Practically Perfect (3 page)

Read Practically Perfect Online

Authors: Dale Brawn

William found this mistreatment profoundly upsetting, and he talked to his sister-in-law about what he should do. He later said that he “told Dora I would do something to him.” He left her with no doubt about what that would be. “Dora knew I was going to kill him.”

[7]

Which is precisely what William did.

On April 10, 1933, Dora and Annie decided to spend a couple of days visiting at the home of Annie’s father. After they left, siblings John, William, and Alexander Bahrey played cards with a neighbour. Eventually everyone went home, except William and his older brother. Before they parted, Alec told William that he needed beer bottles for the moonshine he was making, and he was going over to their bother-in-law’s farm to get some. It was about two kilometres away, and when Alexander headed out, William followed. As the elder brother entered a granary, William crept up to a nearby snow bank. When Alex stepped out with the bottles, William shot him with a .32-20 Winchester, a centre fire rifle used to kill small game. To be sure his brother was dead he climbed onto a haystack and shot him three more times. William left the body where it lay and went home. The next morning he returned, tied a piece of barbed wire to Alexander’s arm, and dragged his body to the top of the same stack he stood on a few hours earlier. Then, just as he had done five months before, he started a fire.

The owner of the haystack noticed it go up in flames, but he lived some distance away, and it was not until April 16 that he went out to the field to investigate. Before he got there his dog was already nosing around what remained of the stack. Lying in the middle of the huge mound were bones of what clearly was once a human being. Because he did not have a telephone of his own, it was the next morning before the farmer contacted the local justice of the peace, who in turn telephoned the police.

On their way to the scene a contingent of officers from the North Battleford detachment of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police got stuck in a mud hole, and by the time they showed up news of the gruesome discovery had spread. What little remained of the body was considerably disturbed. Scattered around the field were parts of a man’s overalls, braces, buttons, and bones. Included among the latter were parts of a skull, a human torso extending from the waist to the thighs, pelvic bones, some teeth, and numerous small bones. At the bottom of a half-metre pile of ashes investigators also found a short piece of barbed wire with a loop at one end. Lying near it were two shell casings.

William Bahrey brutally murdered both his brother and his brother-in-law. He was mentally challenged, although not sufficiently so to escape the noose. His lack of understanding of his circumstances can be seen in the letter he wrote seeking commutation of his death sentence. He wanted to be paroled from jail, he said, because he was “anxious to return to take care of my farm duties.”

William Bahrey brutally murdered both his brother and his brother-in-law. He was mentally challenged, although not sufficiently so to escape the noose. His lack of understanding of his circumstances can be seen in the letter he wrote seeking commutation of his death sentence. He wanted to be paroled from jail, he said, because he was “anxious to return to take care of my farm duties.”

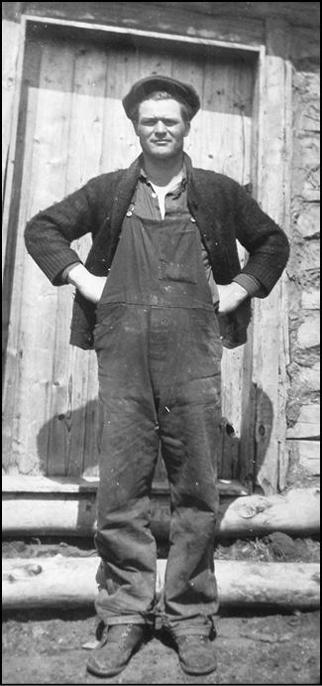

Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada.

After the remains were removed to a nearby church, the police encouraged people to view the body, in the hope that someone would see something that might help identify the person to whom the bones once belonged. Over the few days dozens of residents of the Whitlow district filed by, but many stayed away. John Bahrey was among the latter. He recalled being at home when his brother Harry stopped by. “We were talking about who it might be. It was said that it might be a tramp who had walked in there and slept in the straw pile.”

[8]

William listened to the conversation, but said nothing. After four days Ambrose could no longer put off what he must have suspected from the beginning: the body was almost certainly that of his son Alex, who had been missing for nearly a week.

Once the patriarch of the Bahrey clan identified the remains, the police quickly began questioning other family members. On April 19, they got around to William. He told them that the last time he saw Alexander, his brother was riding away from home on a bay saddle horse. A week later the horse was located, tied to a tree two kilometres from its owner’s homestead. It was obvious to investigators that in the preceding two weeks the animal had been well cared for.

The same day the police made their discovery, a coroner’s inquest was convened to look into the circumstances surrounding the death of Alexander Bahrey. After jurors finished examining the remains, the bones were sent to Regina to be examined by the province’s chief pathologist. She concluded that they belonged to “a fat, thick-set man of about 30 years of age and medium height.”

[9]

The short, chubby Alexander fit the description to a T. Even before investigators received the pathologist’s report, they concluded that if Alexander was murdered, his brother was the likely killer. In fact, from the time the police heard that Alexander was missing, officers kept William under surveillance. On April 25, they decided to increase the pressure on the Bahreys, and William was taken into custody on a coroner’s warrant. Even at this late stage had he said nothing, there was little chance William would have been charged with murder, and even less that he would be convicted. But a little over two weeks after being picked up, he told his jailors that he was ready to confess. What surprised the police was not that he was prepared to talk about his brother, but that he wanted to tell them about a second murder as well.

May 9, the day after he confessed to the killings, Bahrey led officers to the scene of both crimes. First he directed them to the haystack where he burned the body of his brother-in-law. There was not much left, although investigators found a quantity of small bones, a pair of cufflinks, and articles of clothing. It was not until more than four months later that the dead man’s skull was discovered a half kilometre away, and the remains were positively identified as those of Nestor Tereschuk.

From the haystack containing the bones of Nestor, William took his minders to the stream into which he threw the rifle he used to shoot his brother. Handed a rake, William went to the exact spot, and in no time pulled out the gun. After that he led the group to the gopher hole in which he stuffed Nestor’s cap. Next he walked to his brother’s farm. On the roof of a hen house officers found the dead man’s watch and razor, hidden there after he was murdered. Then William showed investigators where he was standing when he shot Nestor.

On May 11, Bahrey appeared at a preliminary hearing, called to determine if there was enough evidence to bind him over for trial. The result was a foregone conclusion, but Dora made the proceedings memorable. She had to be carried into the room, and as soon as she was sworn in, she became unresponsive to questioning, almost comatose. Then she suddenly she sat up, and in a loud, hoarse voice called out “Give me the Bible, swear me in a second time, and I will tell you all I know.”

[10]

With that she relapsed into her former state, and even questions posed by an obviously irate coroner did nothing to rouse her. Dora, however, was not to get off that easily. The police were aware that almost from the moment she learned that Alexander was murdered the grieving widow began living with her husband’s killer. The next day Dora was recalled to the stand, and this time she was ready to talk. In the opinion of many onlookers, her story could have come from a Tolstoy novel, delivered in broken English, and punctuated with a plethora of eastern-European idioms. The essence of what she had to say was crystal clear: William murdered both her husband and his brother-in-law.

Bahrey’s trial was scheduled to get underway the first week of October 1933, but before it did a specially empanelled jury was asked to determine whether the accused was mentally fit to stand trial. It was convened on October 2, and after deliberating for four hours, determined that William was sane enough to instruct counsel, and to appreciate the seriousness of what he was accused of doing. Bahrey’s trial started the next day. One Bahrey after another took the stand. None made any attempt to deny, or even minimize, what William did. On the seventh, Chief Justice James Thomas Brown imposed the only sentence he could: William Bahrey was to hang. The Saskatchewan Court of Appeal heard arguments about whether the condemned prisoner was sane enough to stand trial. The three-member panel reserved its decision, but when the judgment came down it confirmed that William must hang. On February 13, the Governor General, on the advice of the federal cabinet, turned down his request for clemency. The man who could not keep a secret was to be hanged ten days later.

Two days before that was to happen, Arthur Ellis, Canada’s busiest executioner, arrived in Prince Albert. He spent the next day making sure everything was in order, and just before 6:00 a.m. on February 23, 1934, Bahrey started on his last journey. Beside him, but ignored by the condemned killer, walked his spiritual adviser. William was hanged exactly as scheduled, and ten minutes later joined his two victims in the hereafter.

William Larocque and Emmanuel Lavictoire: Murders for Insurance

Fifty-seven-year-old William Larocque and his best friend and neighbour, fifty-one-year-old Emmanuel Lavictoire, were not subtle men. After they insured and murdered a young man who lived near them in southeastern Ontario, they realized they had a money-making scheme that worked. Their story is a saga of limitless greed, and illustrates how easy it was in the 1930s to get away with murder, at least for a while.

It all started with Athanase Lamarche. In October 1930, he drowned in a car accident while driving with Larocque and Lavictoire near Masson, Quebec. Shortly before his death, Larocque persuaded the dead man to take out a policy of life insurance, which paid double its face value if Lamarche were to die in an accident. Larocque and Lavictoire were the only witnesses to testify at the coroner’s inquest convened following the drowning, and the jury quickly concluded that Lamarche died as a result of an accident. Shortly after the father of Lamarche was paid by his son’s insurance company, Larocque and Lavictoire swindled him out of a large portion of the proceeds. The ease with which they were able to persuade their victim to insure himself, and then get away with killing him, seemed to inspire the two men.

Over the next several months they approached three other single men about insuring themselves. All refused to consider it, but when Larocque and his partner spoke to twenty-seven-year-old Léo Bergeron, the response was different. The young man supported himself by working for room and board, and was easily manipulated. He was, however, cautious enough to ask his father what he should do. The advice he got was blunt: “Don’t go in that. They will do with you the same as they did with Lamarche.”

[11]

A few weeks later Larocque showed up at the Bergeron farm, and said he was upset by what Leon said to his son, Léo. The father was unapologetic. He asked Larocque how much the policy cost. Told $55, he said his son could never afford it. Larocque insisted the issue was not money; it was about a smart business decision. “Larocque told me that Leo had no home and if he broke an arm or became ill he would be looked after. I insisted that Leo should not take out the policy. I did all I could to stop him, but after seeing that it was hopeless, I told Leo he could do as he pleased.”

[12]

When Léo was finally persuaded to buy the insurance, proceeds of the $2,500 policy were to be paid to his father, and if Léo died in an accident, the amount paid out would be double what his life was insured for. In early December 1931, Larocque made arrangements, presumably with Léo’s consent, to have the value of the policy increased to $5,000, and he replaced the insured’s father as sole beneficiary. Around the same time Lavictoire, who knew Bergeron only casually, tried to persuade the young man to take out a second policy of insurance, with Lavictoire as beneficiary. This time Léo refused. A little later Larocque asked an acquaintance cutting ice on the Ottawa River to hire Bergeron for the winter, but the man refused to consider it, suggesting the job was far too dangerous for a novice. The following month Léo was killed in an accident on Larocque’s farm.

The day before the incident Larocque made arrangements for Léo to help him with some harvesting. For a reason never explained he wanted Léo to start work at 8:00 a.m., although everyone else hired for the day was told to show up at noon. Bergeron’s first job of the morning was backing a team of horses into Larocque’s barn. Something spooked the animals, and as Larocque and Lavictoire looked on, Léo was trampled to death. At least that is the story the two men told on March 18, 1932. No one believed it — not the doctor who first arrived on the scene, not the police who followed, and certainly not the dead man’s father, who rushed to the Larocque farm as soon as he heard that his son was hurt.

When Leon Bergeron arrived, Léo was lying on the barn floor, a buffalo robe covering his face. The distraught father immediately removed it, and as he did so he saw his son gasp for breath, and then stop breathing. Bergeron was devastated, but he was also angry, and he confronted Larocque. The farmer told the grief-stricken father that his son’s death was an accident, that he was trampled after being knocked down by the horses. Bergeron said he did not believe it. He was certain Larocque murdered his son, just as he had Lamarche. Larocque told Bergeron that that was an odd thing to say: “It’s queer. I never heard anything about it.”

[13]