Poison (52 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

Over time, Hamilton’s reputation as a Mafia city became more quaint than anything else. Had it ever been like the stories? Did bootlegger Rocco Perri really exist? Did he lie encased in concrete at the bottom of the harbour? Or was that a

Sopranos

repeat? The line between good and bad blurred. Papalia, “The Enforcer”—who spent nearly one-quarter of his 73 years behind bars for possession of drugs, breaking and entering, assault, conspiracy to import narcotics—was, according to the media, “respected and feared, the last of the city’s old-time godfathers.” It burned Korol.

Sopranos

repeat? The line between good and bad blurred. Papalia, “The Enforcer”—who spent nearly one-quarter of his 73 years behind bars for possession of drugs, breaking and entering, assault, conspiracy to import narcotics—was, according to the media, “respected and feared, the last of the city’s old-time godfathers.” It burned Korol.

For a cop, in homicide, there are few opportunities for closure. One case leads to the next, and the unsolved cases linger in the consciousness like tiny pieces of broken glass that every so often bare their edges. There are occasions, though, when the story really does end and justice seems black and white, perhaps even poetic. For Warren Korol, there was that one spring afternoon not too long ago, a Saturday, a moment independent of time, when his life seemed to come full circle. He was at home, a day off. Morning drizzle and fog lifted to reveal layers of cloud. He worked on his new backyard deck, wrestling with a machine he had rented

to burrow post holes in the soggy ground. His cellphone rang. It was Superintendent Bruce Elwood. Elwood got right to the point. There had been a shooting. A contract hit.

to burrow post holes in the soggy ground. His cellphone rang. It was Superintendent Bruce Elwood. Elwood got right to the point. There had been a shooting. A contract hit.

“Yeah?” Korol said curtly. “And?”

“And we need some help,” Elwood said. “Can you come in?” They needed someone to get to the morgue to officially check in the victim’s body.

“Bruce,” Korol said, unimpressed, the news not yet sinking in, “I’ve got this thing on the go. Got a post-hole auger machine here and it’s costing me money.”

But Korol agreed to go in. The personal significance of the shooting settled in as he changed clothes and slid his Glock into the shoulder holster, then drove to Hamilton General Hospital. Korol parked, entered the ER, walked up a hallway to the gurney where the body lay covered with a sheet. A police guard stood alongside.

Korol escorted the attendant wheeling the gurney down to the morgue in the basement. The gurney stopped. He pulled back the sheet. The propane-flame-blue eyes looked at the cold, lifeless, wrinkled face. Korol stared for a moment, making sure it was the man Elwood said it was supposed to be. It was indeed Johnny Papalia. Pops. The Enforcer. The old man had been in poor health. A bullet in the head didn’t help. The skin was bruised, the white sheets stained from the wound in the back of his head. A bullet of a particular caliber, when fired into the skull, actually moves around inside, striking the brain, until the energy of the projectile expires. And so the eyes were wide open, and black, as if dark marbles had replaced the irises.

The Mafia don had been shot execution-style in the left side of the head earlier that morning on Railway Street. Papalia had outlived many of the police officers who once pursued him—like Uncle Mike. Pops, the bad, and Pauloski, the good, were the focal point of the prized 1961 black and white photo that hung on the wall in Korol’s office. Uncle Mike had died in a car accident at the hands of a drunk driver on Upper James in 1967, a full 30 years before Papalia would roll in a hearse past hundreds of onlookers, denied official funeral rites by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Hamilton for his sins.

In the morgue, satisfied that the victim was indeed Papalia, following protocol, Korol took a Polaroid photo, filled out a proof-of-death form. It was the final chapter in the godfather’s life, a story in which his hero Uncle Mike wore a white hat 30 years earlier. The steel door opened, a sheet of cold air floated out. Korol pushed the gurney into the freezer, shut the door tight, taped it with an official seal. The routine over, it hit him. He was booking Pops into the morgue. The bastard who had tormented Uncle Mike, sent mock funeral wreaths to Aunt Sally, spread the word around town that Mike and Sally’s son would be kidnapped. The son of a bitch who had his people phone Sally late at night, when Mike was out on the job, whispering that Mike Pauloski was in the morgue. Well, now Papalia was in the morgue. And Korol was doing the honors. He reached for his cell.

“Aunt Sally? It’s Warren. How’re you doin’?” He grinned broadly. “You’ll never guess what I’m doing right now, Aunt Sally.” She had always been a feisty woman, and still was. She could tell something was up, but said nothing. “I’m puttin’ John Papalia in the morgue. I had to call. I bet Uncle Mike is looking down on me right now.”

“I don’t know what to say,” Sally replied. “Other than it’s about time.”

Warren Korol walked out of the hospital. The day was gray. He walked under the ceiling of cloud that faintly glowed silver with diffused light, the smell of damp grass and earth coming to life. A warm, firm wind tousled his hair.

Dhillon was not a practicing Sikh. If he had ever embraced Sikhism’s tenets, he had abandoned them early in his life. Born in northern India 500 years ago, the religion rejected the multiple gods and entrenched caste system of Hinduism. But both religions share a belief in reincarnation and karma. For Sikhs, the soul begins in God and the mission is for one’s soul to return to be with Him, while at death the body returns to the earth. The souls of those who live a noble life, or strive for it, may return to

God. The souls of those who live a dishonorable life will instead plunge back into the cycle of existence, the true hell on earth, reincarnated in a form other than human. The souls of the most evil people will end up in a snake, perhaps, or worse, a nonliving form. The cycle will repeat many times over until one day the soul is given another chance within a human being. True believers know where Sukhwinder Dhillon’s soul will go upon his death. The snake, certainly, or perhaps a stone, embedded in the cold earth, beyond light’s reach.

God. The souls of those who live a dishonorable life will instead plunge back into the cycle of existence, the true hell on earth, reincarnated in a form other than human. The souls of the most evil people will end up in a snake, perhaps, or worse, a nonliving form. The cycle will repeat many times over until one day the soul is given another chance within a human being. True believers know where Sukhwinder Dhillon’s soul will go upon his death. The snake, certainly, or perhaps a stone, embedded in the cold earth, beyond light’s reach.

As for the desired earthly destination for many Punjabi Sikhs, Canada remains coveted. That journey ended tragically for Parvesh Dhillon. But then the true believer knows her soul will take a much different route than her husband’s. Parvesh’s story on earth came to an end in the Punjab one day not long after her death, at Kiratpur Sahib on the warm, emerald-green waters of the Sutlej River. The Sutlej is where the last rites of the three Sikh gurus were once performed, and Kiratpur Sahib is, along with the Golden Temple in Amritsar, the holiest of places for Sikhs, the place where the ashes of their dead are brought. Sikhs reverently visit the white temple there, and the watery resting place for the ashes of their people. Parvesh’s parents brought her ashes here. As it happened, both of them were less than two years from their own final trip to the river; their daughter’s sudden death had sapped their life force.

Had Parvesh never left the Punjab, she might have lived to old age, her green-blue eyes watching her children grow, witnessing the tug of war between old customs and the modern world. And, had she lived and died in India, her body would have burned in a traditional funeral pyre, flames igniting the banyan and ashok logs stacked around her. The heat of the pyre would not have been nearly as intense as that of a modern crematory oven, and there would have been no mechanized pulverizing of the bones afterward.

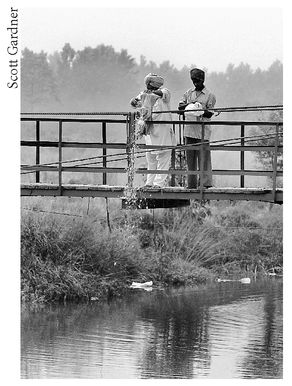

After a traditional cremation, family members go to the Sutlej. The first bag, containing chunks of bone, is emptied into the water, splashing rudely. From the second bag come the charred ashes, coarse bunches of them. But Parvesh had made it to Canada, the land of the golden dream. She had the benefit of a Western cremation.

The Sutlej River at Kiratpur Sahib

And so, from the low bridge at Kiratpur Sahib, her father opened the bag, allowing fine, pale ash to float down, dotting the water like raindrops, or touching the surface with the gentleness of rose petals, then floating slowly downstream. If God truly wrote Parvesh’s story, that wasn’t the end, not quite. The tiniest particles paused in the thick air, then whisked into another dimension of time and space by tropical winds, east over Chandigarh. They floated up higher still, into the dry air and blue skies of the Himalayan foothills that ring her homeland, over the rolling green ridges and silver waterfalls near Simla, before finally descending again onto the trees below, to be stirred on occasion when the breeze blew strong.

EPILOGUE

March 2008

Hamilton, Ont.

Hamilton, Ont.

Warren Korol strode along King Street downtown, trench coat collar turned against a cold wind. Years back as a young uniformed cop, Korol drank coffee all day, then one day, tired of the habit, ripped the lifeline out, quit cold turkey for years. Today he stepped into the Jet Café and ordered a cup.

He had been 35 years old when he started chasing Dhillon as a detective and was now 47, had marked his birthday a few weeks earlier. Even with 50 in his sights, he was far from the picture of a jaded, faded cop. The hair had grayed but was still full, Korol kept it tight on the sides, short on top. The blue eyes were framed by a smooth face that defied the years, and he had dropped several pounds to 215 since getting into serious running. Planned to enter his first 30-km Around the Bay road race in Hamilton, followed by a longer marathon in Ottawa.

“I’m still in the Clydesdale class,” he said with a grin. “We’re not breakin’ any records or anything. But running has done a lot for me.”

He is now Inspector Warren Korol, has held that title with Hamilton Police for five years. The last two he’s worked as chief executive officer in the office of the chief. Korol has enjoyed the post, but misses investigative work, hoped to return to more of it in the spring when he was to be moved to a position as inspector with the downtown patrol branch. While his professional life moved ahead at a brisk clip after sending Dhillon to prison, his personal life has not always been tidy. But through it all his greatest source of pride remains maximizing time with his children, working together with ex-wife, Charlayne, to bring them up. The pair are often seen sitting together at their kids’ ball games.

Korol took a sip of his coffee, thought more about the bond he and Charlayne share, and the kids—and this is the one thing that gets to him, the ice under his skin melting now, face flushing, eyes tearing. Anything to do with the kids, he can’t help it, it chokes

him up. He paused a long while, gathering his composure. “We continue to care about one another. Our number-one thought is raising our children.”

him up. He paused a long while, gathering his composure. “We continue to care about one another. Our number-one thought is raising our children.”

The Dhillon investigation, and the media attention from his role in it, did little to hurt Warren Korol’s rise in the police service. It was the case of a lifetime and, no matter what he does, the experience will always stand out in his career. It was also a high point for his old partner, Kevin Dhinsa. But for Dhinsa, the road after was not nearly as smooth.

Dhinsa was convicted of drunk driving in 2003 and was demoted. And then, later, 12 women—11 officers and one civilian employee—filed workplace harassment allegations against him. As of March 2008, he was suspended without pay because of that controversy. None of it, of course, alters what Dhinsa accomplished in the Dhillon investigation. When Dhillon’s second and final murder conviction was announced in court, there was one name the killer took in vain: Dhinsa. He had played a crucial role in the case, and a difficult one. From the beginning, he was the one who couldn’t dissociate himself from it entirely, leave it at work. As a member of Hamilton’s Sikh community, dealing with witnesses, some of whom knew members of his own family, it was a difficult situation, especially early on. He received threatening phone calls. Dhinsa handled it all with courage and grace. So much happened while justice ran its course. His father and sister died, his wife gave birth to a son. But at the end of it all, Dhinsa took great pride in helping lock Dhillon up.

Another player involved in the Dhillon investigation who met with far more controversy was Dr. Charles Smith. The man who exhumed Dhillon’s dead twin sons in India, a once-renowned pediatric forensic pathologist, had his reputation taken to the woodshed at a public enquiry, where it was learned that he had botched 20 death investigations, sometimes resulting in false convictions. As it happened, his work on the exhumation of the twins was not part of that inquiry, and Dhillon’s alleged murder of those babies never made it to court. For Brent Bentham and Tony Leitch, the Crown attorneys who prosecuted Dhillon, that was probably a good thing. If the Crown had somehow hung part

of its case against Dhillon on the twins’ murders—and therefore Smith’s work—his subsequent disgrace would have been fuel for Dhillon’s appeal.

of its case against Dhillon on the twins’ murders—and therefore Smith’s work—his subsequent disgrace would have been fuel for Dhillon’s appeal.

Other books

Wicked Enchantment by Anya Bast

Sweet Serendipity by Pizzi, Jenna

Caught by Brandy Walker

Sex and the Citadel by Shereen El Feki

Dawn Endeavor 3: Julian's Jeopardy by Marie Harte

Sins of the Father by Angela Benson

The Elementals by Saundra Mitchell

All Note Long by Annabeth Albert

Carson Mach 1: The Atlantis Ship by A. C. Hadfield

On Any Given Sundae by Marilyn Brant