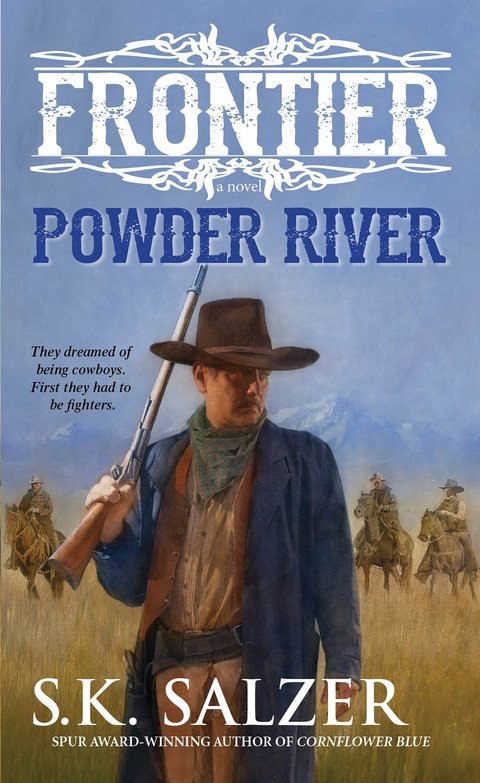

Powder River

Authors: S.K. Salzer

FRONTIER P

OWDER

R

IVER

OWDER

R

IVER

S. K. S

ALZER

ALZER

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Rose

Biwi

Lorna and Caleb

Lorna

Frank Canton

Harry

Dixon

Frank Canton

Odalie

Billy Sun

Dixon

Billy Sun

Dixon

Odalie

Billy Sun

Dixon

Billy Sun

Odalie

Billy Sun

Billy Sun

Odalie

Billy Sun

Lorna

Odalie

Dixon

Billy Sun

Odalie

Jack Reshaw

Jack Reshaw

Red Angus

Odalie

Billy Sun

Lorna

Odalie

Billy Sun

Frank Canton

Odalie

Billy Sun

Odalie

Lorna

Billy Sun

Odalie

Billy Sun

Odalie

Richard Faucett

Dixon

Billy Sun

Copyright Page

Dedication

Rose

Biwi

Lorna and Caleb

Lorna

Frank Canton

Harry

Dixon

Frank Canton

Odalie

Billy Sun

Dixon

Billy Sun

Dixon

Odalie

Billy Sun

Dixon

Billy Sun

Odalie

Billy Sun

Billy Sun

Odalie

Billy Sun

Lorna

Odalie

Dixon

Billy Sun

Odalie

Jack Reshaw

Jack Reshaw

Red Angus

Odalie

Billy Sun

Lorna

Odalie

Billy Sun

Frank Canton

Odalie

Billy Sun

Odalie

Lorna

Billy Sun

Odalie

Billy Sun

Odalie

Richard Faucett

Dixon

Billy Sun

Copyright Page

For Karen King Silvoso, sister and best friend

Rose

April 1870, Paradise Valley, Montana Territory

Â

Her last morning began like any other. Rose woke before dawn but remained in bed, eyes closed, listening to the familiar, comfortable sounds. She heard baby Harry's rhythmic breathing from his crib, the dog's soft, wet snore from his nest of blankets on the floor, the cheerful chirrup of spring peepers by the creek. A cool breeze, smelling of damp earth, stirred the curtains made of fabric she intended for a dress but repurposed when she realized the color no longer suited her complexion. Yellow used to flatter her, but no more. Her skin was darker and her auburn hair several shades lighter than it had been back in Missouri. She smiled to wonder, as she had many times before, if the home folks would know her if she passed them today on the streets of St. Louis.

She rolled onto her side, her face to the window, and wished the peaceful interval could last. Rose was tired all the time; she woke up tired. This was understandable, she told herself, given her condition, but her fatigue seemed different, more crushing and unlike the last time. She cherished these few minutes of quiet she had all to herself before the day's work bore down on her.

But now it was over. Rose threw back the gray wool army blanket she and Daniel still used, with U.S. stamped in black, blocky letters in the center, even though her husband's time as an army surgeon was years behind them. The spring morning was cold, and she wrapped her wool shawl around her shoulders as she tiptoed to the kitchen to light a fire in the new, cast iron cook stove squatting malevolently in the corner. Rose hated the thing. Two weeks before, she and Daniel had had one of their rare arguments when he and Billy Sun carted the stove home from Bozeman in the spring wagon. Dan had wanted to surprise her, and he did.

“It has a separate âauxiliary air chamber' just for baking bread,” he said, proudly pointing to said feature. “It's the newest model. Nick Stono says all the women back East have one. You'll be the first in Montana Territory.”

“Nick Stono says that, does he?” Rose said, folding her arms across her chest. The fast-talking merchant was famous for convincing people to buy items they didn't want or need, and her husband, she suspected, had fallen victim. “Really, Dan, I wish you'd asked me first. I don't want this. I'm happy with my old Reliance.” It had taken Rose a long time to make friends with the quirky little cooker she had used since she first went to housekeeping four years before at Fort Phil Kearny. It had involved much trial and error, many cakes and biscuits had been reduced to blackened lumps of charcoal, but now she and it understood each other. Rose was not keen to start all over.

“Return it and get our money back,” she said. “I want you to.”

Daniel's face fell so dramatically Rose almost laughed. “Now, Rose, honey,” he said, “don't be like that. It took Billy and me the whole day to get it here.” He and the Indian boy exchanged a look that spoke of shared misery. “You can't imagine how heavy that thing is. Just give it a try, will you, love? Just try it?”

In the end Rose relented, for she could never deny Daniel anything he asked of her, but she was annoyed. Learning a new stove added a good deal of work at a time when she already had plenty. It also galled her to think of how much Dan must have paid when there were so many other things she would have rather had, what with the new baby coming. They could have added a new room on to their two-room cabin. The space would be desperately needed, with two young children in the house. And they desperately needed furniture. Dan didn't know it, but she longed for a proper dresser with a marble top and a mirror large enough to show more than only her head and shoulders when she dressed for the day.

With a sigh, she opened the oven door and tossed wood from the box onto the glowing embers. At least the thing threw good heat. Bob was waiting at the door to go out and Rose obliged him, then ladled water from the barrel into a kettle and put it on the stovetop to boil. She did not put a match to the coal oil lamp, preferring instead the ambient light from the window. The sun was rising behind the snow-covered Absarokas, coloring the sky in glowing bands of pink and gold. It was a sight she never tired of, and the setting of the sun behind the Gallatin Range was equally glorious. How lucky she and Daniel had been to find a home in this beautiful valley, a place the Indians named Valley of the Flowers. Yes, they'd been fortunate in this as in so many things, and so far this spring, they'd been lucky in the weather, too. Not as much rain as usual and warmer days as well. Rose hoped the warmth would continue today for she had piles of clothes, whites and darks, in need of washing.

Bob was scratching at the door. After letting him in, she poured steaming water into a pan over the roasted coffee beans she'd ground the night before, stirred the mixture with a fork, and let it steep for three minutesâno more, no less. When the grounds were fully settled she poured the aromatic brew through a fine mesh strainer and into her blue tin mug. Daniel liked his with cream and sugar, but Rose took her coffee strong and black.

As she walked to the table, she felt a tightening sensation across her abdomen. She'd been having mild contractions for weeks, but this one, though not painful, was stronger than the others. She sat and sipped her coffee, fighting down faint stirrings of fear. She'd had similar sensations during her pregnancy with Harry, but not this soon. The new baby's time was at least seven or eight weeks distant. She had not mentioned the contractions to Daniel, but he seemed a bit worried when they parted the day before.

“Are you sure it's all right for me to go?” He placed his hand, palm down, on her rounded stomach. “Those horses will probably still be there next month when Mrs. MacGill comes. Burgess knows I want them; he wouldn't let anyone else have the pair. Or I could send Billyâhe never turns down a chance to go to town.”

Billy Sun was their hired man, the lanky, green-eyed son of a Crow woman and a French fur trader. The Frenchman had been killed by a grizzly one week after his son's birth, fourteen years before. The woman's brothers tracked the bear and killed it, making a necklace of the giant animal's claws. Billy wore it every day.

“No,” Rose said, shaking her head, “you should go. It's not only the horses, there will be patients waiting for you in Bozeman, people who've come a long way. Don't worry about Harry and me, we'll be fine. Besides, it's only two days.”

Harry was beginning to stir in his crib. When she stood to go to him, the tightening came again, this time so strongly it took her breath. Rose closed her eyes and breathed deeply, exhaled, then inhaled again. Unable to walk, she sank onto the chair and wrapped her fingers around the hot mug. She hoped the warmth would relax her, but the contraction grew in intensity. Clenching her jaw, she prayed for the pain to pass. When at last it did, she raised the mug to her lips with a shaking hand. Usually her first cup of coffee brought her pleasure, but today it was bitter as bile.

Bob came to her, his nails clicking on the puncheon floor, and laid his blocky brown head in her lap. “We might be in trouble, Bob,” she said, stroking his velvety ears. His eyes never left her face.

Harry wailed from his crib, and Rose realized she had not started his breakfast. Well, she thought, he'll have to make do with a cup of warm milk and leftover biscuit. She hurried to fetch the fat baby from his bed, hoping he wouldn't try to climb down. The crib, a gift from Nelson Story and his wife, stood well above the floor, and a fall could break a bone. She'd meant to ask Daniel to lower it before he left.

“There's my baby man.” She took Harry in her arms and nuzzled his warm neck, breathing in his sweet, milky smell. With a happy gurgle, Harry settled into her arms. As she did every morning, Rose crossed to Daniel's shaving mirror and stood so Harry could see himself. “There,” she said, kissing him on his downy head. “See what a good boy looks like?”

At that moment Rose was gripped by a pain so searing she almost dropped him. She fought her way across the room to the bed and collapsed, with Harry still in her arms. He gave her a smile, thinking they were having a game.

Beads of sweat popped out on her forehead and upper lip, though the morning air was cool. Yes, she thought, this was definitely unlike her experience with Harry. Then, things had started slowly, with contractions that were painless for the first four or five hours of her labor. Although Harry was her first child, she had not been frightened but confident, arrogant even. After all, she thought, countless women have done this since the beginning of time, how hard could it be? Things went on longer than she expected, but still, Rose was unafraid. She had the calming knowledge that her physician husband was pacing in the other room, ready at any moment to lend his medical expertise, should it be necessary. Most reassuring of all, Helen MacGill, tall, white-haired, and confident, had been at her side, comforting her and telling her what to expect. The pain had been tolerable until the end, and then it was immediately forgotten when she held her howling, healthy eight-pound son in her arms. Although the birth had been uncomplicated, the experience had left her with a new respect for her gender.

Now everything was different. She knew the pain that was coming, and she was alone. Helen MacGill was not there to help and neither was Daniel. Could she bring this child into the world unassisted? Though her confinement was nearly two months away, she was already bigger than she had been with Harry at term. What would she do if the child were nine pounds or even ten? Rose felt a sick sense of dread. Every woman knew all too well what would happen to her and her baby if she could not deliver it. The unborn child was very active now, and Rose suspected he or she was responding to her fear and the racing of her heart. She had to take control, for both their sakes.

Harry was beginning to fuss and wriggle in her arms. He was adventurous these days, forever tottering around on stout, dimpled legs, and required constant watching for there were many ways a child could die in this rough country. Just a month before, Daniel had witnessed the death of a neighbor's ten-year-old daughter when she, in passing, playfully slapped the leg of her father's draft horse with her bonnet. A stockinged foot flashed out and the girl dropped like a stone, dead before Daniel and her father could reach her side.

Rose pulled Harry close and sang to him, hoping he would sleep again though she knew this was not likely. Her only hope was that Billy Sun would arrive soon. When he went to the barn and saw Suzy had not been milked and other morning tasks were undone, he would know something was wrong. Billy would come to the house and she could hand Harry over to him. But even as she imagined this she felt another pain building, growing power like an ocean wave. She told herself to be calm, to ride it out, but Harry would not cooperate. He struggled from her arms and climbed down from the bed. Rose watched him toddle around the room and then toward the kitchen where the hot, wicked stove was waiting.

“Harry,” she called, trying to make her voice sound normal, “Harry, come to Momma.” When he didn't respond she spoke to the dog, seated by her bed, his eyes on her face. “Bob,” she said, “bring Harry.” At once, the dog sprang to his feet and herded the baby back into her room. Gradually the contraction faded.

Gingerly, knowing she did not have much time before the next pain grabbed her, Rose got out of bed and opened the cedar chest at the foot. She smelled the clean scent of cedar and the green leaves of rosemary she packed with the clothes and blankets to keep them fresh, and recalled a happier time. The tiny linen garments Harry had worn and the cotton flannel blankets she had bundled him in were on top. She traced the decorative stitchery along the blankets' borders with her finger, remembering the anticipation and joy she felt doing the needlework on those cold winter nights as she and Daniel sat by the fire. Those had been peaceful evenings, warm and happy, and infused with a golden glow. How different the world seemed now.

She put the baby's things on a chair by her bed, then changed Harry's napkin and dressed him in warm clothing, with sturdy shoes, and carried him into the kitchen where she sat him in his high chair. She put a pan of water on to boil, knowing she would need it later. By now the sun was fully risen; Rose thought it must be seven o'clock or later. Where was Billy?

She took a biscuit from the tin and gave it to Harry who ate it hungrily. Next he would need his milk, which she kept in a cooler by the well. For this Rose would have to go outside. She took her shawl from the peg and wrapped it tightly around her shoulders. The dog followed her to the door, but she stopped him.

“Stay, Bob. Stay with Harry.” Reluctantly, he turned back to his charge. Rose stepped out in the morning sun, shielding her eyes as she looked to the barn, hoping to see Sugarfoot, Billy Sun's buckskin gelding, drinking from the trough. She was disappointed. Billy was never lateâwhy did he choose this day, of all days, to be delinquent?

The pain came again as she started to remove the well cover. She grabbed the planks, her knuckles whitening with the ferocity of her grip, and held her breath as the pain grew in intensity until reaching a searing crescendo and sensation of tearing that brought her to her knees in the dirt. Rose rolled onto her side, tucking her chin and drawing her knees upward as far as her belly would allow, until at last the muscles began to relax. She exhaled with a gasp.

“God in heaven,” she said to the child inside, her voice sounding small and tinny to her own ears. “What are we going to do?” Somehow she would have to save them both. As she lay on the ground she heard Harry's wails from the kitchen. He was still in his chair and she had to get to him before he fell.

Rose put her hands on the ground and pushed herself to a seated position. Her hair, still unbound from the night's sleep, fell about her face like a curtain so she did not see Billy riding up the graveled lane. When he saw Rose on the ground he put the spurs to his horse and came on at a gallop.

Other books

In Another Country by David Constantine

From Pharaoh's Hand by Cynthia Green

Waiting in Line for the New iPad by Max Sebastian

Persuasion (The Wild and Wanton Edition) by Micah Persell

At Long Last by DeRaj, N.R.

Our Song by Ashley Bodette

Daddy's by Hunter, Lindsay

Cat Deck the Halls by Shirley Rousseau Murphy

Deadline by Maher, Stephen

Athenais by Lisa Hilton