Poison (26 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

Seven hours after taking off from Toronto, Korol and Dhinsa’s flight touched down at London’s Heathrow Airport, at 9:45 a.m. local time on April 29. A two-hour layover, then they boarded the plane for the eight-hour flight to New Delhi. It was 1 a.m. local time on April 30 when they touched down. The trip to India is exhausting. The body’s internal clock has to adjust to the 10-hour time difference from Eastern Standard Time. The detectives disembarked at Indira Gandhi International Airport and headed to the baggage claim under colored sashes and streamers, decorative dolls hanging from a ceiling that was as low as a parking garage’s. They spotted a driver from the Canadian High Commission holding a sign with their names on it.

Exiting the car at the hotel, the heat, even at 1:30 a.m., hit them like hot water exploding from a burst pipe. Pierre Carrier had put them up at the Hyatt, a six-star palatial oasis with walls made of Indian sandstone, a sprawling pool in back. It was the finest hotel the detectives had ever stayed in. They shared a room and were asleep by 2:30 a.m. Five hours later they were up, showered and dressed, and headed down to meet Carrier in the hotel lobby. Carrier’s driver took them through New Delhi to the Canadian embassy—still called a High Commission, in keeping with the tradition for British Commonwealth countries (even though India does not recognize the Queen as its head of state). Korol learned that anyone who can afford to do so hires a professional driver in India to navigate the chaos on the roads. Hindu drivers place little god figurines on their dashboards to look over them on the roads. “Three things you need driving in India,” the driver said. “One, good brakes. Two, good horn. Three, good luck.”

CHAPTER 14

TO LIVE AND DIE

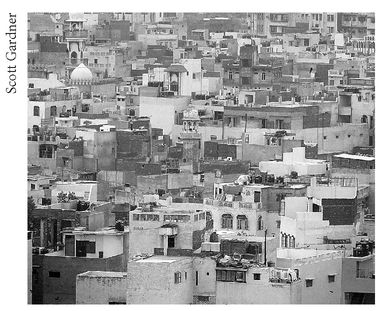

Warren Korol had done the Caribbean vacation thing, but had never ventured further afield, so he was instantly overwhelmed by New Delhi. With its 12 million people, the city is home to India’s central government. It was planned and built by the British in 1932 when they decided to move the capital from Calcutta. The city embodies India’s contradictions. There’s the stench of poverty in Old Delhi, the seventeenth-century Muslim walled city within the capital where merchants still slit the throats of lambs in open-air markets, the blood trickling across the pavement. In the modern part of the city are the attractive white bungalows (“bungalow” is an Indian word) that once housed British generals and are now occupied by Indian government officials whose children, dressed in their powder-blue uniforms, walk home from government schools.

The aerial view from a tower in Old Delhi

New Delhi tries to do what no other Indian city can: regulate order in the midst of chaos. Signs at intersections warn that horn honking is outlawed to cut back on noise pollution, even as traffic chokes the roads every hour of the day. Air-pollution laws ban diesel fuel for auto rickshaws, which line up for five hours at a time for government-approved clean gas pumps. There is a seat-belt law, but most of the cars are designed without belts in the back. There is a helmet law for motorcyclists, but only for the driver, not the women in flowing dresses who ride on the back side-saddle (a more modest position than straddling) or the bare-headed sleeping babies perched precariously on their laps. The well-kept paved streets are often shaded by a canopy of trees; men stand in rows and casually urinate in public against elegantly designed bridge walls.

Korol, Dhinsa, and Carrier were chauffeured up the long boulevard called Shanti Path, or “peace way,” home to several embassies. The German mission was across the street from Canada’s. The American embassy was a walled fortress with a massive stars and stripes in front, and a huge fountain (“There’s Big Brother,” the driver quipped). They passed the embassy of India’s neighbor and rival, Pakistan (“There is India’s true friend,

Pakeestahn

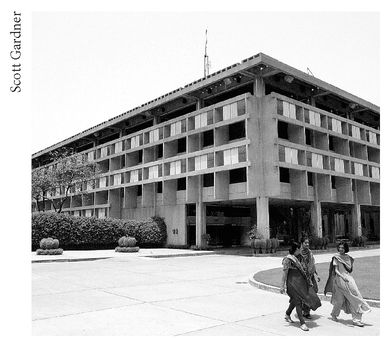

,” the driver said, sarcastically). Barbed wire lined the top of the wall that surrounded the Canadian High Commission, where a sentry holding a rifle stood on guard. Not far from the embassy gate, a group of Sikhs sat in the shade of trees lining the boulevard, waiting to apply for visas for Canada. Inside the building, Carrier introduced the detectives to the High Commission’s staff physician, Dr. Govind Prasad.

Pakeestahn

,” the driver said, sarcastically). Barbed wire lined the top of the wall that surrounded the Canadian High Commission, where a sentry holding a rifle stood on guard. Not far from the embassy gate, a group of Sikhs sat in the shade of trees lining the boulevard, waiting to apply for visas for Canada. Inside the building, Carrier introduced the detectives to the High Commission’s staff physician, Dr. Govind Prasad.

The Canadian High Commission in New Delhi

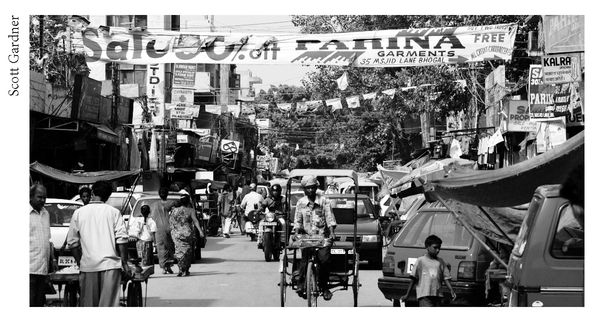

“Where can we buy strychnine?” Korol asked, anxious to get started, adrenalin masking his jetlag. Prasad suggested Bhogal market. New Delhi has hundreds of markets, but tour guides suggest avoiding taking first-time visitors to Bhogal, one of the largest and most congested.

The driver parked at the market and the three Canadians stepped from the air-conditioned car. It was now high noon and the heat hit like a brick. Korol had heard about Indian heat. It was another thing to feel it. Even the breeze against his damp forehead was hot. The heat beats up newcomers, the body instantly bathed in sweat as the heart pumps harder to adjust. The head feels compressed, feet roast inside shoes, a pouch strapped around the waist burns like a hot coal. Most Indians carry cloths to wipe their faces, although few seem to wear hats or sunglasses. No Indian man wears shorts;

better to wear pants to shield the skin. There is a walk, notable among Indian men, a loping stride, feet barely leaving the ground, arms heavy and swinging with their own momentum, the body shutting down every unnecessary muscle, storing energy.

better to wear pants to shield the skin. There is a walk, notable among Indian men, a loping stride, feet barely leaving the ground, arms heavy and swinging with their own momentum, the body shutting down every unnecessary muscle, storing energy.

The heat and bustle of the markets overwhelmed the detectives.

The bustle of the market assaults the senses. Cars, bikes, and rickshaws squeeze among the many stores and kiosks and merchants—the cobbler, tailor, outdoor barber, dye man twirling cloth in a vat of hot blue liquid, auto repair, appliance repair, fruit and vegetable stands, the thin man with ribs and vertebrae pressing through his leathery dark skin as he squats barefoot beside a large pot of oil, cooking samosas. Young boys stroll the streets in pairs, holding hands or arm in arm. It is a common yet paradoxical sight in India, with its macho male culture, this unabashed affection that young men show each other. Men rarely show any public affection toward women, no hand-holding and absolutely no kissing.

Their size alone made Korol and Dhinsa stand out in the crowd. Children called out, “Hey Jim!” as Korol walked down the street. Men stared; women were more subtle in casting glances. Dhinsa approached a shopkeeper who sold pesticides and asked in Punjabi for

kuchila

. Dhinsa bought a brown envelope labeled “rat poison” for five rupees, mere pennies in Canadian money. It was not quite what they were looking for. They wanted to buy raw

kuchila

.

kuchila

. Dhinsa bought a brown envelope labeled “rat poison” for five rupees, mere pennies in Canadian money. It was not quite what they were looking for. They wanted to buy raw

kuchila

.

Later, they headed to the CBI. On the main floor, the trio met Superintendent H.C. Singh, in charge of Interpol affairs. Singh’s assistant presented a tray of tea and ice water. It would be the same everywhere the detectives went, drinks always offered in the Indian tradition. Singh gave Korol a copy of sections 161 and 162 of the Indian Criminal Code, stipulating that if Indian police take a witness statement, the witness must not sign it, a legacy of India’s tradition of coerced statements.

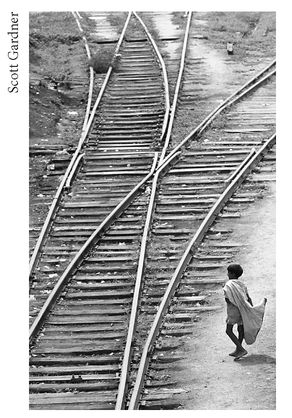

The next day Korol and Dhinsa rode from their hotel to the New Delhi train station. Taking the train north to Chandigarh was Dhinsa’s idea. They could have been chauffeured in a car, a four-hour drive, or could have flown. But the train was a throwback to Dhinsa’s childhood, the days when he reveled in riding the rails to his grandfather’s farm in Haryana province, watching the scenery whip past. It would be a good chance for Warren to see the countryside up close. And they could afford to ride first class. But the trip turned out to be a rude homecoming for Dhinsa. They boarded the Shatabdi Express. It was early morning, the platform at Delhi’s train station slowly stirring to life. People slept on the concrete floor. A little boy walked up and down the platform with his shoe polishing kit, calling, “Shine? Shine?” There was litter on the platform, human excrement between the tracks. Dhinsa was appalled. It wasn’t how he remembered it.

The Shatabdi’s “deluxe air-conditioned seat car” is the pride of the railway. But this, too, was hardly the experience Dhinsa remembered. It was indeed air conditioned and it had seats—in Indian terms that made it deluxe. Most Indians ride rail cars with wooden benches and hang out the windows to beat the heat inside. A one-way ticket in the cheap seats costs 100 rupees, about three Canadian dollars. As the train inched away from the platform, stray cows and wild dogs crossed the tracks ahead. The train picked up speed, providing a collage of images. There were the shanties, looking as though they had been thrown up by the earth, barely standing, smashed brick and wooden shacks with crumpled tin roofs. Land along train tracks is considered public in India, and officials allow squatters to live there. The heat of the morning rose, the sun burning off the haze like a hot ember through tissue paper.

And then the view suddenly shifted, a contrast to the bleakness, the picture out the window shifting to color, the fields green with cane and corn and elephant grass, a pump house pouring water onto a rice paddy. Women far off in the fields hunched over in their purple and orange dresses, backs bent to the sun now high in the sky. The flooded rice paddies glowed like green neon under the hazy pewter sky.

And then the view suddenly shifted, a contrast to the bleakness, the picture out the window shifting to color, the fields green with cane and corn and elephant grass, a pump house pouring water onto a rice paddy. Women far off in the fields hunched over in their purple and orange dresses, backs bent to the sun now high in the sky. The flooded rice paddies glowed like green neon under the hazy pewter sky.

The detectives rode the train to Chandigarh.

More settlements passed, the train shaking and clacking through them, signs declaring places such as Narela, Bhani Khurd, Kurukshetra, Ambala. Women and children huddled in an abandoned rail car and in the shade of an underpass.

The train glided past the station platform of a town called Panipat. The developed part of Panipat is situated along the road from Delhi to Chandigarh and is a typical beehive of markets and commerce. Panipat is best known for its pickles. But along the tracks was the other Panipat, the underbelly. Cloistered inside the train, Korol and Dhinsa looked out on the most brutal existence they had ever seen, a life of black and gray interrupted by an occasional flicker of orange from piles of burning garbage. In this wasteland, women picked through trash, cows and naked children waded in stagnant water as black as tar, trying to escape the heat. A thin old man sat in dirt with his head clasped in his hands.

Other books

Blue by You by Rachel Gibson

The Zenith by Duong Thu Huong

The Dragon Turn by Shane Peacock

Alien Mate (Zerconian Warriors Book 3) by Sadie Carter

Origin by J.T. Brannan

Summertime Death by Mons Kallentoft

Naughty Nights: A Bad Boy Romance by Sophie Brooks

A LITTLE BIT OF SUGAR by Brookes, Lindsey

Beneath a Spring Moon by Becca Jameson, Lynn Tyler, Nulli Para Ora, Elle Rush

Outside Hell by Milo Spires