Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (25 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Hull suggests, hesitantly, that the army might be well advised to withdraw as far as the Maumee. Cass retorts that if he does that, every man in the Ohio militia will leave him. That puts an end to it: the army will withdraw across the river to Detroit, but no farther.

Lewis Cass is beside himself. In his eyes, Hull’s decision is both fatal and unaccountable; he cannot fathom it. Coming after a series of timid, irresolute, and indecisive measures, this final about-face has dispirited the troops and destroyed the last vestige of confidence they may have had in their commander. Cass is undoubtedly right; far better if Hull had never crossed the river in the first

place—at least until his supply lines were secure. A sense of astonishment, mingled with a feeling of disgrace, ripples through the camp. Robert Lucas feels it: the orders to cross the river under cover of darkness are, he thinks, especially dastardly. But cross the army must, and when night falls the men slink into their boats. By the following morning there is scarcely an American soldier left on Canadian soil.

WHILE BROCK IS ADVANCING

toward the Detroit frontier, intent on attack, his superior, Sir George Prevost, is doing his best to wind down the war. He informs Lord Liverpool that although his policy of conciliation has not prevented hostilities, he is determined to do nothing to exacerbate the situation by aggressive action:

“… Your Lordship may rest assured that unless the safety of the Provinces entrusted to my charge should require them, no measures shall be adopted by me to impede a speedy return to those accustomed relations of amity and goodwill which it is the mutual interest of both countries to cherish and preserve.”

Sir George, who has never believed in the reality of the war, is now convinced it will reach a swift conclusion. Augustus Foster has written from Halifax, en route home from Washington, with the news that Britain has revoked the hated Orders in Council. American ships may now trade with continental Europe without fear of seizure. Madison in June made it clear that the Orders were America’s chief reason for going to war. Surely, then, with Britain backing off, he will come to his senses and halt the invasion.

Sir George sees no reason to wait for the President. Why not suspend hostilities at once—at least temporarily? Why spill blood senselessly if the war is, in effect, over?

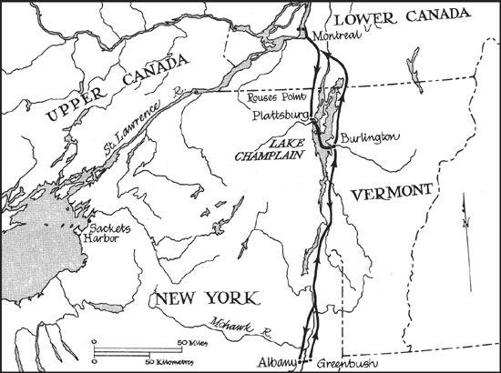

On August 2, he dispatches his aide, Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Baynes, with a flag of truce to treat with Major-General Henry Dearborn, the U.S. commander, at his headquarters at Greenbush, across the river from Albany, New York.

The American in charge of the overall prosecution of the war in the north has not seen military service for two decades. A ponderous, flabby figure, weighing two hundred and fifty pounds, with a face to match, Dearborn does not look like a general, nor does he act like one. He is a tired sixty-one. His soldiers call him Granny.

His reputation, like Hull’s, rests on the memory of another time. As a Revolutionary major he fought at Bunker Hill, then struggled, feverish and half-starved, with Arnold through the wintry forests of Maine to attack Quebec, was captured and exchanged to fight again—against Burgoyne at Saratoga, at Monmouth Court House in ’78, with General John Sullivan against the Indians in ’79, at Yorktown in ’81. A successful and influential Massachusetts politician in the post-war era, Secretary of War for eight years in Jefferson’s cabinet, he is now an old soldier who was slowly fading away in his political sinecure until the call to arms restored him to command.

The American strategy, to attack Canada simultaneously at Detroit, Niagara, Kingston, and Montreal, is faltering. Given the lack of men and supplies it is hardly likely that these thrusts can occur together. It is assumed, without anybody quite saying so, that Dearborn will co-ordinate them, but General Dearborn does not appear to understand.

Strategically, the major attack ought to be made upon Montreal. A lightning thrust would sever the water connection between the Canadas, deprive the upper province of supplies and reinforcements, and, in the end, cause it to wither away and surrender without a fight. The problem is that the New Englanders, whose co-operation is essential, do not want to fight, while the southerners and westerners in Kentucky, Tennessee, South Carolina, and Ohio are eager for battle. There is also the necessity of securing America’s western flank from the menace of the Indians. Thus, the American command pins its initial hopes on Hull’s army while the forces on Lake Champlain remain stagnant.

To describe Dearborn’s prosecution of the war as leisurely is to understate that officer’s proclivity for sluggish movement. He has spent three months in New England, attempting in his bumbling

fashion to stir the people to belligerence with scarcely any success. The governors of Massachusetts and Connecticut are particularly obdurate. When Dearborn asks Caleb Strong to call out fourteen companies of artillery and twenty-seven of infantry for the defence of his Massachusetts ports and harbours, Governor Strong declares that the seacoast does not need defending since the government of Nova Scotia has “by proclamation, forbid[den] any incursions or depredations upon our territories.” Governor John Cotton Smith of Connecticut points out that the Constitution “has ordained that Congress may provide for calling forth the militia

to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions.”

Since there has been neither insurrection nor invasion, he argues, no such emergency exists. Of course, Governor Smith adds, the militia stands ready to repel any invasion should one take place. Clearly, he believes that will never happen.

Dearborn dawdles. Eustis tries to prod him into returning to his base at Albany to get on with the invasion of Canada, but Eustis is not much of a prodder. “Being possessed of a full view of the intentions of government,” he starts out—then adds a phrase scarcely calculated to propel a man of Dearborn’s temperament into action; “take your time,” he finishes, and Dearborn does just that.

It is an odd coincidence that the Secretary of War and his predecessor, Dearborn, are both medical men, former physicians trained to caution, sceptical of haste, wary of precipitate moves that might cause a patient’s death. One of Dearborn’s tasks is to create diversions at Kingston and at Niagara to take the pressure off Hull; but when Hull crosses the Detroit River, Dearborn is still in Boston. “I begin to feel that I may be censured for not moving,” he remarks in what must be the understatement of the war, but he doubts the wisdom of leaving. To which Eustis responds: “Go to Albany or the Lake. The troops shall come to you as fast as the season will admit, and the blow must be struck. Congress must not meet without a victory to announce to them.” Dearborn ponders this for a week before making up his mind, then finally sets off, reaching Greenbush on July 26, where some twelve hundred unorganized troops await him.

His letters to Washington betray his indecision (“I have been in a very unpleasant situation, being at a loss to determine whether or not I ought to leave the seacoast”). He is woefully out of touch with his command, has no idea who runs his commissary and ordnance departments, is not even sure how far his authority extends, although this has been spelled out for him. In a remarkable letter he asks Eustis: “Who is to have command of the operations in Upper Canada? I take it for granted that my command does not extend to that distant quarter.” These are the words of a man trying to wriggle out of responsibility, a man for whom the only secure action is no action at all. He has been ordered to keep the British occupied while Hull advances. But he does nothing.

This, then, is the character of the commander who is to receive an offer of truce brought to his headquarters by the personable Lieutenant-Colonel Baynes.

It takes Baynes six days to reach Albany from Montreal. An experienced officer with thirty years’ service behind him, he keeps his eyes open, recording, in the pigeon-holes of his mind, troop dispositions, the state of preparedness of soldiers, the morale of the countryside. At Plattsburg he is greeted cordially by the ranking major-general, a fanner named Moore, who gets him a room at the inn. Baynes notes that the militia have no uniforms, the only distinguishing badge being a cockade in their hats, and that they do not appear to have made any progress in the first rudiments of military drill. All the officers at Plattsburg express approval of Baynes’s mission and one of them, a Major Clarke, is ordered to accompany him by boat to Burlington near the southern end of Lake Champlain. From this point on Baynes proceeds with more difficulty; the commander at Burlington is not enchanted by the spectacle of an enemy officer coolly looking over his force. But Baynes finally persuades him to let him proceed to Albany, 150 miles to the south.

For Lieutenant-Colonel Baynes the journey is salutary. He fails to see any military preparation but forms a strong opinion of the mood of the people, which he reports to Prevost:

Baynes’s Journey to Albany

“My appearance travelling thro’ the country in uniform excited very great curiosity and anxiety. The Inns where the coach stopt were instantly crowded with the curious and inquisitive. I did not hear a single individual express a wish but for the speedy accommodation of existing differences and deprecating the war, in several instances these statements were expressed in strong and violent language and on Major Clarke endeavouring to check it, it produced a contrary effect. The universal sentiment of this part of the country appears decidedly adverse to war. I experienced everywhere respect and attention.”

On the evening of August 8, Baynes reaches Albany and goes immediately to Dearborn’s headquarters at nearby Greenbush. The American commander receives him with great affability, says he personally wants an armistice on honourable terms, and admits that “the burden of command at his time of life was not a desirable charge.” Baynes finds him in good health but shrewdly concludes that he “does not appear to possess the energy of mind or activity of body requisite for the important station he fills.”

An agreement of sorts is quickly concluded. Dearborn explains that his instructions do not allow him to sign an armistice, but he can issue orders for a temporary cessation of hostilities. The two men agree that should Washington countermand this order, four days’ notice will be given before hostilities are resumed. Under this arrangement, the troops will act only on the defensive until a final decision is reached. To Dearborn, the procrastinator, this agreement has the great advantage of allowing him to recruit his forces and build up his supplies without fear of attack. “It is mutually understood that … no obstructions are to be attempted, on either side, to the passage of stores, to the frontier posts.”

And Hull, who is desperate for both supplies and men? Hull is not included, specifically at Dearborn’s request: “I could not include General Hull … he having received his orders directly from the department of war.”

Thus is concluded a kind of truce, in which both sides are allowed to prepare for battle without actually engaging in one.

These arrangements completed, Lieutenant-Colonel Baynes prepares to take his leave. There is a brief altercation over the use of Indians in the war. Dearborn, in strong language, attacks the British for using native warriors, implying that the Americans are free from reproach in this area. Baynes retorts that Hull’s captured dispatches make it clear that he has been doing his best to persuade the Indians to fight for the Americans. That ends the argument. But Baynes has misread Hull’s intentions. At Madison’s insistence, the Americans use the Indians as scouts only. Hull’s efforts have been designed only to keep the Indians neutral.

With great difficulty, Baynes convinces Dearborn to allow him to return to Montreal by a different route along the eastern shores of Lake Champlain; it allows him to size up American strength and assess the mood of the New Englanders.

The little coach clip-clops its way through Vermont’s beguiling scenery, rattling down crooked clay roads and over rustic bridges, past stone mills perched above gurgling rivers, through neat, shaded villages hugging the sloping shoreline—a peaceful, pastoral land of

farms, wayside inns, and the occasional classical courthouse, as yet untouched by battle. The war seems very far away and, Baynes notes, the people almost totally unprepared. The militia do not impress him.