Pompeii (34 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

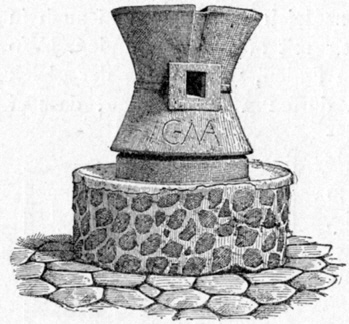

In the back part of this main room stood the flour mills. There were originally four of these, making this one of the larger bread-making establishments in the town. Pompeian mills followed the same standard plan, and were constructed out of stone quarried in northern Italy, near the modern town of Orvieto (a striking example of a specialised import, when presumably the local stone would have done an adequate, if not so good, job). It was a simple system in two parts (Ill. 65). Grain was poured into the upper, hollow stone, which was turned (using wooden struts and handles) against the fixed solid lower block – so as to grind the grain, which fell out as flour into the tray beneath. But at the time of the eruption in this bakery, only one of the mills was in working order with both its elements intact and in place. One of the upper pieces of the other mills had been smashed, and two were being used to hold the lime for the repairs and renovations that were going on.

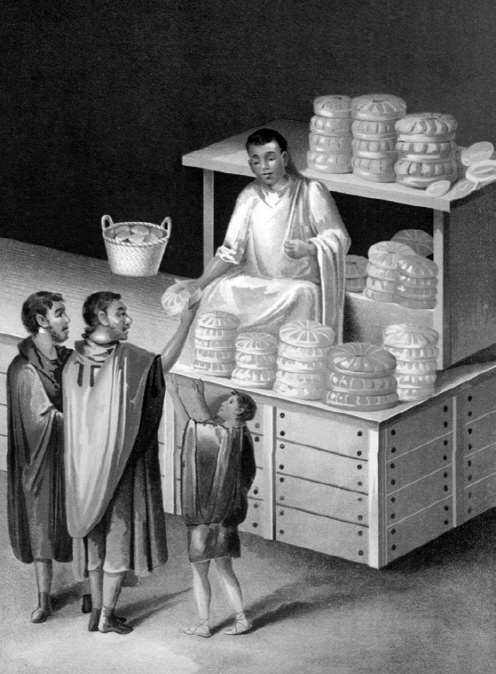

64. A bread stall – or perhaps a free handout financed by some local bigwig. This nineteenth-century copy of the original painting gives a good idea of the kind of wooden furniture and fittings that would originally have been found in shops or outside stalls. Often now it is only the nails, here very visible in the planks of the counter, that survive.

65. A flour mill. It would have been fitted with wooden struts (inserted into the square hole) – to enable the millstone to be turned by slave or mule labour.

How were the mills turned? By men or animals? Both are possible, but in this case we can be certain that the process was powered by mules, donkeys or small horses. The remains of two of these animals were actually discovered in the kneading room, where they must finally have been overwhelmed in an attempt to get out. Their stable had been, it seems, one of the rooms that opened into the milling area – a once much grander affair, with decent wall paintings, but later converted into an animal stall, complete with a manger. But these were not the only animals on the property. Five others were more securely penned up in another stable which opened onto the side alley. When first discovered, these were firmly identified – by traditional methods of bone classification – as four donkeys and a mule, of different ages ranging from four years to nine. More up-to-date analysis of the animals’ DNA has shown, however, that two were either horses or mules (bred from a female horse and male donkey) and three either donkeys or hinnies (the offspring of a male horse and female donkey). Animal recognition across the centuries is obviously harder than an amateur might imagine.

The skeletons of these animals in the second stable still remain exactly where they were found (Ill. 66), and one day when this property is finally opened to the public they will make a ghoulish display. But they have offered all kinds of glimpses into the life of the bakery and the world of Pompeii more generally. For a start, this number of animals makes it fairly certain that the reduced scale of the operations in the bakery was intended to be only temporary. You would not, after all, have hung on to seven of them, with all the expense of their upkeep, if you were permanently downsizing to a single mill. It also suggests that they were being used both for grinding the grain and for delivering the finished bread. And, unless the absence of any sign of a cart is to be explained by the fact that it had been used by the human occupants in their own escape bid, then they carried out these deliveries laden with baskets or panniers.

But more than this, the careful excavation of the stable has produced the first good evidence we have about the living conditions of the four- rather than two-legged residents of the town. The floor was hard, made out of a mixture of rubble and cement. Some light and air came in from a window looking onto the alley. A wooden manger ran down the long side, and there had been a drinking trough, though this seems to have collapsed before the eruption. The position of two of them suggests that they were tethered to the manger, though one was certainly untethered, or had broken free, for it seems to have been trying to escape through the alleyway door. They were living on a diet of oats and broad beans, which were stored in a loft above the stable. In other words, nothing was much different from how it would be today.

This bakery has sprung one further surprise. For the most part its other rooms are of modest size and decoration, and they presumably housed the baker, his family and slaves, upstairs and down. There was a small internal garden, which also functioned as a light well in what must otherwise have been a fairly dingy atmosphere – and where the slightly mangled remains of an ancient Roman fly were discovered (its exact species is still a matter of debate). And on the kitchen hearth the remains of a last meal were found: a bird of some sort and part of a wild boar had been left cooking. But the real surprise is the oversized and richly decorated dining room, with a large window looking onto the garden. Though out of commission at the time of the eruption (to judge from the pile of lime found there), it was painted with a series of alternating red and black panels, featuring at the centre of each of the three main walls a scene of drinking and banqueting, and couples reclining in each other’s arms (Plate 10). Compared with some Pompeian scenes of riotous sex, these seem rather decorous expressions of passion, and they have given the place its modern name: House of the Chaste Lovers.

66. This victim of the eruption reminds us how important animals were in the various trades of the town – driving machinery and delivering goods. They must also have contributed considerably to the dirt in the streets.

Why such a large

triclinium

in this modest bakery? Possibly, it was the baker’s one extravagance. But more likely it was another way in which he made money. Though not a restaurant in the modern sense of the word, this was probably a place where people paid to eat – with food either cooked in the kitchen adjacent or brought in from outside. It was not exactly glamorous surroundings. You would have reached the dining room either via the stable or by going past the bread oven and flour mills. But the room’s decor was elegant enough, and it could certainly have accommodated more people than could easily be squeezed into the average living quarters of the poor. It was probably not the only such arrangement in the town. In another house, a similarly oversized dining room is found together with a suspiciously large number of graffiti celebrating the fullers. Could this be, as some archaeologists have guessed, the place that the fullers hired for their communal evenings out?

When not in the midst of repairs, our baker was producing bread on a relatively large scale, and supplementing his income with a catering trade. Who he was, we do not know. We can, however, put a name to the next Pompeian tradesman we shall investigate: the ‘banker’ Lucius Caecilius Jucundus.

A banker

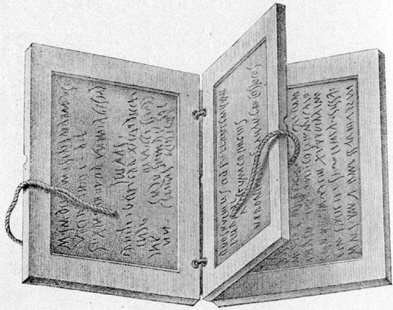

One of the most extraordinary discoveries in the history of the excavations of Pompeii was made in July 1875: 153 documents which had been stored away in a wooden box in the upper storey of the house now known as the House of Caecilius Jucundus. The main text in each case had originally been scratched into a wax coating over a wooden tablet, about 10 by 12 centimetres (often joined together to form a three-page document, with a summary in ink occasionally written directly onto the wood on the outer faces). The wax, needless to say, has disappeared, but the text remains legible, or partly so, because the metal writing tool or stylus had actually gone through the coating to mark the wood underneath.

All but one of the documents record financial transactions involving Lucius Caecilius Jucundus, between 27 CE and January 62 CE, just before the earthquake. The exception, the earliest text dated to 15 CE, involves a man called Lucius Caecilius Felix, who is probably Jucundus’ father or uncle. Most of the documents are to do with auctions that Jucundus has conducted: receipts in which the sellers of the goods concerned formally declare that Jucundus has paid what was due (i.e. the money raised by the sale, minus his own commission and other costs). Sixteen documents, however, deal with various contracts that Jucundus has with the local town council. We now tend to call Jucundus a ‘banker’, but the modern sense of that term hardly captures Jucundus’ role. He was a characteristically Roman combination of auctioneer, middleman and moneylender. He was, in fact, as the tablets make clear, profiting from both sides of the auction process – not only charging commission to the sellers, but also lending money at interest to the buyers to enable them to finance their purchases.

For the history of the Pompeian economy, these documents are a goldmine. They allow us to take a first-hand look at one Pompeian’s financial dealings – at what was being bought and sold, when and for how much. Besides, as the documents were witnessed by up to ten witnesses, they offer the most comprehensive register of Pompeian people that we have. Yet some words of warning are in order too. We do not know why the documents had been kept, what proportion of Jucundus’ business dealings between 27 and 62 they represented, or why these had been selected for keeping. Why for example the single document relating to Felix? Had it simply been kept for sentimental reasons as a memento of Jucundus’ predecessor? Why do the auction records cluster in the years 54–8, when the man had been in business since 27? And why do they stop in 62? Did he die in the earthquake as some modern scholars have wondered? Or were the more recent documents stored somewhere more convenient, not stashed away in the attic? One thing is certain. We do not have a complete picture of Jucundus’ activities for any period. What we have is only a selection of his filing cabinet, perhaps at random, or at least made on principles we cannot now reconstruct.

67. The tablets of Jucundus were originally fixed together in several leaves, the writing on the wax inside protected by the outer faces. This made them relatively easy to keep safe as a record of the transactions.

That said, it is wonderfully vivid material. The one document relating to Caecilius Felix concerns final payment for a mule auctioned by Felix for 520

sesterces

– and it is the key piece of evidence for the price of such animals in Pompeii. Here both seller and buyer were ex-slaves, and the buyer’s proceeds were not handed over to him by Felix himself, but by one of his slaves. Everything was sealed and dated, following the standard Roman system of calling the year after the two consuls in office at Rome itself: