Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (91 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Moraviantown’s single street is clogged with wagons, horses, and half-famished Kentuckians. The missionary’s wife, Mrs. Schnall,

works all night baking bread for the troops, some of whom pounce on the dough and eat it before it goes into the oven. Others upset all the beehives, scrambling for honey, and ravage the garden for vegetables, which they devour raw.

Richardson and the other prisoners fare better. Squatting around a campfire in the forest, they are fed pieces of meat toasted on skewers by Harrison’s aides, who tell the British that they deplore the death of the much-admired Tecumseh.

Now begins the long controversy over the circumstances of the Shawnee’s end. Who killed Tecumseh? Some give credit to Whitley, whose body was found near that of an Indian chief; others, including Governor Shelby, believe that a private from Lincoln County, David King, shot him. Another group insists that the Indian killed by Richard Johnson was the Shawnee; that will form the most colourful feature of Johnson’s subsequent campaign for the vice-presidency.

But nobody knows or will ever know how Tecumseh fell. Only two men on the American side know what he looks like—Harrison, his old adversary, and the mixed-blood Anthony Shane, the interpreter, who knew him as a boy. Neither is able to say with certainty that any of the bodies on the field resembles the Indian leader.

The morning after the battle, David Sherman, the boy who encountered Tecumseh in the swamp, finds one of his rifled flintlock pistols on the field. That same day, Chris Arnold comes upon a group of Kentuckians flaying the body of an Indian to make souvenir razor strops from the skin.

“That’s not Tecumseh,” Arnold tells them.

“I guess when we get back to Kentucky they will not know his skin from Tecumseh’s,” comes the reply.

In death, as in life, the Shawnee inspires myth. There are those who believe he was not killed at all, merely wounded, that he will return to lead his people to victory. It is a wistful hope. “Skeletons” of Tecumseh will turn up in the future. “Authentic” graves will be identified, then rejected. But the facts of his death and his burial are as elusive as those of his birth, almost half a century before.

As the Americans bury their dead and those of their enemy in two parallel trenches, Shadrach Byfield moves through the wilderness with the Indians, still fearful that he will be killed by his new companions. Toward sunset on his second night in the wild, to Byfield’s relief and delight the party stumbles upon one of his comrades, also drifting about in the woods. That night they sleep out in the driving rain, existing on a little flour and a few potatoes. The following night they find an Indian village where they are treated kindly and fed pork and corn. At last, after a further twenty-four hours of wandering, their shoes now in shreds, they run into a group of fifty escapees whom Lieutenant Richard Bullock has gathered together. With Bullock in charge, the remnants of the 41st make their way to safety.

John Richardson, meanwhile, is marched back to the Detroit River with six hundred prisoners. Fortunately for him, his grandfather, John Askin of Amherstburg, has a son-in-law, Elijah Brush, who is an American militia colonel at Detroit. Askin writes to his daughter’s husband to look after his grandson. As a result, Richardson, instead of being sent up the Maumee with the others, is taken to Put-in Bay by gunboat, where he runs into his own father, Dr. Robert Richardson, an army surgeon captured by Perry and assigned to attend the wounded Captain Barclay.

The double victories on Lake Erie and the Thames tip the scales of war. For all practical purposes the conflict on the Detroit frontier is ended. At Twenty Mile Creek on the Niagara peninsula, Major-General Vincent, expecting Harrison to follow up his victory, falls into a panic, destroys stocks of arms and supplies, trundles his invalid army back to the protection of Burlington Heights. Of eleven hundred men, eight hundred are on sick call, too ill to haul the wagons up the hills or through the rivers of mud that pass for roads.

De Rottenburg is prepared to let all of Upper Canada west of Kingston fall to the Americans, but the Americans cannot maintain their momentum. Harrison’s own supply lines are stretched taut; the Thames Valley has been scorched of fodder, grain, and meat; his six-month volunteers are clamouring to go home. Harrison is a

captive of America’s hand-to-mouth recruiting methods. He cannot pursue the remnants of Procter’s army, as military common sense dictates. Instead, he moves back down the Thames, garrisons Fort Amherstburg, and leaves Brigadier-General Duncan McArthur in charge of Detroit.

The British still hold a key outpost in the Far West—the captured island of Michilimackinac, guarding the route to the fur country. It is essential that the Americans seize it; with Perry’s superior fleet that should not be difficult. But the Canadian winter frustrates this plan. For that adventure the Americans must wait until spring. Instead, Harrison takes his regulars and moves east to Fort George, from which springboard he hopes to attack Burlington Heights.

Once again victory bonfires light up the sky; songs written for the occasion are chorused in the theatres; Harrison is toasted at every table; Congress strikes the mandatory gold medal. One day, William Henry Harrison will be president. An extraordinary number of those who fought with him will also rise to high office. One will achieve the vice-presidency, three will rise to become governors of Kentucky, three more to lieutenant-governor. Four will go to the Senate, at least a score to the House.

For Henry Procter there will be no accolades. A court martial the following year finds him guilty of negligence, of bungling the retreat, of errors in tactics and judgement. He is publicly reprimanded and suspended from rank and pay for six months.

Had Procter retreated promptly and without encumbrance, he might have joined Vincent’s Centre Division and saved his army. But it is the army he blames for all his misfortunes, not himself. In his report of the battle and his subsequent testimony before the court, he throws all responsibility for defeat on the shoulders of the men and officers serving under him. The division’s laurels, he says, are tarnished “and its conduct calls loudly for reproach and censure.” But in the end it is Procter’s reputation that is tarnished and not that of his men. To the Americans he remains a monster, to the Canadians a coward. He is neither—merely a victim of circumstances, a brave officer but weak, capable enough except in moments of stress, a man

of modest pretensions, unable to make the quantum leap that distinguishes the outstanding leader from the run-of-the-mill: the quality of being able in moments of adversity to exceed one’s own capabilities. The prisoner of events beyond his control, Procter dallied and equivocated until he was crushed. His career is ended.

He leaves the valley of the Thames in a shambles. Moraviantown is a smoking ruin, destroyed on Harrison’s orders to prevent its being used as a British base. Bridges are broken, grist mills burned, grain destroyed, sawmills shattered. Indians and soldiers of both armies have plundered homes, slaughtered cattle, stolen private property.

Tecumseh’s confederacy is no more. In Detroit, thirty-seven chiefs representing six tribes sign an armistice with Harrison, leaving their wives and children as hostages for their good intentions. The Americans have not the resources to feed them, and so women and children are seen grubbing in the streets for bones and rinds of pork thrown away by the soldiers. Putrefied meat, discarded in the river, is retrieved and devoured. Feet, heads, and entrails of cattle—the offal of the slaughterhouses—are used to fill out the meagre rations. On the Canadian side, two thousand Indian women and children swarm into Burlington Heights pleading for food.

Kentucky has been battling the Indians since the days of Daniel Boone. Now the long struggle for possession of the Northwest is over; that is the real significance of Harrison’s victory. The proud tribes have been humbled; the Hero of Tippecanoe has wiped away the stain of Hull’s defeat; and (though nobody says it) the Indian lands are ripe for the taking.

The personal struggle between Harrison and Tecumseh, which began at Vincennes, Indiana Territory, in 1810, has all the elements of classical tragedy. And, as in classical tragedy, it is the fallen hero and not the victor to whom history will give its accolade. It is Harrison’s fate to be remembered as a one-month president, forever to be confused with a longer-lived President Harrison—his grandson, Benjamin. But in death as in life, there is only one Tecumseh. His last resting place, like so much of his career, is a mystery; but his memory will be for ever green.

SIX

The Assault on Montreal

October 4–November 12, 1813

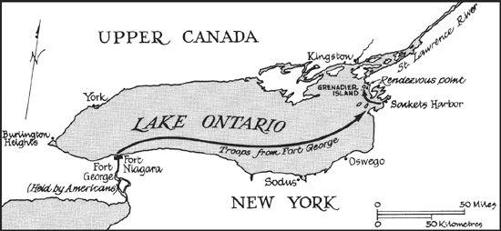

With Michigan Territory and Detroit back in American hands and the campaign on the Niagara peninsula at a standstill, the United States reverts to its original strategy—to thrust directly at the Canadian heartland, attacking either Montreal or Kingston and cutting the lifeline between the Canadas. Two armies—one at Fort George, a second at Sackets Harbor—will combine for the main attack. A third, at Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain, will act in support, either joining in the massive thrust down the St. Lawrence or creating a diversion if the attack should focus on Kingston

.

SACKETS HARBOR, NEW YORK STATE, OCTOBER 4, 1813

Major-General James Wilkinson, Dearborn’s replacement as the senior commander of the American forces, returns to his headquarters after a month at Fort George, shivering from fever, so ill that he must be helped ashore. He has been ailing for weeks; as a result, the projected attack on Montreal—or will it be Kingston?—has moved by fits and starts. The combined forces from Sackets Harbor and Fort George should have been at the rendezvous point—Grenadier Island, near the mouth of the St. Lawrence—long before this. Winter is approaching, but they have only just begun to move.

At fifty-six, Wilkinson is an odd choice for commander-in-chief. He is almost universally despised, for his entire career has been a catalogue of blunders, intrigues, investigations, plots, schemes, and deceptions. Outwardly he is blandly accommodating, with a polished, easy manner. Behind those surface pretensions lurks a host of less admirable qualities: sensuality, unreliability, greed for money, boastfulness, dishonesty. No other general officer has pursued such an erratic career. Long before, as brigadier-general, he was forced to resign because of his involvement in a cabal against George Washington. As clothier-general he resigned again because of irregularities in his accounts. As a key figure in the “Spanish Conspiracy,” a plan to split off the southwest into a Spanish sphere of influence, he resigned once more. His colleagues are unaware that he has taken an oath of allegiance to the Spanish crown and draws a pension from that government of four thousand dollars a year.

Yet he is nothing if not resilient. After the Spanish scandal he rejoined the army, rose again to brigadier-general, plotted to discredit his commander, Anthony Wayne, then narrowly escaped indictment for his association with Aaron Burr. He faced a court martial for conspiracy, treason, disobedience, neglect of duty, and misuse of

public money but, to President Madison’s dismay, the court cleared him. Now here he is, the President’s deputy, in charge of the most important military post in the United States—a living example of the poverty of military leadership in his country’s army.

Lake Ontario, October, 1813

He has been too long away from his headquarters; indeed, it is questionable whether he should have left, for the Secretary of War, John Armstrong, has quit Washington to be at the centre of the war and has all but taken over in his absence. Sick or not, the shivering general must look in on Armstrong, who shares quarters with Wilkinson’s second-in-command, the ineffectual Morgan Lewis, who is Armstrong’s brother-in-law.

Armstrong would like to have Wilkinson’s job. He fancies himself a shrewd military strategist and is not without experience, having served on the staff in the Revolution and later as a brigade commander in the militia. He likes to be called General and peppers his letters to his army commanders with military axioms and advice. Madison has no confidence in him, and James Monroe, the Secretary of State, is an avowed enemy; but Armstrong, through a politically opportune marriage, has powerful friends in New York who helped him secure his present post.