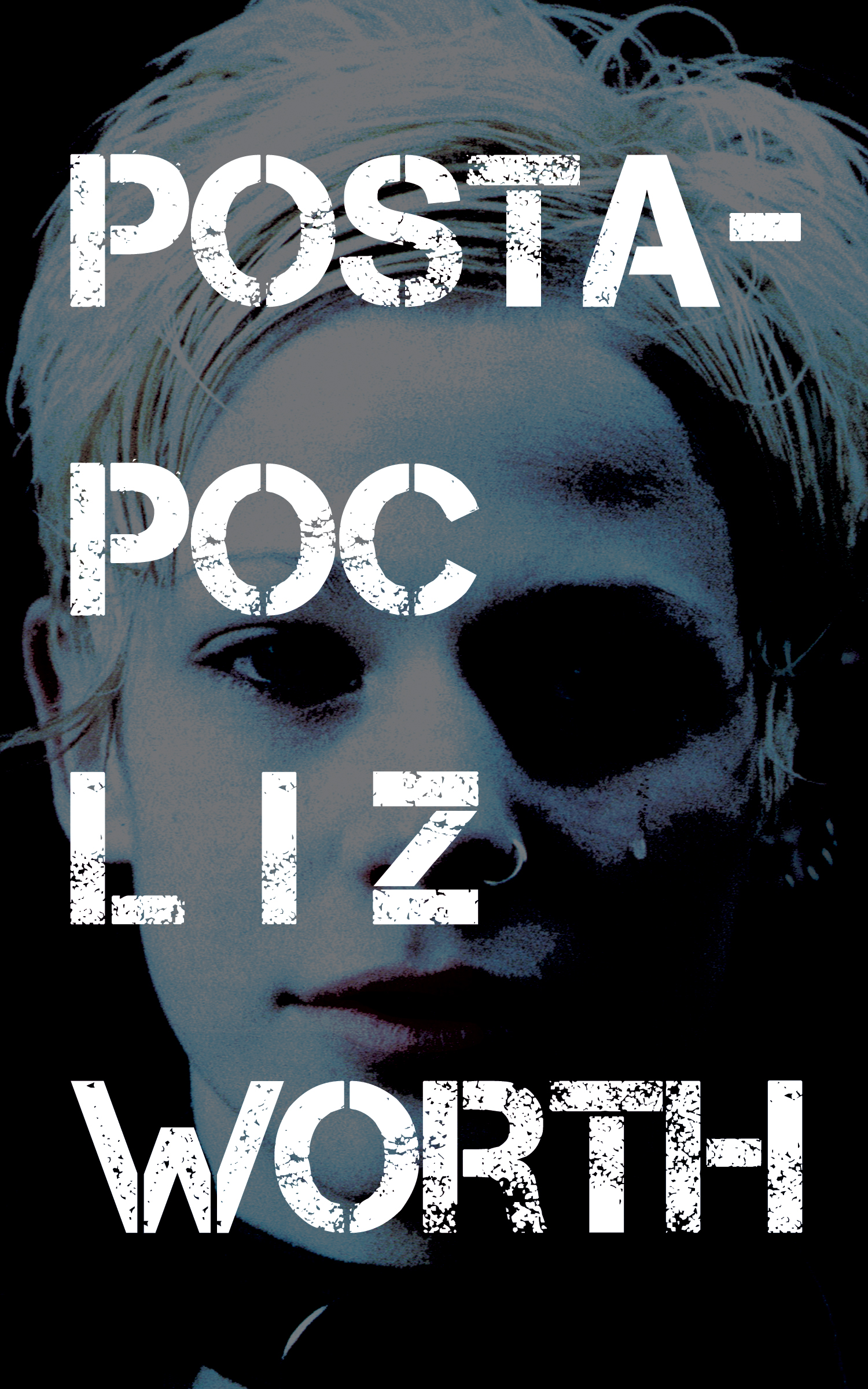

PostApoc

Authors: Liz Worth

POSTAPOC

“Whether it be poetry, performance art, or prose, Liz Worth has the uncanny ability to turn the grotesque and profane into something sublime and sensual. With

PostApoc

she has taken this to a higher level by solidifying her unique voice and bringing rock 'n roll to its logical dystopian conclusion.”

~ Brandon Pitts, author, playwright and poet

POSTAPOC

LIZ WORTH

Copyright © 2013 by Liz Worth

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced

in any manner whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publisher,

except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews.

Publisher's note: This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and

incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used

fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead

is entirely coincidental.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Worth, Liz, 1982â, author

PostApoc / Liz Worth.

ISBN 978â1â926942â29â2 (pbk.)

I. Title.

PS8645.O767P68 2013 C

813'.6 C2013â903636â9

Printed and bound in Canada on 100% recycled paper.

eBook development:

WildElement.ca

Now Or Never Publishing

#1101, 1003 Pacific Street

Vancouver, British Columbia

Canada V6E 4P2

Fighting Words.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council

for the Arts for our publishing program.

for nightmares

CONTENTS

- 1 -

OPEN UP AND START

O

utside, the dogs have all gone wild. Can you hear them? Can you feel them down there, voices shaking through loose skin?

At night their jowls fill with thunder. The howling is like wind wringing out hollow moans from the peaks of their spines, a chill that crawls through all the cracks in the windows.

The first time I heard it I thought I'd never heard anything worse. But then I heard the chime of dog tags, ringing beneath lupine shudders. Some of those dogs down there still have their collars on even though they have no homes, no owners anymore because those places, those people, they're all gone now.

So the dogs have all gone wild, reverting back to beasts that run on instinct instead of obedience. They can smell us from all the way up here, they're so hungry.

They've marked all the buildings on the block as their territory, bricks soaked so many times the smell's strong enough to climb the walls.

But those dogs, they don't know we're all starving, too.

Aimee, she's always saying we should do something to get rid of them. Poison or trap them. Wait till they starve and drive knives right between their ribs, plunge blades into their hearts and eat the beasts before they eat us.

But Cam keeps telling her no, says we need to keep the dogs around, that one day they could end up protecting us. He says that, right now, the dogs are all we have. Cam says a lot of things like that.

Before this all happened I thought the sky was going to open up and start spitting out animals. I thought the world would end in blood and hail, in bones and tiny bodies hitting the pavement until everything was pulp and fur.

But it started with the earth sucking all the moisture back into the ground and replacing it with a slow, quiet dread that hung over the city like a veil. It even sucked the water from our bodies, sweat beading along upper lips, leached to the surface by magnetic fields.

The day the drought finally broke, the sky brought down splotches of red, crimson breaking loose from the heavy velvet of clouds gone grey, drops drying to rust on the sidewalks everywhere, like old gum. Anyone caught in the chemical storm melted, just disappeared except for small puddles of sludge and sinew here and there.

But there was more to it than that, of course.

There was that day when all those people's chests imploded. It was in the thick of summer and all the girls had cut their hair or pulled it up into big ponytails, kept it tucked into bandanas or thrift store scarves. It was just too hot to have anything shading your neck, not just that summer, actually, but that whole year.

We only knew one person with air conditioning, so all of our friends invited themselves over to one apartment to get blasted with cold and blasted in every other way, too. That's where I was the day a neighbour from upstairs hopped down the fire escape and told us she'd just seen it herself, walking home along King Street: men and women with chests caved in, blood soaking through thin summer fabrics and eyes filmy and red.

We were never the kind of people who would watch the news, but we did that night, and heard about all this happening in Austin, Tokyo, Berlin, Calcutta, Sydney, Morroco and everywhere else.

I'm pretty sure the taste of my beer changed then, got mixed up with the sweat bubbling up on my lip as I chugged back everything I could swallow, trying to focus on the sound of liquid working behind my ears, pounding it all back as hard as I could to keep any more words from getting into me.

It didn't work, though. No matter what I did, I heard way more than I ever wanted to.

But if anyone thinks it was hard in those days to block anything out, it's nothing compared to how quiet it can get now.

I'm pretty sure it was longer, but it felt like it was just a few months after Aimee and I were in the Market, late afternoon heat gnawing at the backs of our calves. A shadow of smog had covered every city on the continent with a permanent grey, though the sun still fired with a precision focus that cut through the shrouded slabs of sky.

We'd been hearing about molecular shifts, not here but in other cities. It was in New York, Oslo, Stockholm where there were pockets of nothingâspace, airâthat people walked through and turned to mist, their bodies and bones disintegrating, nothing left but a suspended eyelid or a black speck of pupil.

Scarcity was a new word we were all starting to learn. By then there was a habitual hunger that had us reaching into fruit stands when no one was looking, moving fast through gawking tourists whose optimism seemed almost endless, our bags bulging with stolen apples and pints of strawberries.

In the park I reached into the pocket of my army cutoffs but withdrew my hand quickly with the confusion of a sting, my middle finger slit straight down the middle.

Aimee reached, tore back the flap of my cargo pocket and jiggled until the apple rolled onto the grass. That's when we saw the blade of its stem, the spikes at its base, things we were sure hadn't been there when we'd been dipping our hands into fruit baskets minutes before.

We'd been hearing about food turning to stones, pebbles, in people's mouths. But until then these were all just stories we'd heardâparanoia running wild. Now it was happening to us, my blood real and dark and smeared across the pocket of my shorts.

And I had to try hard not to cry then, even though I wanted to, badly, because that was the day that everything really started to feel too contaminated, like something new was creeping in close, closer, breathing hot darkness against our faces.

All through that year a strange heat had been seeping in slow and low to the ground, turning this city into a body swarmed by flies and clothed in soot that never seemed to exhale long enough to even offer us a sigh of wind.

The walls of buildings would sweat and the roaches in everyone's apartments had grown, thrived. Whole streets of trees bent at the trunks, their bark blackening.

All through that year we tried to remember the last time we had anything we could call a season, and all kept wondering: when did this really start? What was the first moment, the first incident? Was it last year, when summer stretched into November? Was it when all those birds fell from the sky somewhere in Nashville? Did the chemical rain or personal implosions only mean it was already too late?

When did we start thinking of it as The End, pronouncing it with capital letters, somehow making it official?

There were a lot of questions. There was a lot of wondering. We used to wonder about this sort of thing a lot.

We don't wonder about it so much anymore.

- 2 -

SISTERHOOD

E

xcept that's not really true, what I just told you. About wondering. Maybe that part about “we,” but I didn't say whether that includes me. It doesn't. Because this thing happened a long while back. This thing that turned me into a held breath, kept my hands shaking for asylum.

People used to see me a certain way. I was a girl who got noticed. Untouchable. Someone people thought they'd never be friends with.

But I'd left town for a while and came back half-dead. A downward spiral bored through my head.

As the sole survivor of a suicide pact I was reduced to panhandling outside of the Mission, just to be able to get in to see a show. I'd grown up in that club, but after I'd left they didn't know how to fit my name on the guest list anymore. There was no glory for the girl who couldn't break on through to the suicide.

The Vapids were playing the night I met Aimee. I'd spent a few hours outside before the doors opened, hands out and an eye on the layers of charms at my neck and wrists. I believed they couldâwouldâbring me luck, power, persuasion. Healing. They clicked at my pulse points, dogs' nails on a hardwood floor.

And maybe I did have some luck that night, because I made enough money to get into the show and enough to buy something extra to dip into.

I don't know how much time passed between getting inside and getting high, but I don't think it was long before I was a writhing OD on the Mission bathroom floor. Later, I'd asked Aimee what it looked like.

“I'd never seen that happen before. The skin. You'd think it'd be hot, flushed. A sick exterior. But it's not. It's chill come alive, barely.”

I was disappointed. It sounded the same as what I'd seen in others, a look I'd learned between sets when Valium were still playing, still alive. We all liked to tease our bodies to a metronome brink in those days. It was what the cult of the music dictated.

At that Vapids show, though, I hadn't planned on taking it very far. Hadn't expected the shit to hit me so hard, so fast.

In the bathroom the ceiling was fogged with pot smoke. I couldn't see anyone's faces but I knew other girls were around. I could hear their shrieking laughter. I tried to talk but my mouth was broken. All I could do was sink deeper into the base of the old velour couch, something that once would have been expensive, plush, now balding trash against a toilet stall. My eyes spun, pinwheeled. A silver spool of saliva tore out of the side of my mouth.

And then I was suddenly light enough to fit across a pair of arms. My shallow bones. I could hear the straw of my hair against skin, my head a bleached explosion at the inside of an elbow. I could smell myself.

The same white Smiths t-shirt I always wore stained with a dozen other nights. Its blooms of sweat released below the nose.

Aimee kept me floating by asking me questions: what did you take/who did you get it from/where do you live/do you want to go home or to the hospital/do you remember what you did earlier today/do you remember who you are?

Not that I had to tell her my name. She already knew. “I've seen you around before,” she said. “You're Ang. You're Ang. You're Ang.” She said it for me, in case I didn't know it anymore. She recognized me, the way I believed people still should, or would, even though I'd chopped my hair from waist-length to boy-short, bleached it from black to bare-bulb white. My weight had stayed off, though, cheekbones and chin still sharp, jutting.

I could never remember this part, but Aimee told me later I threw up in the sink as soon as we got to my place. Light purple pulp and cigarette ash in the shared bathroom at the end of the hall.

I kept the door to my room unlocked, having lost my key a month before and not bothered to ask for a replacement. I had nothing left that I cared about anywayâthe life lesson of depression.

My bed filled most of the apartment because the place was really just a room with a closet. Every other inch of it was covered in plaid shirts and bras, a rough pair of jeans I'd stolen and never worn. With the sleeve of her flannel shirt, Aimee wiped the residue from around my mouth and cleared a space on the floor all in the same motion.

She pulled me down and I pulled a piece of chalk off the windowsill behind her and drew a circle on the floor. I slid a ring off my finger and dropped it into the circle's center, pronounced us blood sisters. She accepted my sisterhood. For weeks after I would ask her to tell me this story, over and over, as affirmation that someone wanted me close, that someone had wanted to save me.

Aimee stayed with me for a while after that. I didn't own a blanket, relied only on the clothes piled on the mattress to keep us covered.

Aimee said she hardly slept at all whenever she stayed over. She learned early on that I lacked margins when I slept, a desiccated portrait.

The remains of my past were fossilized on the bedroom walls. Above us a suicide scene played out, all the way from the west coast. The room spat Polaroids and memories in negative images, a high contrast inversion in frosted blues to match the lips of my dead boyfriend, his dead friends.

The story always ended the same, with me being the only one to walk away.

That's where that story ended, and my question of responsibility began: was that the first moment, the first incident that jarred the universe off its course?

Did we lose the first rhythm because I didn't die that day? I can't even remember what dropped off in the beginning: the rush of mornings, maybe. Traffic and alarm clocks and packed subway trains. Not that I ever had a job to go to. Or a routine to maintain.

If I'd died that day, would we still have the rhythm of the seasons? We lost the silk of leaf on leaf in spring wind. We lost the colour green and forgot that branches used to be something more than spider-long fingers that snap in frail air. We lost the stop and start of red lights, green lights, and the caution of yellow. We lost caution. We lost birds at dawn and bus schedules and daily newspapers, the timing of rain after a storm's first thunderclap and any predictable rise of the sun. We lost, and we lost, and we lost.

And as we lost, people wondered not only where it started, but how, and why. Was it pollution? Germ warfare? Greed? God?

And as they wondered, my conviction grew, intuition tracing everything back to that one day when the knife didn't go deep enough, and I thought then that I knew the answer.