Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (85 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

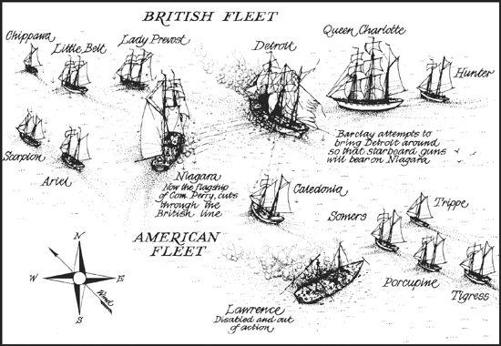

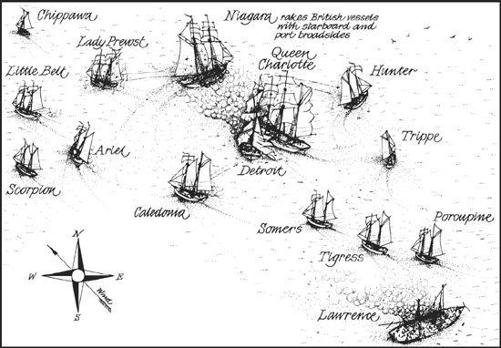

The Battle of Lake Erie: 2:40 p.m

.

As Elliott’s gunboats begin to rake the British vessels from the stern, Inglis tries to bring the badly mauled flagship around. But

Queen Charlotte

, which has been supporting Barclay in his battle with

Lawrence

, has moved in too close. She is lying directly astern and in the lee of

Detroit

, which has literally taken the wind out of her sails. Her senior officers are dead, and Robert Irvine has little experience in working a big ship under these conditions. As

Detroit

attempts to come around, the masts and bowsprits of the two ships become hopelessly entangled. They are trapped.

Queen Charlotte

cannot even fire at the enemy without hitting fellow Britons.

Only seven minutes have passed since Perry boarded

Niagara

. Now he is passing directly through the ragged British line, a half pistol-shot from the flagship.

“Take good aim, boys, don’t waste your shot!” he shouts.

His cannon are all double-shotted, increasing the carnage. As

Niagara

comes directly abeam of the entangled British ships, Perry

fires his starboard broadside, raking both vessels and also

Hunter

, which is a little astern. On the left, Perry fires his port broadside at two smaller British craft,

Chippawa

and the rudderless

Lady Prevost

. The damage is frightful; above the cannon’s roar Perry can hear the shrieks of men newly wounded. At this point, every British commander and his second is a casualty, unable to remain on deck. Looking across at the shattered

Lady Prevost

, Perry’s gaze rests on an odd spectacle. Her commander, Buchan, shot in the face by a musket ball, is the only man on deck, leaning on the companionway, his gaze fixed blankly on

Niagara

. His wounds have driven him out of his mind; his crew, unable to face the fire, have fled below.

Detroit

’s masts crumble under Perry’s repeated broadsides.

Queen Charlotte’s

mizzen is shot away. An officer appears on the taffrail of the flagship with a white handkerchief tied to a pike—Barclay has nailed his colours to the mast.

Queen Charlotte

surrenders at the same time, followed by

Hunter

and

Lady Prevost

. The two British gunboats,

Chippawa

and

Little Belt

, attempt to make a run for it but are quickly caught. To Perry’s joy, his old ship,

Lawrence

, drifting far astern, has once again raised her colours, the British having been unable to board her.

It is three o’clock. Perry’s victory is absolute and unprecedented. It is the first time in history that an entire British fleet has been defeated and captured intact by its adversary. The ships built on the banks of the wilderness lake have served their purpose. They will not fight again.

When Elliott boards

Detroit

there is so much blood on deck that he slips, drenching his clothing in gore. The ship’s sides are studded with iron—round shot, canister, grape—so much metal that no man can place a hand on its starboard side without coming into contact with it. Elliott sends a man aloft to tear down Barclay’s colours, saving the nails as a present for Henry Clay of Kentucky. Says Barclay, ruefully: “I would not have given sixpence for your squadron when I left the deck.” He is in bad shape, weak, perhaps near death, from loss of blood and the shock of his mangled shoulder, ill-used once again in the final minutes of this astonishing contest.

The Battle of Lake Erie: 3:00 p.m

.

Perry, meantime, sitting on a dismounted cannon aboard

Niagara

, takes off his round hat and, using it for a desk, scrawls out a brief message to Harrison on the back of an envelope. Its first sentence is destined to become the most famous of the war:

We have met the enemy and they are ours. Two Ships, two Brigs, one Schooner and one Sloop.

Yours, with greatest respect and esteem

O.H. P

ERRY

To William Jones, Secretary of the Navy, he pens a slightly longer missive to be borne personally to Washington by Dulaney Forrest, who still carries in his pocket the handful of grape-shot plucked from his waistcoat.

Sir—It has pleased the Almighty to give to the arms of the United States a signal victory over their enemies on this lake. The British squadron … have this moment surrendered to the force under my command after a sharp conflict.…

Around the lake the sounds of the battle have been heard, but none can be sure of the outcome. At Amherstburg, fifteen miles away, Lieutenant-Colonel Warburton, Procter’s deputy, watches the contest from a housetop and believes the British to be the victors. At Cleveland, seventy miles away, Levi Johnson, at work on the new court house, hears a sound like distant thunder, realizes the battle is under way. All the villagers assemble on Water Street to wait until the cannonade ceases. Because the last five reports come from heavy guns—American carronades—they conclude Perry has won and give three cheers. At Put-in Bay, only ten miles away, Samuel Brown watches the “grand and awful spectacle” but cannot be sure of the outcome because both fleets are half hidden by gunsmoke.

Perry returns to

Lawrence

to receive the official surrender. A handful of survivors greets him silently at the gangway. On deck lie twenty corpses, including close friends with whom he dined the night before. He looks around for his little brother, Alexander, finds him sound asleep in a hammock, exhausted by the battle. He dons his full-dress uniform and, on the after part of the deck, receives those of the enemy able to walk. They pick their way among the bodies and offer him their swords; he refuses to accept them, instead inquires after Barclay’s condition. His concern for his vanquished enemy is real and sincere.

The September shadows are lengthening. Perry’s day is over. The fever, which subsided briefly under the adrenalin of battle, still lurks. Oblivious of his surroundings, the Commodore lies down among the corpses, folds his hands over his breast, and, with his sword beside him, sleeps the sleep of the dead.

PUT-IN BAY, LAKE ERIE, SEPTEMBER 11, 1813

The American fleet, its prizes and its prisoners, are back at anchorage by mid-morning. In the wardroom of the battered

Lawrence

, Dr. Usher Parsons has been toiling since dawn, amputating limbs. The seamen and marines are so eager to rid themselves of mutilated members that Parsons has had to establish a roster, accepting his

patients for knife and saw in the order in which they were wounded. His task completed by eleven, he turns his attention to the remainder of the disabled; that occupies him until midnight. In all, he ministers to ninety-six men, saves ninety-three.

A special service is held for the officers of both fleets. Barclay, in spite of grievous wounds, insists on attending. Perry supports him, one arm around his shoulder. The effort is too much for the British commander, who is carried back to his berth on

Detroit

. Perry goes with him, sits by his side until the soft hours of the morning when Barclay finally drops off to sleep. The prisoners are struck by the American’s courtesy. Now that the heat of battle has passed, he looks on his foes without rancour, makes sure his officers treat them well, urges Washington to grant Barclay an immediate and unconditional parole so that he may recover.

To Barclay, Perry is “a valiant and generous enemy.” “Since the battle he has been like a brother to me,” he writes to his brother in England. Later, the British commander, who will never again be able to raise his right arm above the shoulder, writes to his fiancée, offering to release her from their engagement. The spirited young woman replies that if there were enough of him left to contain his soul, she would marry him. The inevitable court martial follows, at which Barclay, not surprisingly, is cleared—his mutilated figure drawing tears from the spectators. But the navy, which has used him ill on Lake Erie with help that was too little and too late, puts him on the shelf. Almost eleven years will pass before he is promoted to post rank.

In the meantime, a more acrimonious drama is in the making. Most of Perry’s officers are enraged at Elliott’s behaviour during the action; but Perry, intoxicated by victory, is in an expansive mood. There is little doubt in his mind that Elliott has acted abominably, but in his elation, as he later tells Hambleton, there is not a man in his fleet whose feelings he would hurt. It is certainly in his power to ruin Elliott’s career, but that is not his nature. Nor does he want the decisiveness of his victory marred by any blemish. “It is better to screen a coward than to let the enemy know there is one in the fleet,” he remarks, quoting a long-dead British admiral.

In his official report, he cannot ignore his second-in-command; that would be tantamount to condemnation. So he laces his account of the battle with ambiguities:

At half past two, the wind springing up, Captain Elliott was enabled to bring his vessel, the Niagara, gallantly into close action.

And:

Of Captain Elliott, already so well known to the government, it would almost be superfluous to speak. In this action he evinced his characteristic bravery and judgement; and since the close of the action, has given me most able and generous assistance.

Perry shows the report to Elliott, who first says he is satisfied but later asks for changes. He does not like the reference to his ship coming into action so late. Perry, fearing he may have gone too far, refuses to revise the document.

Elliott takes to his bed, calls for Dr. Parsons, who can find nothing wrong with him. He calls for Perry, who finds him in “abject condition” and listens sympathetically while Elliott laments that he has missed “the fairest opportunity of distinguishing [himself] that ever a man had.” Elliott follows this up with a letter in which he reports that his brother has heard rumours that

Lawrence

“was sacrificed in consequence of a want of exertion on my part individually.” He urges Perry to deny this allegation.

The good-natured Perry has already ordered his officers not to write home with their doubts about Elliott’s conduct in action and to silence all rumours about any controversy. He can do no less himself. Thus he falls into Elliott’s trap and writes a letter (which he will later describe as foolish):

… I am indignant that any report should be in circulation prejudicial to your character … I … assure you that the conduct of yourself … was such as to meet my warmest approbation. And

I consider the circumstance of your volunteering and bringing the smaller vessels to close action as contributing largely to our victory.…

This letter will be part of the ammunition that Elliott will use in his long and inexplicable battle for vindication. There is more: he is already twisting the arms of his own officers to prepare memoranda in his favour. And after Perry takes his leave of Lake Erie to go to another command, Elliott approaches Daniel Turner of

Caledonia

asking for a certificate praising his conduct in battle. Elliott tells Turner he wants only to calm his wife’s fears—she has heard the rumours—and promises on his honour to make no other use of the document. But after Turner complies, Elliott has the certificate published.

And to what end? In the hosannas being sounded across the nation, Elliott shares the laurels equally with his commander. Congress takes the unprecedented step of striking not one but two gold medals—the first time a second-in-command has received one. In this one divines the subtle hand of Elliott’s friend and mentor, Mr. Speaker Henry Clay. Elliott’s share of the prize money—a staggering $7,140—also equals Perry’s. (Chauncey, who begrudged the Erie fleet its seamen, gets one-twentieth of the total, almost thirteen thousand dollars.) As far as the public is concerned, Elliott is a hero. Why does he not keep quiet? But that would be contrary to Elliott’s temperament; he is a man with a massive chip on his shoulder and an unbridled hunger for fame. He is also a man with a guilty conscience.