Poison (5 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

I make oath and say as follows: On 11 Sept. 1996, I was assigned a suspicious death investigation.

That’s when everything changed, when the days of football and the paddy wagon rapidly receded in life’s rear-view mirror. The new assignment would consume Warren Korol, take him across the world, his ambition and the Byzantine case of the serial killer pushing him deeper and deeper into a stew of violence and lies, testing his will, his professional and his personal life, drawing hate out of him like never before.

Hamilton, Ont.

February 1995

February 1995

Sukhwinder Dhillon drew stares as usual when he emerged from the gym locker room. He wore a garish yellow track suit, matching top and pants. It was 7:30 a.m. at Family Fitness Center on Barton Street in east Hamilton. He liked working out in the morning when his friends were there. He did not stretch, wandered to the bench press, loaded two 25-pound plates, lay on his back, wrapped each hand around the bar, and lifted. One. Two. Three. Four. Five. The bar clinked back into place. He stood and moved on. A spotty workout, as usual. But so what? He was already a big man, a strong man. Everyone knew it. He did a few situps, couple of pushups. Then the treadmill, barely breaking a sweat. Back to the locker room.

Dhillon was average height, perhaps five-foot-ten, and over 200 pounds, his shoulders broad, arms thick, but the stomach was soft and round. The dark eyes stared back at him in the mirror. Alarmingly, the ink-black color in his beard was marred by specks of gray. Dhillon was almost 36 years old, and he couldn’t stand it. He showered, returned to his locker, retrieved the toothbrush and bottle. Back at the mirror, inches from his reflection, he dipped the brush in black liquid and colored the bristles. Across the room, two Indian men smiled. They had seen him paint his beard, and even his hair, before in the locker room. It got them every time. Dhillon. That guy. The vanity. He was like a woman. They shook their heads.

“You know, Dhillon, if you’re going to do that you should do it at home,” one of them said. He shrugged, said nothing and continued. He always heard the chuckles. He didn’t care. After he dressed, it was off to work. He sold used cars. Loved to wheel and deal. And there were other deals in the works, too. Deals? Was that the word for it? Well, he had recently received the $2,850 insurance payout on the fender-bender. And five months before, for $2,325. Same car. A nice deal, auto insurance. You pay a little money and make a lot more. Accidents happen. Sometimes you can make them happen.

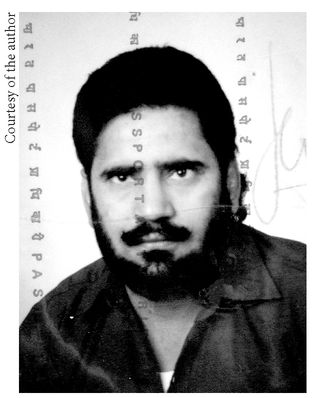

Sukhwinder Dhillon’s passport photo

Sunday, March 7, 1995

Ludhiana, India

Ludhiana, India

Four weeks after Parvesh died, Dhillon landed in New Delhi, India, after the 14-hour flight from Toronto. He had a long trip planned, two months. Business and pleasure. His destination was his hometown, Ludhiana, an eight-hour drive north of the Indian capital. He bounced along the ragged Indian roads in his compact, white, Indian-made Maruti, one of the relatively privileged Indians to own a car, a bottle of Aristocrat whisky under the seat. The Maruti was like a toy, too small for Dhillon’s thick frame. Imagine if he had his Lincoln here! In India he proudly showed friends the home movie of himself in his driveway in Hamilton, leaning against the massive car, wearing cowboy boots and duster trench coat, holding a cellphone.

On the road out of New Delhi, traffic cops in tan uniforms occasionally pulled a motorist over, in some cases offering the driver a chance to pay his way out of a ticket

.

“Give me 50 rupees and I’ll forget about the ticket for 100 I’m about to give you.” Trucks and scooters, rickshaws and horse-drawn carts and goat herders jockey for position on the two-lane highway. Coca-Cola signs dot roads running through villages where sidewalk commerce spills nearly into the path of the traffic. “

Life ho to aisi

,” one sign declares, meaning, literally, in English, “If life is there, it has to be this.” Dhillon zipped past fields of sugar cane and rice, women walking along the road carrying crops on their heads and wearing purple and green dresses that flowed in the warm wind.

.

“Give me 50 rupees and I’ll forget about the ticket for 100 I’m about to give you.” Trucks and scooters, rickshaws and horse-drawn carts and goat herders jockey for position on the two-lane highway. Coca-Cola signs dot roads running through villages where sidewalk commerce spills nearly into the path of the traffic. “

Life ho to aisi

,” one sign declares, meaning, literally, in English, “If life is there, it has to be this.” Dhillon zipped past fields of sugar cane and rice, women walking along the road carrying crops on their heads and wearing purple and green dresses that flowed in the warm wind.

Who was the young woman Dhillon would soon meet? What would she look like? He would be having sex before long. Who should he take as his bride?

Hamilton General Hospital

Forensic Pathology Department

Forensic Pathology Department

Through February and into March, Dr. David King continued working on the postmortem report. He studied samples of hardened, sliced brain tissue under a microscope. There were no scars. But there had been swelling of the brain, a sign of oxygen debt. Lack of oxygen, but why? Parvesh Dhillon: a young woman, relatively healthy. She does have a history of headaches. A tumor could possibly have gone undetected. But it would be unlikely that an undetected, microscopic tumor could have caused a seizure powerful enough to kill her. An epileptic seizure could be the cause of death. It certainly had earmarks of it. Except Parvesh wasn’t epileptic. Murder? A forensic pathologist, King liked to say, has an unusually low threshold of suspicion. Medical students sitting before him were told the basic rule of forensic pathology—suspect the worst. “Not that we’re paranoid,” he said in his British accent, “but it’s our job.”

It was part of King’s wiring to consider foul play and criminal poisoning from the start. The professional memory unwound in his mind, 30 years on the job, his vast library of cases, back to his education at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, England. Poisoning cases? There was the cyanide case he worked 15 years earlier. Police were stumped over a man’s sudden death. King examined the body, noticed something on the tissue, and asked a cop, had the deceased ever been involved in photography? Well, yes, he had. King knew that cyanide was once used as a chemical component in developing processes. The man had access to it. Suicide. Case closed. No cyanide in the case of Parvesh Dhillon, though.

Tetanus? It causes prolonged, painful death, stiffness in its victims. But there would be a puncture wound of some kind. Her skin was unmarked. Other poisoning cases? Actually, that was precisely the title of one chapter in the classic 1950 biography of the Englishman Bernard Spilsbury, a pioneer in forensic pathology. At 18 years old, King gave his father, a family doctor, the Spilsbury biography for his birthday. The

son also hungrily devoured the forensic bible himself. Spilsbury specialized in discovering poison in corpses, often long after burial. Spilsbury, the gentleman pathologist, King’s hero. The legend once showed up at a graveside, dressed immaculately in a dark top hat. The coffin raised, Spilsbury ran his nose along it, straightened himself, cleared his throat and said, simply, “Arsenic, gentlemen.” Arsenic? No, gentlemen, not in the Parvesh Dhillon case. So what, exactly, was the damned answer? King had none.

son also hungrily devoured the forensic bible himself. Spilsbury specialized in discovering poison in corpses, often long after burial. Spilsbury, the gentleman pathologist, King’s hero. The legend once showed up at a graveside, dressed immaculately in a dark top hat. The coffin raised, Spilsbury ran his nose along it, straightened himself, cleared his throat and said, simply, “Arsenic, gentlemen.” Arsenic? No, gentlemen, not in the Parvesh Dhillon case. So what, exactly, was the damned answer? King had none.

Parvesh suffered from anoxic brain damage, or a lack of oxygen to the brain. He didn’t know why. Years later, King would lament this case. In forensic pathology you spend a lifetime learning from your mistakes and those of others. He would never make the same mistake again. Except King was nearly retired. The harsh lesson would help another forensic pathologist, someday. What bothered him most was that, in hindsight, the clues were there. Not obvious, not at all. Making the connection would have been difficult for any forensic pathologist, regardless of experience.

For one thing, he didn’t notice the contradiction between the claim in the hospital staff notes that the husband had given Parvesh a Fiorinal capsule, a barbiturate, and the drug screen just a few hours later showed no presence of the substance. At the time, the discrepancy didn’t ring a bell with King. But it should have. There was something else. He missed the key word in a note describing Parvesh’s “opisthotonic” position. The word was both misspelled and scrawled messily, and King’s eye had skipped right over it during his initial review of the charts. Had he deciphered the word, it would have been an instant tip-off. Opisthotonos refers to a rigid body and bowed back. It was a classic sign of a kind of poisoning. How could King miss it?

Perhaps Spilsbury, the great man, would have figured it out. But then Spilsbury was not without weakness. After being knighted, the aging master left a Bunsen burner running in his lab, knocking himself unconscious. No pathologist would miss the clues. Official cause of death: coronary thrombosis brought on by carbon monoxide poisoning. Suicide.

It was four months from the time of Parvesh’s death before Dr. David King completed the final lines of his autopsy report, reaching for answers to the end, his conclusion left dangling like a question mark. He wrote, in part:

Summary of abnormal findings:

Postmortem examination revealed the body of a young-appearing, East Indian female showing no significant external abnormality. Internal examination showed oedema of the brain with evidence of herniation, but no subarachnoid or subdural hemorrhage and no other external evidence of the cause of the brain pathology....

Changes of very early acute bronchitis noted in the right lung. The heart was normal. No pulmonary emboli were present, microscopic examination revealed changes in the brain of early but established anoxic ischaemic encephalopathy but an underlying pathology was not identified. It is quite possible the collapse could have been due to some cerebral pathology but this could not be identified.

Cause of death:

1a) anoxic ischaemic encephalopathy due to

b)

collapse of unknown cause.

b)

collapse of unknown cause.

Parvesh Dhillon’s brain was sent off for incineration, meeting the same fate as her body already had. As a matter of protocol, King had tiny tissue samples from the brain and other organs sealed in paraffin wax, then packed in a series of thumbnail-sized blue-gray plastic cartridges and placed in a cardboard container the size of a box of chocolates. The case closed, a technician carried the box to a cramped storage room in the bowels of the hospital and put it on a shelf, squeezed between hundreds of other containers of tissue samples from other dead. That’s where the final traces of Parvesh Dhillon remained, in darkness, her secret, and her killer, still safe.

Other books

Brown Skin Blue by Belinda Jeffrey

Taming Her Heart by Marisa Chenery

Dormia by Jake Halpern

Back by Norah McClintock

Ginger Krinkles by Dee DeTarsio

Mate of the Dragon by Harmony Raines

Too Tempting to Resist by Cara Elliott

Dawn of the Mad by Huckabay, Brandon

Motown Breakdown (Motown Down #4) by K.S. Adkins

On Keeping Women by Hortense Calisher