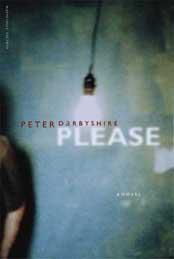

Please

Please

by Peter Darbyshire

2002

I COULDN'T LIVE LIKE THAT

I WALKED EVERYWHERE in those days. I had a car but I couldn't always afford gas. Sometimes, at night, I went up to the windows of houses and looked inside. In the dark, you can stand right on the other side of the glass, and no one ever knows you're there. From the street, these places always seem like the kind of homes you see in magazine ads, all red walls and leather furniture. Close up, though, it's mostly just people watching television or doing the dishes. Although once I saw a woman feeding soup to a man with two broken legs. There was nothing wrong with his arms but she fed him soup anyway, kneeling beside him on the couch and carefully lifting the spoon to his lips.

Another time I saw a man putting on eyeliner. I was standing deep in a driveway between houses and looking into a bedroom. I could see him through the cracks between the blinds. He was sitting at a vanity with lights around the mirror. When he was done with the eyeliner he put on eye shadow and lipstick. Then he cleaned his face with a tissue and blew himself a kiss. After that, he walked out of the room and didn't come back. I wondered whose makeup it was. His wife's? His roommate's?

And once I came across another man doing the same thing as me. I started down a driveway and saw him kneeling on the ground at the other end, his face shining from the light of the basement window in front of him. He never looked away from it, not even when I went back up the driveway. I don't think he ever knew I was there. I never went back to that house again.

I was twenty-three or twenty-four at the time, I can't really remember anymore. I hadn't worked in months. My wife had left me. Sometimes I woke up with shooting pains in my stomach, like someone had stabbed me while I slept. The doctors said there was nothing wrong with me.

ON ONE OF THESE walks I met a blind man. It was around five or six in the evening. I could tell he was blind by the fact that he wore those dark glasses and he was tapping around the base of a telephone pole with a long, white cane. When I tried to walk around him, he swung the cane into my legs. It bent like it was made of rubber. I had to stop because he kept the cane in front of me. I couldn't move without jumping over it.

"I'm a little lost," he said, as if I'd asked him how he was. "There's not a newspaper box around here, is there?"

"No, there's nothing but the telephone pole," I told him.

"There's supposed to be a newspaper box," he said, "but I guess my counting got thrown off somewhere."

"Yes, that's most likely it," I agreed, even though I didn't really know what he was talking about. I waited for him to move the cane but he didn't.

"I was walking to the school," he went on. "But I should have come across it by now. You don't see a school anywhere, do you?"

I looked around. We were standing in front of an old Victorian house with vines growing up the front of it. A young girl in white pajamas stood in the front window, watching us. There weren't any lights on behind her. She was just a white silhouette against the darkness. I wondered where her parents were.

"No," I said, "there's nothing but houses around here."

"Wow," he said, shaking his head. "I'm really messed up."

The girl didn't move at all, didn't even seem to blink. She looked like a ghost, and for some reason, that thought reminded me of the last night I ever saw my wife.

"I could really use some help here," the blind man said.

THE BLIND MAN KEPT his free hand on my arm while we walked, as if he was afraid I would run away if he didn't. All the way down the street, he tapped the ground in front of us with his cane and counted under his breath. Now that I was taking him back the way he had come, he seemed to know exactly where we were at all times. Every intersection we took, he guided me in a different direction. Soon I was the one who was lost.

"I have it all memorized," he told me as we went along. "I go for the same walk, to the school and back, every night. Turn left out the door, two hundred and twenty steps to the first right, four hundred and ten from there..." He went on like that for some time and then ended with, "And that box has always been there before, a hundred steps from the intersection, give or take, after the second left turn. Always. I don't understand it."

"How do you know when you're actually at the school?" I wanted to know. "I mean, even if you take the proper amount of steps, how do you know it's the school and not something else, like a bank or a high-rise?" I pictured him tapping his way around a building, trying to figure out what it was just by its size and shape. Maybe counting taps like he did steps.

"I can hear the kids," he told me. "There are always kids in the playground, even in the middle of the night. It's like they don't know where else to go."

Later, he said, "You're probably wondering why I go to the school every day."

"No, not really."

"I'm not after any Lolitas, if you know what I mean."

"No, I don't."

HE LED ME TO a large house with a fence around the front yard. The fence was taller than me and had trees all around the inside of it. The address was printed on the door, in red paint. It looked like a child had done it.

"Here we are," he said.

"Why do you have such a big fence?" I asked. None of the other houses on the street had fences around their front yards.

"It's so no one can see us," he said. "I think the neighbours complained or something."

"Us?" I asked.

"It's kind of like a group home," he said. "For people like me."

I pictured a whole houseful of blind men, bumping around the halls and asking each other for help just to get out the door.

"Would you like to come in?" he asked. "For a coffee or something?"

"I don't think so," I said.

"Maybe something to eat," he said. "I can make you a sandwich."

"No, I've really got places to be," I told him.

"I have drugs."

HE LED ME THROUGH the front door, which wasn't locked. As soon as he opened the door I heard a woman scream, then the sounds of gunshots. I was ready to run away, or maybe hide behind one of the trees, but he walked in like this was normal, so I followed him.

Just inside the entranceway was a large living room, and this was where all the noise was coming from. Two men were sitting on a couch underneath the window, watching a big-screen Sony across the room. On the television, some cops in black body armor were standing around a man lying on the ground. He was wearing nothing but shorts, and blood was running out of several bullet holes in his upper body. A woman was standing on the porch of a house in the background, and she was the one who was screaming. I wasn't entirely sure, but I thought I might have seen this before.

The two men on the couch turned to look at us when we came in, but they didn't say anything. One of them raised a beer can to his lips. "Hello," I said. They still didn't say anything.

"Don't mind them," the blind man said. "They're deaf."

They looked back at the television when the scene changed to an outdoors shot. Now a bear was mauling someone on the other side of a parked car. Someone had videotaped the whole thing rather than help. The deaf men started laughing, making noises like barking dogs.

"It's just down this way," the blind man said, leading me deeper into the house.

FOR A WHILE during these days I dated a woman who had a metal arm. It was the first woman I'd been with since my wife. She'd lost her real arm in a car accident. She talked about the accident like it didn't mean anything to her. "We were going too fast around a corner and the car rolled. That was it, just one of those stupid, one-car accidents." She never said who the other person was, or which one of them was driving. "Silly me, I had my arm hanging out the window and it got torn off when the car rolled over it." Silly me. She really said that.

She didn't mind having a metal arm at all. Not that it looked metal. When you put it beside her real arm, you could barely tell them apart. But when you touched this fake arm, it was cold and hard. And it would move on its own. She would take it off and lay it on her dresser, but the fingers would twitch for hours afterwards, and sometimes the elbow would even bend. "It's just going to sleep," she told me. But one night she was moving around and whimpering with some dream, and the arm matched all her movements. It jerked and shook on the dresser, and the fingers balled up into a fist, and then the whole thing fell on the floor. I wouldn't get out of bed the next morning until she'd picked it up and put it back on.

She lived in a basement apartment with only one window. We had to leave the bedroom door open while we slept for fear we'd suffocate. She couldn't afford anything else because all she had was some sort of disability pension. She wanted to be an actress but she hadn't worked as anything but an extra in years. Who would hire a woman with only one arm?

We liked to tour condos that were for sale. Only the new ones, though, never anything that had already been lived in. We'd walk through them and make notes in a little notebook we'd bought, talk about the view, look in the cupboards. The salespeople acted like they believed we could actually afford these places.

One woman opened a bottle of wine for us while we were there. She gave it to us in little plastic glasses. "I'm sorry about that," she said, "but would you believe someone actually stole our real wineglasses?" It was the best wine I'd ever had.

When the woman asked us what we did, I told her I was a marketer for IBM, and my girlfriend said she was a nurse.

This woman showed us around the model suite. When she brought us to the living room, the sun was just setting, as if she'd cued it. The entire place filled with a golden light, and I held my girlfriend's hand -- the real one -- until it passed.

"Now there's a Kodak moment if I've ever seen one," the saleswoman said.

My girlfriend stood in the middle of the smaller bedroom and looked around. It was a young boy's room, with blue walls and a bed in the shape of a racecar. "We'd want to paint, of course," she said. "When we have the children."

"Are you expecting?" the saleswoman asked.

"Oh no," my girlfriend said. "But someday." She looked at me and laughed.

"Cheers then," the saleswoman said and refilled our glasses.

She took us into the kitchen last and sat us down around a glass-topped table. There was an espresso maker on the counter and the fridge had an icemaker.

"Does the place come with all the appliances?" I asked.

"Oh yes," the woman said. "And there's a pool and a sauna in the building."

"A pool and a sauna," I repeated.

"That's right."

"And we don't have to pay for that?" my girlfriend asked. "We can just use it like everyone else?"

The woman gave us a blank contract to look at, and a pamphlet full of measurements and costs. I looked at all the numbers and said, "I don't know. I think it's a bit more than we wanted to pay."

"It always is," she said, still smiling.

"I mean, I don't know if we can afford a place like this," I said.

"But if we could," my girlfriend said and shook her head.

The saleswoman poured the last of the wine into our glasses. "The question you need to ask yourself," she said, "is how can you afford not to have a place like this?"

MY GIRLFRIEND EVENTUALLY left me for a man with an artificial leg, someone she'd met in her amputee support group. They'd been having an affair for months, pretty much the whole time I'd been dating her. She told me over breakfast one afternoon.

"What are we going to do now?" I asked, unbelieving.

"I don't know what you're going to do," she said, watching the fingers of her fake hand flex on the table, "but I know what I'm going to do."

"His cancer is going to come back, you know," I told her. "It's just growing somewhere else in his body right now."

"Well, if my mind wasn't made up about you before," she said.

"One day he's going to start having seizures because of a brain tumour or something. Where will you be then?"

Her hand spread itself out flat on the table and was still. She looked at me. "I won't be sitting here having this conversation with you," she said.