macdonough will be in peril. With the captured guns turned on him he will have to quit his anchorage and, during the confusion, the British will have the advantage.

At midnight, the wind switches to the northeast. Downie weighs

anchor, and the fleet slips southward toward Plattsburgh Bay carrying one thousand men, including the riggers and outfitters still straining to complete their work.

At five, the fleet reaches Cumberland Head. Here Downie scales his guns—clears out the bores, which have never been fired, with blank cartridges. This is the signal, pre-arranged with Prevost, to announce his arrival and to co-ordinate a simultaneous attack by the land forces.

In the hazy dawn, Downie boards his gig, nudges it around the point, and examines the American fleet through his glass.

Macdonough’s four large vessels are strung out in line across the bay, with the gunboats in support—the twenty-gun brig

Eagle

at the northernmost end, followed by the larger

Saratoga

, twenty-six guns, the schooner

Ticonderoga

, seven guns, and the sloop

Preble

, seven guns, at the rear. With twenty-seven long cannon and ten heavy carronades, Downie’s

Confiance

is more than a match for Macdonough’s flagship. On the other hand, the combined batteries of

Saratoga

and

Eagle

can hurl a heavier weight of metal than can Downie’s two largest vessels,

Confiance

and

Linnet

, the latter a brig of sixteen guns under Captain Pring.

With this in mind, Downie plans his attack.

Confiance

will take on the American flagship

Saratoga

, first passing

Eagle

and delivering a broadside, then turning hard a-port to anchor directly across the bows of Macdonough’s ship.

Linnet

, supported by the sloop

Chubb

, will engage

Eagle

. In this way the two largest American vessels will be under fire from three of the British. The fourth and smallest British vessel, the sloop

Finch

, and eleven gunboats will hit the American rear, boarding the former steamer

Ticonderoga

and at the same time attacking the little

Preble

.

Back on his flagship, Downie calls his officers to a conference, outlines his strategy, and speaks a few words of encouragement to the ship’s company:

“Now, my lads, there are the American ships and batteries. At the same moment we attack the ships our army are to storm the batteries. And, mind, don’t let us be behind.”

They answer with a cheer.

At almost the same time, Macdonough’s men kneel on the deck of

Saratoga

as their commander reads a short prayer:

“Thou givest not always the battle to the strong, but canst save by many or by few—hear us, Thy poor servants, imploring Thy help that Thou wouldst be a defence unto us against the face of the enemy. Make it clear that Thou art our Saviour and Mighty Deliverer, through Jesus Christ, our Lord.”

From the mast of the flagship, Macdonough’s signal reminds his men why they are fighting:

Impressed seamen call on every man to do his duty

.

In that message there is unconscious irony. It is well that Macdonough is not a party to the peace talks at Ghent where both the British and American negotiators have already decided to toss the whole bitter matter of impressment into the dustbin.

As the British fleet turns into line abreast, a silence falls over the bay. It is not broken until the ships come within range.

Eagle

hurls the first shot at Downie’s

Confiance

, which has moved into the van. The ball splashes well short of its objective.

Linnet

, passing the American flagship en route to its target, fires a broadside that does little damage except to shatter a crate containing a fighting gamecock. The rooster flies into the rigging, crowing wildly, a touch of bravado that raises a cheer from

Saratoga

’s crew.

Downie, gazing anxiously at the headland, wonders to James Robertson, his First Officer, why Prevost has not commenced his attack. On

Saratoga

, Macdonough personally sights a long twenty-four and fires the first shot at his opponent’s flagship. The heavy ball strikes the tall frigate near the hawse hole and tears its way the full length of the deck, killing and wounding several of Downie’s crew and demolishing the wheel.

Now the action becomes general. Grey smoke pours from the guns, cannonballs ricochet across the glassy waters of the bay, chain-shot tears through the rigging. Through this maelstrom,

Confiance

sails toward her objective, sheets tattered, hawsers shredded, two anchors shot away. But the wind is erratic, and Downie

realizes he cannot cross the head of the American line as he had hoped. He is forced to anchor more than three hundred yards from Macdonough’s

Saratoga

—a manoeuvre he executes with great coolness under the other’s hammering fire—but in doing so he loses two port anchors and fouls the kedge anchors at his stern. That will cost

Confiance

dear.

Downie’s guns have not yet fired. His long twenty-fours have been carefully wedged with quoins for point-blank fire and double-shotted for maximum effect. Now, at a signal, a sheet of flame erupts from the British flagship, and more than seven hundred pounds of cast iron strike

Saratoga

. The effect is terrible. The American frigate shivers from round top to hull, as if from a violent attack of ague. Macdonough sees half his crew hurled flat on the deck. Forty are killed or wounded; the scuppers are running with blood. The Commodore’s right-hand man, Lieutenant Peter Gamble, is among the dead, killed instantly while on his knees, sighting the bow gun.

Saratoga

replies to

Confiance

, broadside for broadside. As George Downie stands behind one of his long twenty-fours, commanding the action, an enemy ball strikes the muzzle, knocking the gun off its carriage and thrusting it back into the commander’s midriff. Downie falls dead, his watch flattened, his skin unbroken. For the British, it is a critical loss.

Linnet

and

Chubb

have moved up to support

Confiance

in her battle with the two big American vessels. But a series of withering broadsides from

Eagle

so badly cripples

Chubb

that with half her crew casualties, her sails in tatters, her boom shaft and halyards wrecked, her hammock netting ablaze, her commander wounded, and only six men left on deck, she drifts helplessly and finally strikes her colours.

At the end of the line,

Finch

and the British gunboats are attacking the schooner

Ticonderoga

and the little sloop

Preble

. The latter wilts under the onslaught, cuts her cable, and drifts out of action. But only four of the British gunboats remain to do battle. The rest flee the action, their militia crews cowering in the bottoms under a shower of grape and musket fire, while the commander of the flotilla bolts to the hospital tender, remaining there until the end of the battle, eventually evading court martial only by escaping while en route to trial.

The Battle of Lake Champlain

Ticonderoga

wards off

Finch

, which is raking her from the stern, but is herself in trouble, taking water, her pumps struggling to keep up with the inflow.

Finch’s

commander, Lieutenant William Hicks,

brandishing a cutlass to bring the terrified pilot into line, tries to wear the British sloop in the light erratic wind and finds himself stuck fast on a reef near Crab Island, where he fights a brief engagement with the invalids manning their six-pounders. He, too, is out of action.

The four remaining British gunboats, sweeps thrashing the water, come within a boathook of

Ticonderoga

. Her commander, Lieutenant Stephen Cassin, a commodore’s son, coolly walks the taffrail amid a shower of shot, directing his men to ward off the boarders. His second-in-command is cut in two by a cannonball and hurled into the lake. A sixteen-year-old midshipman, Hiram Paulding—a future rear-admiral—mans the guns, finds the slow match useless, and repeats Barclay’s action on Erie by discharging his pistol into the powder holes. In between the cannon blasts he continues to fire the pistol at the British, still vainly trying to scramble aboard.

But the main battle is at the head of the line between the American

Saratoga

and

Eagle

and the British

Confiance

and

Linnet. Eagle

, with most of her starboard guns rendered useless, cuts her cable and changes position to bring her port broadside into action. In doing so she positions herself to threaten

Confiance

but leaves Macdonough’s flagship exposed to

Linnet

’s raking broadsides.

Linnet

’s cannons batter

Saratoga

’s long guns into silence. All but one of Macdonough’s carronades have been dismounted in the action or wrecked by overzealous crews who overload in the absence of experienced officers. Hardly a man on either flagship has escaped injury. Macdonough is lucky. As he bends over a gun to sight it, a spanker boom, sliced in two by cannon fire, knocks him briefly insensible. A little later he suffers a grislier mishap: the head of his gun captain, torn off by British round-shot, comes hurtling across the deck, strikes him in the midriff, knocking him into the scuppers. He is winded but unharmed.

Now the naval bolt on

Saratoga

’s last carronade breaks, throwing the heavy gun off its carriage and hurling it down the hatch. Macdonough is in trouble. He has no guns left on the starboard side and only one officer. In most situations this would be enough

to force him to strike his colours, but Macdonough has prepared for such an emergency. He turns to the complicated series of spring cables, hawsers, and kedge anchors that will allow him to wind his ship: to swing it end for end so that he can bring the seventeen guns on his port side—none of which has been fired—to bear upon his opponent.

It is a difficult and awkward manoeuvre, requiring careful timing and skill—a knowledge of when to raise one anchor, when to drop another. Now it must be done under the hazard of enemy fire.

Fortunately that fire has slackened, for the British ships too are in a bad way, and the guns of

Confiance

are firing too high. The seamen, new to the frigate, to each other, and to their officers, have had no gun drill. The cannon have been set for point-blank range, but at each blast they leap up on their carriages. The quoins, which are supposed to wedge them in place, are loosened, causing the muzzles to edge up. As a result, more damage is done to hammocks, halyards, spars, and pine trees on the shore than to the opposing vessels.

Macdonough manages to wind his ship half-way round until she is at right angles to her former position. There she sticks, stern facing

Linnet

’s broadside. The British brig rakes the battered American flagship and the line of sweating seamen straining at the hawser. A splinter strikes the Commodore’s sailing master, Peter Brum, as he runs forward to oversee the manoeuvre. It slices through his uniform, barely touching the skin but stripping him of his clothing. Naked, he continues his task.

Slowly, Brum and Macdonough get the ship turning again until the first of her portside carronades comes into play against

Confiance

. The gun crews go to work as the frigate continues her half circle and, one by one, the heavy guns open fire.

On

Confiance

, Downie’s young successor, James Robertson, is attempting the same manoeuvre but with less success. His frigate is in terrible shape, her masts like bunches of matches, her sails like bundles of rags, her rigging, spars, and hull shattered. Almost half her crew are out of action. The wife of the flagship’s steward, in the act of binding a wounded seaman’s leg, is struck by a ball that tears

through the side of the ship, carries away her breasts, and flings her corpse across the vessel. One of Nelson’s veterans aboard

Confiance

is heard to remark that compared to this action, Trafalgar was a mere fleabite. The ship’s carpenter has already plugged sixteen holes below the waterline, but a great seven-foot gash in her hull, where a plank has been torn away, cannot be mended. To keep her from sinking it has been necessary to run in all the guns on the port side—most are useless anyway—and double shot those on the starboard to keep the holes above the water.