Playing the Moldovans At Tennis (14 page)

Read Playing the Moldovans At Tennis Online

Authors: Tony Hawks

BOY, DO I NEED IULIAN RIGHT NOW!

He could explain to me what on was going on, and he could tell the others that I was a nice chap and that I hadn't killed their president or done whatever it was they were upset with me about. I was innocent! I couldn't be treated in this way, did these people not know that I was a fully paid-up member of Amnesty International? My only hope was that my female admirer could save me.

What is it? What do they want?' I called across to her.

They want you go. You go. Go here. Go now,' came the reply.

'But why?'

'Because you go here for Orheiul Vecchi. We go Orhei. You go Orheiul Vecchi.'

Was this all it was? Was the driver and the entire bus up in arms because they wanted to ensure that I didn't miss my connection? It seemed unbelievable and totally out of character with my Moldovan experience to date – that anyone should care – but it seemed to be the case. I began waving my arms back at them.

'No, no!' I called out. 'I've changed my mind. I want to stay on the bus and come with you to Orhei!'

The response was extraordinary. As one, the bus fell quiet even though no-one had appeared to understand what I'd said. The passengers turned and looked to the driver for his reaction. They were going to be led by his response. He stared at me for a moment and then gestured to the door uttering an emphatic statement. A few passengers chimed in with some words of support. I was in a difficult position. These people were trying to help. They were trying their damnedest to get me to the place where I'd said I wanted to go. They were going out of their way to make sure that I didn't go out of my way. I had only seconds to make a decision. The bus had been stationary for too long now and the bus driver would surely have to continue taking his passengers to their destination soon. Did I leave the bus and therefore satisfy the driver and everyone else who was on it? Or did I hang on and leave them all frustrated and disappointed that they had been unable to prevent me from fouling up my journey? OK, not quite

Sophie's Choice,

but it's right up there.

I looked out of the window and saw more than a road junction in the middle of the Moldovan countryside. I saw a man, a foreigner, an Englishman, called Tony, stranded – unable to squeeze on to a bus, falling prey to bandits and shivering in a ditch as the night closed in. That did it, I was staying. I looked up at the driver and I shook my head to him. He shook his. I dropped my eyes to the floor. I was making it abundantly clear that I wasn't budging. I heard the driver mumble something under his breath, and observed from the corner of my eye as he threw his head back in frustration and turned to make his way back to the driver's compartment. A murmur of disapproval. Then the engine starting. The girl looked at me.

You come to Orhei?' she asked.

Yes, I come to Orhei.'

I was going to Orhei.

'Where you go now?' asked the girl, as I stood in the area of wasteland that appeared to be Orhei town centre.

'I don't know. I thought I'd get something to eat. Is there a restaurant in Orhei?'

'Restaurant? No, I do not think so.'

'No restaurant? There must be one, surely?'

'Maybe. Come with me.'

Maybe. How, I mused, had I ended up in a country where the answer to the question 'Is there a restaurant?' was 'maybe'?

As we climbed some steps to the part of town where this restaurant might be, I learned that my companion was Rodica, a 21-year-old who worked as a secretary in Chisinau and was returning to Orhei for a weekend visit to her parents. Her knowledge of English was so limited that establishing this information filled the entire ten-minute walk to the ugly concrete block outside which she was now leaving me.

Thank you,' I said. You are very kind.'

'And you are very nice.'

Thank you again.' I pointed to the run-down building to our left. 'Is the restaurant in here?'

'I think so.'

Looking at the building I could see why there was an element of doubt. It was falling to pieces and looked deserted. If, in having met the nice Englishman, Rodica had something of a story to tell, then she certainly wasn't going to dine out on it. Not in this town, anyway.

Well, goodbye then,' said Rodica, rather plaintively.

'Yes, goodbye,' I said, shaking her hand.

Lovely Rodica. She'd been so kind, and but for an accident of dentists we could have been made for each other.

'Do you have a telephone number in Chisinau?' I asked, drawn to the idea that I should repay her hospitality by taking her out for a nice meal there next week.

'Yes I do,' she replied, beaming broadly, and as a result not really presenting herself at her best.

With some enthusiasm she wrote her number neatly on a piece of paper and handed it to me.

Thank you,' I said, 'I shall call you.'

'I hope so. Enjoy you meal.'

'OK Goodbye.'

Rodica smiled again and then turned from me, rather self-consciously. I watched her walk away, back to the world of her mother and father, back to the world of her youth. Did I detect a slight spring in her step? Had she construed the taking of her number to be a friendly gesture which had broken the monotony of a routine day, or as a sign that I might be some kind of Western knight in shining armour, ready to whisk her off to a land where the restaurants outnumbered the problems? At the street corner she looked back and saw that I was still watching her.

'I hope you can clean good your trousers,' she called out with an accompanying wave, before disappearing between the buildings which formed the jaws of the adjoining street.

I looked down and saw that the entire crotch area on my trousers had been blackened by the rubber from the bus spare tyre. It looked ugly and it looked unsavoury. It looked like I used my leisure time with an unwholesome creativity. Maybe that was why Rodica had not chosen this occasion to introduce me to her parents:

This is Tony from England. He likes to fuck tyres.'

That's me. Always ready to be an ambassador for my country.

'So how did you like Orheiul Vecchi?' asked Adrian, as we sat down in the kitchen, the kettle toiling towards boiling point.

To my relief I'd been able to sneak upstairs and change my trousers before bumping into any family members.

'I didn't go to Orheiul Vecchi. I went to Orhei,' I replied.

'But Orhei is boring.'

'Yes, that's why I got the bus straight back.'

'It is a shame that you did not go to Orheiul Vecchi.'

'Yes.'

'Orheiul Vecchi is interesting.'

All right, don't rub it in.

Actually, Adrian was displaying a mischievous side here. He'd realised that I'd completely failed to reach my intended destination, in spite of only that very morning boasting that I didn't know the meaning of the word 'failure'. In his own gentle and unassuming way he was making a point. In the unofficial and undefined tussle which was taking place between the two of us over the credibility of my positive philosophy, Adrian had scored valuable points. His lead, which was already substantial, was to be extended later that night.

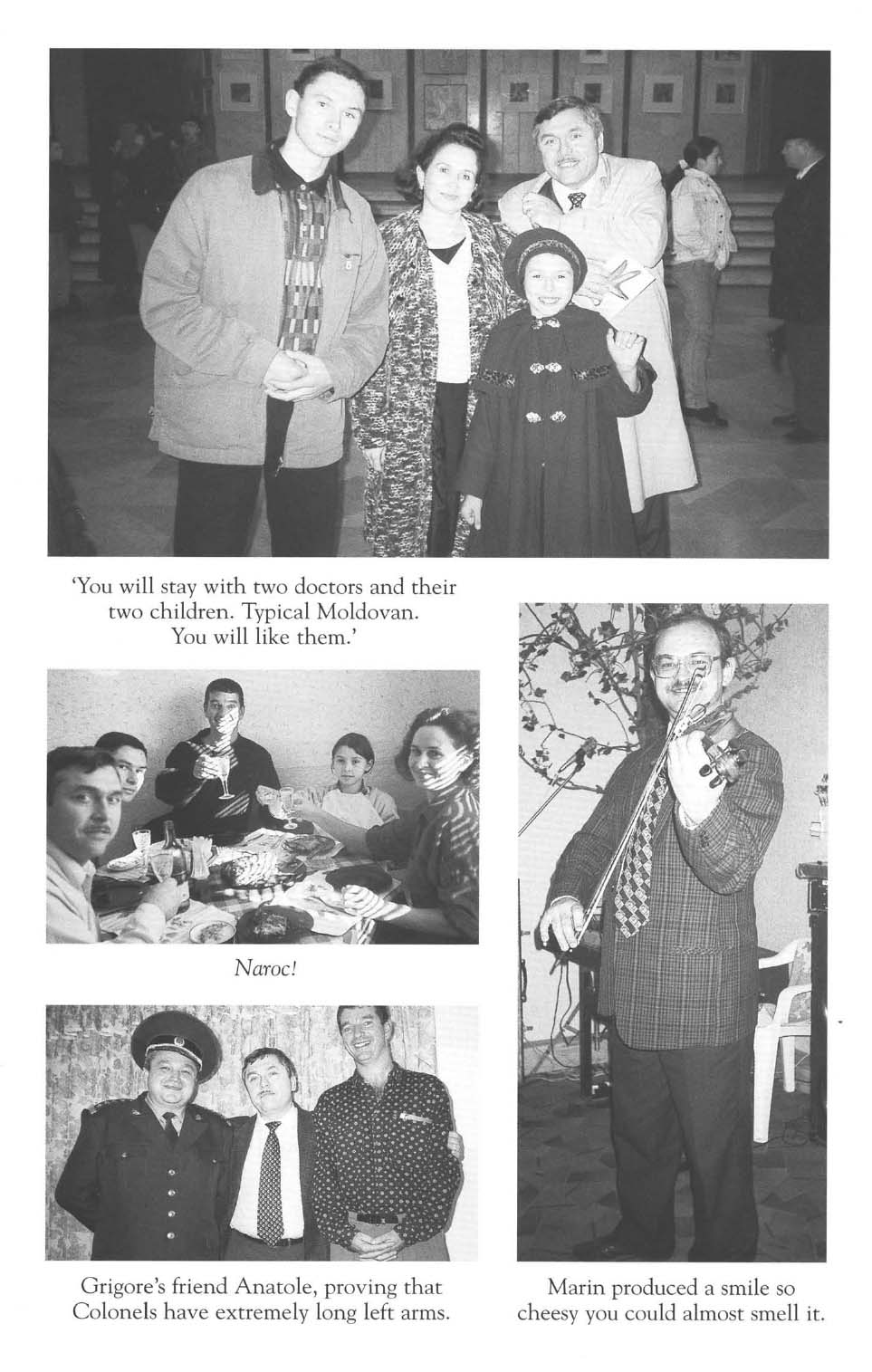

The occasion was a recital of Rachmaninov at the Filarmonica, Chisinau's Concert Hall. One of Dina's patients, a violinist in the city's prestigious orchestra, had given her a couple of tickets for tonight's recitation and I was invited to accompany Adrian to the concert, if I so desired. Looking through my diary and finding myself unexpectedly free of social engagements that night, I happily accepted.

The Filarmonica was yet another example of austere Soviet architecture. It was physically cold (the absence of any heating meant that the audience would remain in their coats throughout the evening's proceedings) and as Adrian and I filed in to take our wooden seats, it felt like we were attending school assembly rather than a musical recital. The only concessions to the aesthetic were a huge chandelier hanging from the ceiling and some second-rate portraits of famous composers on one of the walls. We sat down. Hard seats. The dim lights began to dim still further. The concert was about to begin.

I'm no connoisseur of classical music but I've been known to be surprisingly moved by its live performance. Rachmaninov's Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 2 in C minor provided another such occasion. As well as the passion of the music, there was the visual spectacle to be enjoyed – the unison bowing of the string section, the extravagant flamboyance of the solo pianist, and the enthusiastic arms and flashing white baton of the conductor. It was by turns, spellbinding, soothing, inspiring and uplifting. Certainly there were flaws in the performance, notably the musicians not having learnt the piece and having to bring the sheet music on with them, and Rachmaninov's second movement having been unashamedly plagiarised from the Eric Carmen hit 'All by myself (Rachmaninov was well known for this – he did the same with the theme to the South Bank Show), but I was prepared to overlook these details. The whole thing was rounded off perfectly when the cymbal player, who had stood with an admirable stillness throughout, finally got to do a bit of crashing in the climactic crescendo which preceded the interval. I'm sure he was thinking, as he walked off stage with three crashes in forty minutes under his belt, 'I was magic tonight.'