Prime Time (40 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

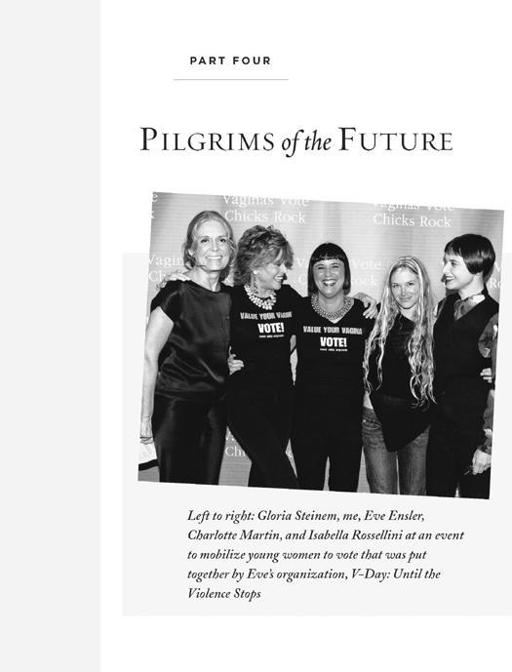

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

Mary Madden wasn’t alone in finding it hard to tell a man she wasn’t interested. “You feel kind of sorry for them,” she said. “A Vietnam veteran emailed me one day because he’d spent the whole day at the VA hospital because he could not hear and he could not walk. I was like, this is just not going to work for me. But it was hard. It pulls on a lot of heartstrings.”

My heartstrings got pulled in the Third Act just when I felt certain I didn’t care anymore and wasn’t looking. Five days before I was going to have knee surgery, I was in Paris shooting (in French and English!) a commercial for L’Oréal skin-care products for older women. A pal of mine, the wonderfully funny writer Carrie Fisher, sent me an email to let me know that a longtime friend of hers, the music producer Richard Perry, upon discovering that I would be stuck in Los Angeles for at least a month because of the surgery, had asked her to organize a dinner where he could reconnect with me. I had first met him thirty-five years earlier, when he brought together a group of music industry heavyweights in his home to support my then husband, Tom Hayden, in his campaign for the U.S. Senate. I remembered the house, perched atop a hill overlooking all of Los Angeles, with a pool and a tennis court and tastefully decorated in an Art Deco style. (He still lives there … and now so do I, much of the time.)

Ten years later we ran into each other at a party in Aspen. Tom had chosen to stay home with the children, so I arrived alone, and when I saw Richard I asked him to be my date for the evening. We danced together all night; and I didn’t see him again for twenty-five years. But there was that distant memory. And there were the songs he produced, hit after hit. Many of them I would use in the Workout classes I taught. I guess “Slow Hand,” by the Pointer Sisters, was the one that always made me wonder what Richard was up to. I have to tell you, when I saw his name in Carrie’s email, my heart did a little flip. I showed the email to Matthew Shields, my hairstylist. “See this name? Richard Perry? This could be fun.” Barely ten days after the surgery, when I was still on crutches, we had our “reunion” dinner, and he’s been my honey ever since. At seventy-one it felt good to feel good again and also to know that I can remain who I am, not trying to tailor my personhood to meet a man’s fancy—well, maybe a little. When we’ve grown up (and that took a while for me), we are clearer about who we are, what we want and don’t want, and this can mean that later in life the unexpected can always happen—if we remain open to it.

CHAPTER 16

Generativity: Leaving Footprints

Old age is like a minefield: if you see footprints leading to the other side, step in them.

1

—GEORGE VAILLANT

If the task of young adults is to create biological heirs, the task of old age is to create social heirs.

2

—GEORGE VAILLANT

Speaking at the Raises not Roses festival in 1979.

O

THER THAN DISEASE, THE PARAMOUNT DANGERS OF ACT III are loneliness, depression, and lack of purpose. These are, to a large degree, matters that have to do with the personal choices we make at this stage of our lives, what we choose to do or not do. When we feel we have purpose in our lives, the loneliness and depression seem to fade more into the background.

Okay, so my back aches, but I’m passionate about what I’m doing. Sure, I lost my network of friends at the office when I retired, but I’m going out and making new ones.

Just as the Third Act is the time for journeying inward to allow the flowering of consciousness and growth, it is also the time to radiate that consciousness outward as a resource not only for our own self-fulfillment but for the world, as well.

Think of the bright blooms that burst forth from invisible, underground rhizomes to catch the sun. This new spring growth carries the sunshine—transmuted to sugar, thanks to chlorophyll—back to nourish the root. In us humans, the process is also circular: The outward manifestation of our inner growth is what loops back and ensures that our inner self is nourished.

But it is the outer–what we

do

—that becomes our personal footprint, our ultimate identity. We are what we do.

Life can be taken away without death. We can let depression, self-pity, resentment, and grumpiness fossilize us so we’re not of much use to anyone. But why shortchange ourselves, now of all times? Is that what we want our legacy to be? Why not deliberately start to live so that the breakdown of the youthful self can lead to the breakthrough of an emerging elder self?

3

The Jungian analyst Helen Luke wrote, “To our wonder, we may find that now it is time to become aware of our oneness with everything and everyone other. Instead of ‘I am not this, I am not that person or thing or image,’ we begin to affirm, ‘I am both this and that’ and to glimpse the meaning of ‘I am’ as the name of God.”

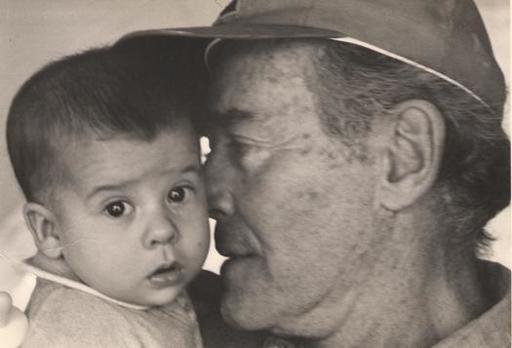

I took this picture of Dad holding baby Malcolm.

We can consciously cultivate these inner qualities in ourselves—trustworthiness, less ego, acceptance of differences. This is how we assume the role of sages, shamans, wise women who radiate a vision that beckons those who are younger more fearlessly into their own Third Acts. The very young may no longer need us to forage for food, an evolutionary imperative for grandmothers in hunter-gatherer times, but they need us to teach and inspire them. It is understandable for us, especially those of us at the far end of Act III, to feel a special affinity for children. Unlike those in midlife, the very young share with the old a proximity to what Joan Erikson called “the shadow of non-being,” the thin membrane that separates life and nonexistence, which is forgotten in the glare of midlife.

There’s a lofty word for this nurturing of the younger generations, or of individuals of any age: “Generativity.” It’s something the experts all agree is a central component of successful aging. The psychiatrist Erik Erikson coined the term to describe moving from a focus on oneself to a focus on a broader social radius, giving to the community and to the larger world. It involves the ability to care for and guide the next generation, to give of oneself to those coming up, by mentoring, coaching, guiding, nurturing them. The young have inherited certain traits genetically; we can pass on other traits to them through teaching and example.

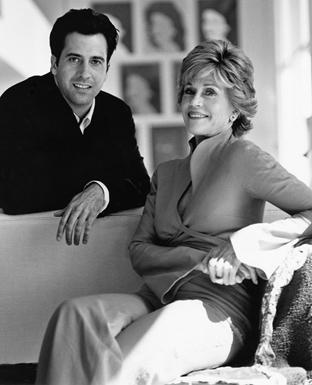

With my son, Troy, in 2007.

KURT MARKUS

My granddaughter Viva, around four years old.

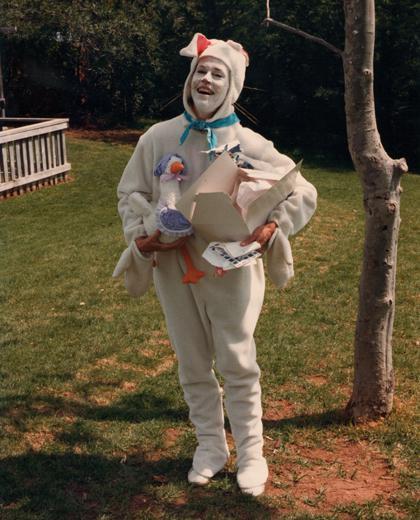

Me as the Easter bunny in 1976.

Me as the Easter bunny in 2011, with my granddaughter Viva (second from right).

Generativity also means being concerned with the future of the planet. You can think of it as revolutionary. If Generativity were more widely embedded in our social fabric, with all the caring and compassion for young people that it signifies, everything would be different.