Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (18 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

He determines to get the news as swiftly as possible to his Canadian partners in the South West Company. It does not occur to him that this may be seen as an act approaching treason any more than it occurs to him that his news will travel faster than the official dispatches. The South West Company is owned jointly by Astor and a group of Montreal fur “pedlars,” which includes the powerful North West Company. Astor engages in a flurry of letter writing to his agents and partners. Thus the British are apprised of the war before the Americans on the frontier, including General Hull en route to Detroit and Lieutenant Hanks at Michilimackinac, realize it. Brock gets the news on June 26 and immediately dispatches a letter to Roberts at St. Joseph’s Island. But a South West Company agent, Toussaint Pothier, based at Amherstburg, has already had a direct communication from Astor. Pothier alerts the garrison, leaps into a canoe, and paddles off at top speed. He beaches his canoe at St. Joseph’s on July 3.

Roberts puts his men and Indians on the alert. Lewis Crawford, another South West employee, organizes 140 volunteer voyageurs.

A twelve-day interval of frustration follows. Brock’s message, which arrives by canoe on July 8, simply advises that the war is on and that Roberts should act accordingly. Roberts requisitions stores and ammunition from the South West Company (the very stores that concern John Jacob Astor, who will, of course, be paid for them), takes over the North West Company’s gunboat

Caledonia

, impresses her crew, and sends off a message by express canoe to the North West Company’s post at Fort William, asking for reinforcements.

Just as he is preparing to attack Mackinac, a second express message arrives from Brock on July 12. The impetuous general has had his enthusiasm curbed by his more cautious superior, Sir George Prevost. The Governor General is hoping against hope that the reports of war are premature, that the Americans have come to their senses, that a change of heart, a weakness in resolve, an armistice—anything—is possible. He will not prejudice the slightest chance of peace. Brock orders Roberts to hold still, wait for further orders. The perplexed captain knows he cannot hold the Indians for long—cannot, in fact, afford to. By night they chant war songs, by day they devour his dwindling stock of provisions.

Then, on July 15, to Roberts’s immense relief, another dispatch arrives from Brock which, though equivocal, allows him to act. The Major-General, with an ear tuned to Sir George’s cautionary instructions and an eye fastened on the deteriorating situation on the border, tells Roberts to “adopt the most prudent measures either of offense or defense which circumstances might point out.” Roberts resolves to make the most of these ambiguous instructions. The following morning at ten, to the skirl of fife and the roll of drum-banners waving, Indians whooping—his polyglot army embarks upon the glassy waters of the lake.

Off sails

Caledonia

loaded with two brass cannon, her decks bright with the red tunics of the regulars. Behind her follow ten bateaux or “Mackinac boats” crammed with one hundred and eighty voyageurs, brilliant in their sashes, silk kerchiefs, and capotes. Slipping in and out of the flotilla are seventy painted birchbark canoes containing close to three hundred tribesmen—Dickson, in Indian dress, with

his fifty feathered Sioux; their one-time enemies, the Chippewa, with coal-black faces, shaved heads, and bodies daubed with pipe clay; two dozen Winnebago, including the celebrated one-eyed chief, Big Canoe; forty Menominee under their head chief, Tomah; and thirty Ottawa led by Amable Chevalier, the half-white trader whom they recognize as leader.

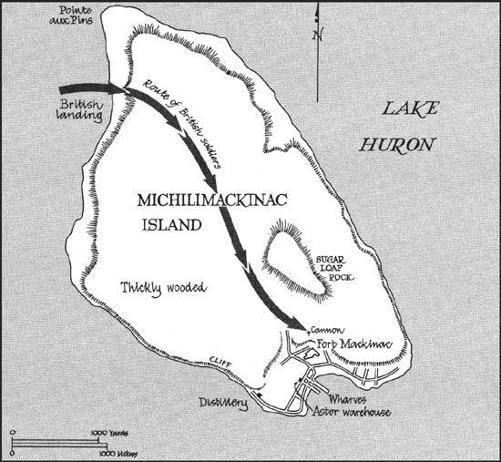

Ahead lies Mackinac Island, shaped like an aboriginal arrowhead, almost entirely surrounded by 150-foot cliffs of soft grey limestone. The British abandoned it grudgingly following the Revolution, realizing its strategic importance, which is far more significant than that of St. Joseph’s. Control of Mackinac means control of the western fur trade. No wonder Roberts has no trouble conscripting the Canadian voyageurs!

They are pulling on their oars like madmen, for they must reach their objective well before dawn. Around midnight, about fifteen miles from the island a birchbark canoe is spotted. Its passenger is an old crony from Mackinac, a Pennsylvania fur trader named Michael Dousman. He has been sent by Hanks, the American commander, to try to find out what is taking place north of the border. Dousman, in spite of the fact that he is an American militia commander, is first and foremost a fur trader, an agent of the South West Company, and an old colleague and occasional partner of the leaders of the voyageurs and Indians. He greets Dickson, Pothier, Askin, and Crawford as old friends and cheerfully tells Roberts everything he needs to know: the strength of the American garrison, its armament (or lack of it), and—most important of all—the fact that no one on the island has been told that America is at war.

Dousman’s and Roberts’s concerns are identical. In the event of a struggle, they want to protect the civilians on the island from the wrath of the Indians. Dousman agrees to wake the village quietly and to herd everybody into the old distillery at the end of town where they can be guarded by a detachment of regulars. He promises not to warn the garrison.

At three that morning, the British land at a small beach facing the only break in the escarpment at the north end of the island. With

the help of Dousman’s ox team the voyageurs manage to drag the two six-pounders over boulders and through thickets up to the 300-foot crest that overlooks the fort at the southern tip. Meanwhile, Dousman tiptoes from door to door wakening the inhabitants. He silently herds them to safety, then confronts the bewildered Lieutenant Hanks, who has no course but surrender. The first objective in Brock’s carefully programmed campaign to frustrate invasion has been taken without firing a shot.

“It is a circumstance I believe without precedent,” Roberts reports to Brock. For the Indians’ white leaders he has special praise: their influence with the tribes is such that “as soon as they heard the Capitulation was signed they all returned to their Canoes, and not one drop either of Man’s or Animal’s blood was Spilt.…”

Askin is convinced that Hanks’s bloodless surrender has prevented an Indian massacre: “It was a fortunate circumstance that

the Fort Capitulated without firing a Single Gun, for had they done so, I firmly believe not a Soul of them would have been Saved.… I never saw so determined a Set of people as the Chippewas & Ottawas were. Since the Capitulation they have not drunk a single drop of Liquor, nor even killed a fowl belonging to any person (a thing never known before) for they generally destroy every thing they meet with.”

Michilimackinac Island

Dickson’s Indians feel cheated out of a fight and complain to the Red-Haired Man, who keeps them firmly under control, explaining that the Americans cannot be killed once they have surrendered. To mollify them, he turns loose a number of cattle, which the Sacs and Foxes chase about the island until the bellowing animals, their flanks bristling with arrows, hurl themselves into the water.

They are further mollified by a distribution of blankets, provisions, and guns taken from the American commissariat, which also contains tons of pork and flour, a vast quantity of vinegar, soap, candles, and—to the delight of everybody–357 gallons of high wines and 253 gallons of whiskey, enough to get every man, white and red, so drunk that had an enemy force appeared on the lake, it might easily have recaptured the island.

These spoils are augmented by a trove of government-owned furs, bringing the total value of captured goods to £10,000, all of it to be distributed, according to custom, among the regulars and volunteers who captured the fort. Every private soldier will eventually receive ten pounds sterling as his share of the prize money, officers considerably more.

The message to the Indians is clear: America is a weak nation and there are rewards to be gained in fighting for the British. The fall of Mackinac gives the British the entire control of the tribes of the Old Northwest.

Porter Hanks and his men are sent off to Detroit under parole: they give their word not to take any further part in the war until they are exchanged for British or Canadian soldiers of equivalent rank captured by the Americans—a device used throughout the conflict to obviate the need for large camps of prisoners fed and clothed at

the enemy’s expense. The Americans who remain on the island are obliged to take an oath of allegiance to the Crown; otherwise they must return to American territory. Most find it easy to switch sides. They have done it before; a good many were originally British until the island changed hands in 1796.

Curiously, one man is allowed to remain without taking the oath. This is Michael Dousman, Hanks’s spy and Roberts’s prisoner. Dousman is given surprising leeway for an enemy, being permitted to make business trips to Montreal on the promise that he will not travel through U.S. territory. He is required to post a bond for this purpose but has no trouble raising the money from two prominent Montreal merchants.

Dousman’s business in Montreal is almost certainly John Jacob Astor’s business. All of Astor’s furs are now in enemy territory. But the South West Company is still a multinational enterprise, and Astor has friends in high positions in both countries. Through his Montreal partners he manages to get a passport into Canada. In July he is in Montreal making arrangements for his furs to be forwarded from Mackinac Island (which has not yet fallen). These furs are protected in the articles of capitulation; over the next several months, bales of them arrive in Montreal from Mackinac. Astor’s political friends in Washington have alerted the customs inspectors at the border points to pass the furs through, war or no war. Over the next year and a half, the bullet-headed fur magnate manages to get his agents into Canada and to bring shipment after shipment of furs out to the New York market. A single consignment is worth $50,000, and there are many such consignments. For John Jacob Astor and the South West Company, the border has little meaning, and the war is not much more than a nuisance.

FOUR

Detroit

The Disintegration of William Hull

Those Yankee hearts began to ache

,

Their blood it did run cold

,

To see us marching forward

So courageous and so bold

.

Their general sent a flag to us

,

For quarter he did call

,

Saying, “Stay your hand, brave British boys

,

I fear you’ll slay us all.”

—From “Come All Ye Bold Canadians,”

a campfire ballad of the War of 1812.

ABOARD THE SCHOONER

Cuyahoga Packet

, entering Lake Erie, July 2, 1812. William K. Beall, assistant quartermaster general in William Hull’s Army of the Northwest, stretches out on deck, admiring the view, ignorant of the fact that his country has been at war for a fortnight and the vessel will shortly be entering enemy waters.

Beall counts himself lucky. He reclines at his ease while the rest

of Hull’s tattered army trudges doggedly toward Detroit, spurred on by Eustis’s order to move “with all possible speed.” Thanks to the

Cuyahoga’s

fortuitous presence at the foot of the Maumee rapids, Hull has been able to relieve his exhausted teams. The schooner is loaded with excess military stores—uniforms, band instruments, entrenching tools, personal luggage—and some thirty sick officers and men, together with three women who have somehow managed to keep up with their husbands on the long trek north.

It is a foolhardy undertaking. War is clearly imminent, even though Eustis, the bumbling secretary, gave no hint of it in his instructions to the General. Hull’s own officers have pointed out that the

Cuyahoga

must pass under the British guns at Fort Amherstburg, guarding the narrow river boundary, before she can reach Detroit; but their commander, sublimely unaware of his country’s declaration, remains confident that she will get there before the army.