Prisoner of Fate (43 page)

Authors: Tony Shillitoe

A BRIEF HISTORY OF WESTERN SHESS

The title of Shess for the vast western regions first appeared on cartographers’ documents during the seven-century reign of the Ashuak Empire, when Emperor Haarva began his expansionist crusade, and the Ashuak word ‘Shess’, meaning ‘foreign ones’, referred to a conglomerate of tribal factions with diverse cultures and languages. Despite disharmony and constant factional fighting between the many tribes, the great Ashuak armies failed to control the land they invaded. Instead, they learned that a disunited enemy was more troublesome than a united one because they were constantly harassed and confronted by new tribal groups who did not accept that the defeat of their neighbours also signified Ashuak rule over them. During the period of the Ashuak Empire, individuals sometimes tried to unite tribal groups against the common enemy. The concept of nationalism never superseded parochial tribalism, but the Ashuak principles of expansion and imperial rule took root, and after the Empire collapsed the strongest tribes in the north and west gradually dominated their neighbours to establish fledgling kingdoms.

Western Shess first took shape under the warrior chieftain Bigaxe Royal, a veteran of several battles with the Ashuak invaders. Bigaxe declared himself king of his region, demanding that his neighbouring tribal leaders recognise his sovereignty, and ruthlessly enforced his leadership over the many dissenters. Curiously, Bigaxe retained the Ashuak name for the region, probably because the only existent maps of the land were Ashuak in origin.

Royal successors settled their capital at Port of Joy and extended dominion further north and east during three centuries of Royal control, but rival kingdoms in the north in mountainous countryside eventually halted expansion. To the south, fierce tribal resistance, reminiscent of the war against the Ashuak invaders, stopped the kingdom from growing larger.

Although a patriarchal lineage, the death of King Godson Royal from illness shortly after the death of both his sons in battle left his only remaining child, his daughter Sunset, to succeed to the throne. Queen Sunset Royal defied numerous political manoeuvres to prevent her succession and assassination attempts once in power to successfully rule for twenty-seven years, before her son, Future Royal, began to fight for the throne, backed by religious rebels.

Religion is split between the ancient shamanistic forms with a multiplicity of spirits informing their followers, and the spreading monotheistic Jarudhaism imported from the eastern lands.

Jarudhaism is a corruption of the faiths originally started in the old eastern empires and kingdoms, a blend of Hohdaism and Jaru, along with some of the teachings of the philosopher Alwyn, called Alun in the

Shessian sect, as well as aspects of the shamanistic beliefs of the earlier Shess tribes. In its simplistic form, Jarudha is the one god who created the world and all of the people, and who has set down his laws for life through a series of great books collectively called

The Word. The Word

’s origins can be traced back to the Hohdan priests of the Ashuak Empire and a text called

Jaru’s Gift

that arose from earlier works written by Jaru philosophers, but subsequently

The Word

has been expanded to encompass at least fifteen known philosophical and religious works. Followers of Jarudha believe that Jarudha’s hand guides the affairs of the world, and that Jarudhan disciples only act according to His Will. They also believe that the world is corrupt and sinful, and that the time is approaching when Jarudha’s disciples will rise and assert dominion over the unfaithful who will be converted or destroyed.

In Western Shess, Jarudha’s disciples are synonymous with magical ability that is called the Blessing. Acolytes who demonstrate genuine magical skill are elevated to the rank of Seer, and the Seers believe that they are the vehicles for moral and spiritual consistency and reform. Jarudhaism is confined to the capital city, Port of Joy, and nearby towns. Outlying villages do not have Jarudhan representatives living in them.

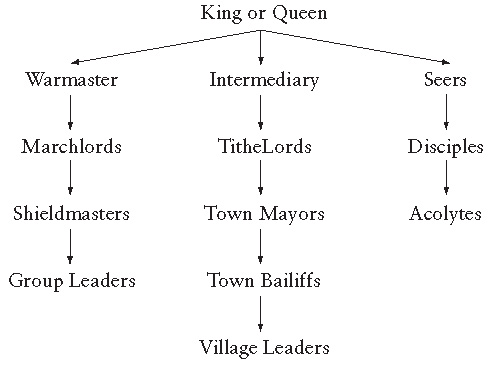

The political structures are quite simplistic because of the tribal roots and brutal determination of Bigaxe Royal and his successors to keep control. Essentially the regent is the supreme authority and law, and the leadership beneath is militaristic. The religious leadership is the only exception, and tensions between the Royals and the Jarudhan disciples have been taut throughout the kingdom’s history.

The Royal influence as a physical presence seldom extends beyond ten days’ travel from Port of Joy, so many of the outlying farming districts and villages are not directly affected by the laws and edicts enforced in the city and close towns. Many of the distant villages are operated communally or in loose democratic ways, and taxes are paid, sometimes irregularly, as tithes to representatives of the local Tithe Lord.

The naming tradition has always centred on people being identified with their employment or place where they were born. Before the rise and fall of the Ashuak Empire, Shessian inhabitants had single names, but the Ashuak use of surnames was adopted and retained after the Empire collapsed. A woodcutter or butcher would be called Woodcutter or Butcher as the surname and then words commonly used in the trade were often used as first names. Hence there might be a family of three boys named Log, Crossgrain and Handsaw Woodcutter.

Children born into the Butcher family might be named according to cuts of meat or implements or even animals.

Surnames do not automatically identify related families. Farmer is a common surname, for example, and there would be unrelated Farmers in the same village and across the entire kingdom. Of course, descendants of a family of Sailors can move into other working industries, in which case someone named Hawser Sailor could well be the bartender in a local tavern, while Seam Clothmaker could be a farmer. Sometimes people also change their surnames when they change work. So Labourer Pullman, whose father was working on the wharves, could join the army and change his name to Labourer Onespear by choice. Western Shess has not yet conducted an official census or established a corporate identification system and so personal names are only useful for personal identity. Foreign names are evident in the cities and large towns, but the rural communities generally retain the traditional and simple name forms.

Shessian language has specific grammatical rules. A sentence is organised with the verb, the subject and then the predicate. Common usage has reduced many sentences to phrases best understood in expression than in straight translation.

The English sentence, ‘I am eating my food’ becomes approximately ‘Eating I am my food’—‘Doshalinae emahdu mahdu shali’—although its more accurate expression would be ‘Doshalinae emahdu’ (‘I’m eating’). In common usage, however, it is expressed as ‘Doshemah’.

Thus, ‘If you touch my wife, I will kill you’ becomes ‘Kill you I will, if touch my wife you do’—‘Sunahso yahwu emah, ha kaso mahdoos yahwu.’

Greeting is simple. ‘I’m pleased to meet you’ in formal form is ‘Jahn yahwu emahdu tessa’, but it’s common usage is a brief ‘Jahntess’, which serves as ‘hello’ does in English. The equivalent to ‘good day’ is ‘Jarubahn’, which originated from a very complicated ‘Umen emahdu ehae yahwu nena fueppo bahn t’Jarudha’, meaning ‘I am happy to see that God has given to you another day’.

‘I have planted the rain crop’ is expressed as ‘Nesoss emah epphanuhk’, and ‘Light the fire’ is ‘Ooh shah’, often expressed as a single word. The common soldier’s insult ‘Your mother fucks everyone!’ is ‘Hur yahwudo oyehn epyahn!’ although it’s generally expressed as ‘Hur epyahn!’

The language has developed some pleasantries, so that the English ‘please’ is expressed as ‘tessa’ at the completion of a sentence, as in ‘May I please speak to you?’ - ‘Casan emah yahwu, tessa?’, and ‘Excuse me’, becomes ‘Mahni mah’. But Shessian is an abrupt, focussed language in the main, and niceties are generally reserved for the royal courts.

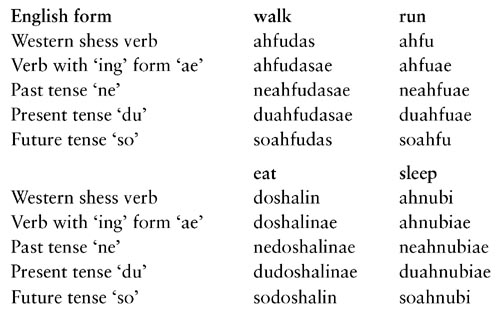

Verbs are simplistically broken down into identified action, past (ne), present (du) and future (so) forms. For example:

English

/Shessian

afternoon

fulanbahn

air

hor

am

du

and

ut

another

fueppo

are

hi

army

eppodofahmah

big

jasu

by

t

chair

doahpin

crop

epphanuhk

cycle

ejas

day

bahn

death

doyanah

die

yanah

dying

doyanahae

early l

an

earth

dun

eat

doshalin

eight

bada

eighty-eight

mekbadabada

eleven

tata

evening

lanfubahn

excuse (verb)

mahni

farm

shukoh

father

doshoh

fifty-seven

mekdenja

fire

shah

first

tay

five

den

food

shahlin

four ay

fuck

hur

give

na

grain/seed

nuhk

happy

umen

home

dohahni

house

hahni

husband

doos

I

emah

if

ha

jump

naep

kill

sunah

late

fulan

less

enno

light

ooh

little

fujasu

man

dosh

many

ep

me

mah

meet

jahn

men

epdosh

midday

midbahn

middle/between

mid

midnight

midfubahn

mine/my

mahdo

moon

fubahnooh

more

eppo

morning

fujasubahn

mother

oyehn

night

fubahn

nine

lun

no/not

fu

one

ta

own/belong

do

plant

soss

please

tessa

rain

szash

rebel

nahsten

rebellion

dunahsten

run

ahfu

see/look

eh

seven

ja

sit

ahpin

six

net

sleep

ahnubi

soldier

dofahmah

speak/talk

casan

sun

horshah

ten

mek

thirty

mekest

thirty-three

mekestest

three

est

touch ka

twelve

ota

twenty

mekot

two

ot

unhappy/sad

fu-umen

walk

ahfudhas

war

fahmah

water

ar

wife

mahdoos

wine

chen

women

epyehn

woman

yehn

yes

hah

you

yahwu

your

yahwudo

- Army: usually a grouping of one hundred thousand soldiers, led by a Warmaster.

- March: a grouping of twenty thousand soldiers, led by a Marchlord; an army consists of five Marches.

- Shield: a grouping of one thousand soldiers, led by a Shieldmaster; a March consists of twenty Shields.

- Group: a grouping of fifty soldiers under the command of a Leader; a Shield consists of twenty Groups.

- Party: a grouping of ten soldiers; a Group contains five Parties.

Length measurement is a direct derivative of the human body. The smallest measuring unit is called a ‘width’, which is the original equivalent of an average person’s thumb width, although there is a standardised rule. Ten ‘widths’ makes a ‘hand’ length, and five ‘hands’ is the equivalent to an arm ‘length’. Thus for measuring purposes Shessian people talk of ‘widths’, ‘hands’ and ‘lengths’. They also link length measurements to travel distance measurements through ‘paces’ - the length of an average man’s stride when walking - with a ‘pace’ and a ‘length’ being accepted as an interchangeable measurement.