Pompeii (41 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

Predictably enough, once we get below the level of the

ordo

the evidence is much thinner and it is even harder to pin down exactly what these groups did or how they were constituted, or just how ‘official’ they were. We can guess, for example, that there was some difference in status between the ‘cushion-sellers’ (if that is what they were) and the

forenses

. But what exactly? Some were even on the margins of legality. Tacitus explains that one of the Roman government’s responses to the riot in the Amphitheatre was to disband ‘the illegal clubs’. Which were these?

Murky as these groups are, however, the important point is not just that there were organisations in the town which involved those who would have been excluded from the

ordo

itself. It is also that they seem to have operated on similar principles to those of the local elite, and with sometimes similar rewards. Benefaction, for example, played an important role at this level too – whether statues or theatre renovation. Pompeii was a culture of

giving

, at all levels. Public office of any sort entailed public generosity.

Probably the most important of these groups were the

Augustales

, one of those associations that voted to honour Decimus Lucretius Valens, and which may almost have amounted to an

ordo

for ex-slaves. The evidence for this group in Pompeii itself is very fragmentary: we have plenty of evidence for its individual members, but little for what the

Augustales

as a whole did. Again our picture must depend on piecing together what we know from other towns in Italy. Their name makes it fairly clear they were involved with the religious worship of Augustus and later emperors, but they were not a specialised ‘priesthood’ in any narrow sense. For the most part, we find them engaged in sponsoring banquets and buildings, and even – like the

ordo

itself – paying an entrance fee to get into the group.

The large tomb monuments of some of those commemorated as

Augustales

in the cemeteries outside Pompeii suggest that they were individuals of wealth and power in the town. One in particular, the memorial to Caius Calventius Quietus (almost certainly an ex-slave), boasts that ‘on account of his generosity’ he had been awarded, ‘by the decision of the council and the agreement of the people’, a

bisellium

– a special, and specially honorific, seat in the theatre that was awarded to the city’s leading men (Ill. 72). What the Marcus Holconius Rufuses of the Pompeian world said about the likes of Caius Calventius Quietus we cannot now know. But in death at least there is nothing to distinguish him from the members of the oldest landed families. Fiercely hierarchical society though it was, the routes to prestige at Pompeii, even for those outside the decurial class, were more varied than they might seem at first glance.

72. This tomb of an ex-slave, erected as was usual alongside one of the roads leading out of the city, boasts of the civic honours won by Caius Calventius Quietus. In death it can be hard to distinguish the monuments of the old Pompeian aristocrats from those of the new rich.

But the biggest surprise in this male hierarchical world is to be found in the Forum itself. The largest building in the area, standing at the south-east corner, was erected in the reign of Augustus (Fig. 14, Ill. 73). Its function has long been a cause of controversy, like so many of the Forum buildings: market, slave market, multi-purpose hall? But its inspiration is clear. We have already seen that two of the statues on its façade were copied from the Forum of Augustus. The carved marble door frames, decorated with scrolls of acanthus, reflect the contemporary style of the capital, and are very close to those on another celebrated Augustan monument, the Altar of Peace. Some art historians have compared its conception to a huge portico erected in Rome by Augustus’ wife, the empress Livia.

73. The Building of Eumachia as it is shown on this detailed nineteenth-century model of the excavations, displayed in the Archaeological Museum in Naples. The Via dell’ Abbondanza runs along the right, the large open courtyard of Eumachia’s foundation is in the centre, the Forum colonnade is at the bottom.

That is a good comparison in more ways than one. For this building, known as the Building of Eumachia, was also sponsored by a woman. Inscriptions over the two entrances declared that Eumachia, who was a priestess in the town, daughter of one leading family and married into another, built it ‘in her own name and that of her son ... at her own expense’. Her statue stood at one end of the building (Ill. 74), paid for by the fullers (hence the fantasy that the whole building might be a cloth-workers’ hall). We know almost nothing about Eumachia, and can only guess at all the different circumstances that might lie behind her building of this monument, and the different degrees of active involvement she might have had in the planning and design. Most likely she was attempting to advance the career of her son. But one thing is certain: the finished product is stamped with her own name almost as firmly as the theatre is stamped with that of Holconius. Eumachia here represents a similar conduit for the culture of the capital to make its way to Pompeii. And Eumachia was not the only such female benefactor. An inscription found in the Forum makes it clear that another of the major buildings there was the work of another priestess, one Mamia.

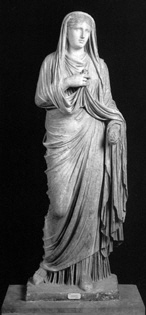

74. The statue of Eumachia from the building which she founded in the Forum. It is instructive for us to remember that this modestly clad figure could finance one of the largest buildings in the town.

We should not, for this reason, overestimate the degree of power held by women in this town. To be a priestess, public office though that was, was not the same as being

duumvir

. Even large-scale benefaction was a long way from formal power. That said, Eumachia is another example of the varied routes to public prominence the town offered. She is another ‘face of success’.

Dormice for starters?

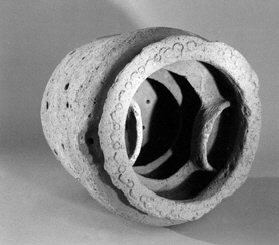

A curious pottery object, unearthed in the mid-1950s in a small house not far from the Amphitheatre in Pompeii, was almost instantly identified as a ‘dormouse-jar’ (Ill. 75). The idea is that the dormice lived inside, running up and down the spiralling tracks moulded into the sides of the jar (the Roman equivalent of a hamster’s wheel). A couple of feeding trays could be filled up from the outside, and a series of small holes let in air and a little light. For a lid was fitted on the top, to keep the creatures inside and, perhaps, to confuse their body-clocks with the constant gloom, so that they did not hibernate – although you might equally well predict that the dark would have sent them to sleep.

Unlikely as this reconstruction may seem, the strange pot does in fact match up almost exactly with a description offered by one first-century BCE writer on agriculture: ‘Dormice are fattened up in jars,’ he writes, ‘which a lot of people keep even inside their houses. The potters make them in a special shape. They make runs in their sides, and a basin for holding food. Into these jars, you put acorns or walnuts or chestnuts. When the lid is fitted, the animals grow fat in the dark.’ Several others have been found in Pompeii or round about. This leaves no doubt that a nice plump dormouse could be a delicacy of Roman cuisine. The one surviving Roman cookery book – a compilation of the fourth or fifth century CE, attributed to a well-known gourmet called Apicius, who lived centuries earlier and almost certainly had nothing whatsoever to do with the book – includes a recipe for stuffed dormice (‘Stuff dormice with pork stuffing and with the meat of whole dormice crushed with pepper, nuts,

silphium

[perhaps a kind of fennel] and fish sauce’). And at Trimalchio’s extravagant banquet that is the centrepiece of Petronius’ novel, the

Satyrica

, the starters included ‘dormice dipped in honey and sprinkled with poppy seeds’.

75. A Pompeian dormouse holder. Occasionally the Romans really did eat dormice, just as they do in the movies. They would have been placed in this small pottery jar (some 20 centimetres tall), with a lid – to be kept and fattened before consumption. The ridges in the side of the jar acted as exercise runs for the doomed creatures.

But these poor little creatures played a smaller role in Roman cookery than they do in modern fantasies about the luxury and excess of Roman eating habits, which are one of the most celebrated and mythologised of all aspects of Roman life. The lavish banquet at which men and women recline together in various states of undress, being fed grapes by battalions of slaves or tucking into silver platefuls of stuffed dormouse in

garum

, is a familiar image from sword-and-sandals movies and even TV documentaries. And the weirder aspects of Roman cuisine are regularly imitated at student toga parties and the occasional brave, if short-lived, modern restaurant (some concoction of anchovy usually standing in as a pale imitation of proper Roman fish sauce, and sugar mice doing duty for the real thing).

This chapter will explore a series of Pompeian pleasures, from eating and drinking to sex and bathing. We shall find (as the dormouse-holder has already shown) that the modern popular image of the Romans at play is not entirely wrong. But in each case the picture turns out to be more complicated and interesting than the hedonistic, excessive and raunchy stereotype implies.

You are what you eat

The Romans themselves had a hand in mythologising their eating and dining. The biographers of emperors made much of the ruler’s habits at table. Banquets were imagined as an occasion to enjoy his hospitality, but also to see the hierarchies of Roman culture sharply reinforced. True or not (and probably not), it was said of Elagabalus, a particularly strange third-century CE emperor, that he hosted colour-coded dinner parties (on one day all the food being green, on another blue) and that to make sure that the inferior guests knew their place he served them food of wood or wax, while he himself consumed the edible version. Other Roman writers discussed in minute detail the rules and conventions of elite dining. Should women recline with the men, or should they sit upright? Which position on the shared couch was most honorific? At what time was it polite to arrive at a dinner party? (Answer: neither first nor last, so it might be necessary to hang around outside to make a well-timed entrance.) In what order should the different dishes be eaten?