Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (34 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

“One thing I can with great truth say; nothing but General Stephen Van Rensselaer’s having the command of this campaign could have saved the service from confusion; the State from disgrace, and the cause from perdition; and nothing could have been more fortunate for the General than the man he has at his elbow, for Solomon

in fact

and

truth

does know everything which appertains to the economy of a camp—Stop:—Away we must all march, at beat of drum, and hear an old Irish clergyman preach to us, Amen. I have become a perfect machine; go just where I’m ordered.”

LEWISTON, NEW YORK, AUGUST

16, 1812. Consternation in the American camp! Excitement—then relief. A red-coated British officer gallops through, carrying a flag of truce. Hull may be in trouble on the Detroit frontier. (He is, at this very moment, signing the articles of surrender.) But here on the Niagara the danger of a British attack, which all have feared, is over.

Major John Lovett cannot contain his delight at this unexpected reprieve. “Huzza! Huzza!” he writes in his journal, “… an Express from the Governor General of Canada to Gen. Dearborn proposing an Armistice!!!!” The news is so astonishing, so cheering, that he slashes four exclamation marks against it.

The following night, at midnight, there is a further hullabaloo as more riders gallop in from Albany bearing letters from Dearborn “enclosing a sort of three legged armistice between some sort of an Adjutant General on behalf of the governor general of Canada and the said Gen. Dearborn.” Now the camp is in a ferment as messages crisscross the river: “There is nothing but flag after flag, letter after letter.”

A truce, however brief, will allow the Americans to buy time, desperately needed, and to reinforce the Niagara frontier, desperately

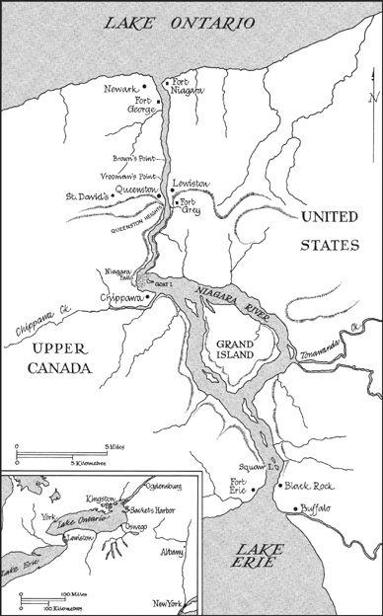

undermanned, that stretches thirty-six miles along the river that cuts through the neck of land separating Lake Erie from Lake Ontario. At the southern end, the British Fort Erie faces the two American towns of Buffalo, a lively village of five hundred, and its trading rival, Black Rock. At the northern end, Fort George on the British side and Fort Niagara on the American bristle at each other across the entrance into Lake Ontario. The great falls, whose thunder can be heard for miles, lie at midpoint. Below the gorge that cuts through the Niagara escarpment are the hamlet of Lewiston, on the American side, where Van Rensselaer’s army is quartered, and the Canadian village of Queenston, a partially fortified community, overshadowed physically by the heights to the south and economically by the village of Newark (later Niagara-on-the-Lake) on the outskirts of Fort George.

At Lewiston, the river can be crossed in ten minutes, and a musket ball fired from one village to the other still has the power to kill. For some time the Americans have been convinced that the British mean to attack across the river. It is widely believed that they have three thousand men in the field and another thousand on call. As is so often the case in war, both sides overestimate the forces opposite them; Brock has only four hundred regulars and eight hundred militia, most of the latter having returned to their harvest.

New York State is totally unprepared for war. The arms are of varying calibres; no single cartridge will suit them. Few bayonets are available. When Governor Tompkins tries to get supplies for the militia from the regular army, he is frustrated by red tape. From Bloomfield comes word from one general that “if Gen. Brock should attack … a single hour would expend all our ammunition.” From Brownville, another general reports that the inhabitants of the St. Lawrence colony are fleeing south. From Buffalo, Peter B. Porter describes a state bordering on anarchy—alarm, panic, distrust of officers, military unpreparedness. If Hull is beaten at Detroit only a miracle can save Van Rensselaer’s forces from ignoble defeat.

Now, when least expected, the miracle has happened and the army has been given breathing space.

The Niagara Frontier

Lieutenant-Colonel Solomon Van Rensselaer, the old campaigner, immediately grasps the significance of the projected armistice, but he faces serious problems. All the heavy cannon and supplies he needs are far away at Oswego at the eastern end of Lake Ontario. The roads are mired; supplies can only be moved by water. At present the British control the lake, but perhaps the terms of the truce can be broadened to give the Americans an advantage.

The agreement with Dearborn is specific: the British will not allow any facility for moving men and supplies that did not exist before it was signed. In short, the Americans cannot use the lake as a common highway. Solomon is determined to force his enemies to give way; the security of the Army of the Centre depends upon it.

He goes straight to his cousin, the General.

“Our situation,” he reminds him, “is critical and embarrassing,

something

must be done, we must have cannon and military stores from Oswego. I shall make a powerful effort to procure the use of the waters, and I shall take such ground as will make it impossible for me to recede. If I do not succeed, then Lovett must cross over and carry Gen. Dearborn’s orders into effect.”

“Van,” says Lovett, “you may as well give that up, you will not succeed.”

“If I do not,” retorts his friend, “it will not be my fault.”

He dons full military dress and crosses to the British fort. Three officers are there to meet him: Brock’s deputy, Major-General Roger Sheaffe, Lieutenant-Colonel Christopher Myers, commanding the garrison, and the brigade major, Thomas Evans. Sheaffe agrees readily to the American’s proposal that no further troops should move from the district to reinforce Brock at Amherstburg; the Americans do not know that most of the needed troops have already been dispatched. But when Van Rensselaer proposes the use of all navigable waters as a common highway, Sheaffe raps out a curt “Inadmissible!” The Colonel insists. Again the General refuses. Whereupon Solomon Van Rensselaer engages in Yankee bluff.

“There can be no armistice,” he declares; “our negotiation is at an end. General Van Rensselaer will take the responsibility on himself to prevent your detaching troops from this district.”

The British officers leap to their feet. Sheaffe grips the hilt of his sword.

“Sir,” says he, “you take high ground!”

Solomon Van Rensselaer also rises to his feet, gripping his sword. “I do, sir, and will maintain it.” Turns to Sheaffe and speaks directly: “You do not dare detach the troops.”

Silence. The General paces the room. Finally: “Be seated and excuse me.” Withdraws with his aides. Returns after a few minutes: “Sir, from amicable considerations, I grant you the use of the waters.”

It is a prodigious miscalculation, but it is Prevost’s as much as Sheaffe’s. The British general has his orders from his cautious and over-optimistic superior. Brock, contemplating an all-out offensive across the Niagara River, is still in the dark at Detroit.

The truce, which officially begins on August 20, can be cancelled by either side on four days’ notice. It ends on September 8 after President Madison informs Dearborn that the United States has no intention of ending the war unless the British also revoke their practice of impressing American sailors. By that time Van Rensselaer’s army has been reinforced from Oswego with six regiments of regulars, five of militia, a battalion of riflemen, several batteries of heavy cannon and, in Brock’s rueful words, “a prodigious quantity of Pork and Flower.” As Lovett puts it, “we worked John Bull in the little Armistice treaty and got more than we expected.” Not only has Lewiston been reinforced, but the balance of power on Lake Ontario has also been tilted. General Van Rensselaer, taking advantage of the truce, has shot off an express to Ogdensburg on the St. Lawrence to dispatch nine vessels to Sackets Harbor, a move that will aid the American naval commander, Captain Isaac Chauncey, in his attack on the Upper Canadian capital of York the following year.

In spite of his diplomatic coup, Solomon Van Rensselaer is not a happy man. Somehow, at the height of the negotiations with the British, he has managed to hold a secret and astonishing conversation with Sheaffe’s brigade major, Evans, in which he has confided to his enemy his own disillusionment with the government at

Washington, his hope that the war will speedily end, and his belief that the majority of Americans are opposed to any conflict. Solomon feels himself the plaything of remorseless fate—surrounded by political enemies, forced into a war he cannot condone, nudged towards a battle he feels he cannot win, separated from a loving wife whose protracted silence dismays him, and, worst of all, crushed by the memory of a family tragedy that he cannot wipe from his mind.

The vision of a sunlit clover lot near the family farm at Bethlehem, New York, is never far from his thoughts: his six-year-old son, Van Vechten, romps in the field with an older brother. Suddenly a musket shot rings out; the boy drops, shot through the ear, his brain a pulp. The senseless tragedy is the work of an escaped lunatic, and there is nothing anybody can do. Even revenge is futile, and Solomon Van Rensselaer is not a vengeful man. Again and again in his dreams and nightmares, he sees himself picking up the small bleeding corpse and struggling back across the field to his white-faced wife, Harriet.

It is she who worries him. The incident occurred on May 29, not long before he was forced to leave his family to take up arms. Why has she not written? Has the tragedy deranged her? Since leaving home he has sent her at least a dozen letters but has received no answer. “Why under the Heavens is the reason you do not write me?” he asks on August 21. Silence. A fortnight later he asks a political friend in Albany to tell him the truth: “The recollection of that late overwhelming event at home, I fear has been too much for her” No doubt it has. But what he apparently does not know, and will not know until the affair at Queenston is over, is that Harriet is in the final stages of pregnancy and about to present him with a new son.

His unhappy state of mind is further agitated by his political opponents, “who even pursue me to this quarter of the Globe.” The chief of these is Henry Clay’s supporter Peter B. Porter, who, in Solomon’s opinion, has with some Republican friends been causing “confusion and distrust among the Troops on this Frontier to answer party purposes against the Commander.” The Lieutenant-Colonel blames Porter, as quartermaster general of the army, for “speculating and attending to mischief and his private affairs” when the army is

in such want of supplies. The camp is short of surgical instruments, lint, bandages, hospital stores.

In Solomon’s view, Porter is “an abominable scoundrel.” He makes so little attempt to hide that opinion that Porter eventually challenges him to a duel. Solomon chooses Lovett as his second, but when his cousin, the General, hears of the affair he threatens to court-martial both antagonists. Their job, he points out, is to fight the British, not each other. Yet this quarrel reveals only the tip of an iceberg of dissension, which in the end will force the Van Rensselaers into rash action. For after the truce ends on September 8, Porter and his hawkish friends begin to whisper that the General is a coward and a traitor who does not really want to attack the heights of Queenston.