Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power (13 page)

Read Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power Online

Authors: Steve Coll

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #bought-and-paid-for, #United States, #Political Aspects, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Business, #Industries, #Energy, #Government & Business, #Petroleum Industry and Trade, #Corporate Power - United States, #Infrastructure, #Corporate Power, #Big Business - United States, #Petroleum Industry and Trade - Political Aspects - United States, #Exxon Mobil Corporation, #Exxon Corporation, #Big Business

This, increasingly, was the underlying structure of Washington policy debates: a kaleidoscope of overlapping and competing influence campaigns, some open, some conducted by front organizations, and some entirely clandestine. Strategists created layers of disguise, subtlety, and subterfuge—corporate-funded “grassroots” programs and purpose-built think tanks, as fingerprint-free as possible. In such an opaque and untrustworthy atmosphere, the ultimate advantage lay with any lobbyist whose goal was to manufacture confusion and perpetual controversy. On climate, this happened to be the oil industry’s position.

Raymond’s public affairs chief, Kenneth P. Cohen, directed a network of allies and grantees in Washington who created havoc in the climate science debate. Walt Buchholtz, like Cohen a veteran of Exxon’s Chemical Company, served as a policy adviser to The Heartland Institute, a Chicago-based free-market group that frequently published tracts challenging the scientific basis for global warming fears. The Competitive Enterprise Institute, on L Street, received hundreds of thousands of dollars from Cohen’s department; its free-market advocates filed lawsuits challenging the implementation of climate reviews by the Clinton administration, on the grounds that the scientific data relied upon was unreliable. Exxon provided $373,500 in 1998 and 1999 to the Annapolis Center for Science-Based Public Policy, a nonprofit that backed some of the most prominent scientists skeptical of mainstream science on climate; the center would eventually honor Oklahoma senator James Inhofe, the Congress’s most ardent doubter of global warming, for his work in promoting “science-based public policy.”

20

The individuals writing and lobbying in the network Exxon funded described themselves as honest, libertarian skeptics who had the courage to challenge conventional scientific wisdom. They did not feel polluted by the receipt of Exxon money any more than liberal-minded campaigners might feel polluted by the receipt of grant funding from, say, the George Soros–backed, left-leaning philanthropy, the Open Society Institute. Relatively few of the thinkers in the network aligned with Exxon’s views were climate scientists, however. They typically concentrated on economics and public policy matters. The books authored by members of this movement included titles such as

Red Hot Lies: How Global Warming Alarmists Use Threats, Fraud, and Deception to Keep You Misinformed

and

The Global-Warming Deception: How a Secret Elite Plans to Bankrupt America and Steal Your Freedom.

Inside ExxonMobil’s K Street office, the sense among some of the lobbying staff was that a lot of this provocative activity was being stoked by the public affairs department in Irving with the idea that it would please the boss, Raymond, whose views on climate policy were well known; a few worried that the fringe campaigners might ultimately endanger shareholders by creating litigation or regulatory risk for the corporation.

The A.P.I. internal documents rooted out by investigators for environmental groups did not contain the kind of smoking-gun evidence about climate science that was earlier unearthed from the tobacco companies. The tobacco industry’s documents made clear that corporate scientists knew that smoking was harmful, but nonetheless buried the facts and published misleading studies. In the case of the emerging controversies over climate, there was no evidence that A.P.I. or Exxon maliciously distorted in-house scientific research. The corporation’s advocacy campaigners were now inching toward dangerous legal territory, but in the main, the “Action Plan” documented a subtle strategy involving the use of money to advance corporate interests by exploiting the uncertainties and argumentation that can be innate to science.

O

n May 31, 2000, in Dallas, six months after the Mobil merger, Lee Raymond stood before the first annual meeting of ExxonMobil shareholders—an unruly gathering of religious leaders, environmentalists, and other dissidents who regularly used the meeting, which was required by law, to pressure Raymond over his corporation’s public policies, particularly on the environment, alternative energy, and climate. One such activist had just accused Raymond of ridiculing those in the audience who disagreed with him.

“I’m not ridiculing anybody,” Raymond answered. “And I resent the assertion that I am. We have a difference of view. This is a democracy. . . . And frankly, I’m not interested in being ridiculed. . . .”

Another speaker demanded “a long-term solution to global warming”; applause erupted.

Raymond possessed no impulse to restrain himself on this subject. “If the data were compelling, I would change my view,” he once said. “Ninety percent of the people thought the world was flat. No?”

Now, Raymond went further than he had ever gone in locating his corporation’s place in the global warming debate.

“Mark, would you provide me a slide on the seventeen thousand scientists?” Raymond asked an aide.

A slide duly flashed on a wide screen. It depicted a petition organized by anti-Kyoto campaigners and signed by thousands of scientists. The idea was to demonstrate that many respectable scientists doubted key aspects of the I.P.C.C. consensus about the likelihood of human contributions to global warming. The petition’s credibility had already been undermined by testimony presented to Congress demonstrating that its signatures included those of pop musicians such as the Spice Girls and James Brown. If Raymond knew about these problems, he did not care.

“This is a petition signed by seventeen thousand scientists. . . . ‘There is no convincing scientific evidence that any release of carbon dioxide, methane, or other greenhouse gases is causing or will in the foreseeable future cause catastrophic heating of the earth’s atmosphere and disruption of the earth’s climate.’ So, contrary to the assertion that has just been made that everybody agrees, it looks like at least seventeen thousand scientists don’t agree. My point is not that these seventeen thousand are right and you’re wrong. Your point is you’re right and I’m wrong. I’m not saying you’re wrong. What I am saying is there is a substantial difference of view in the scientific community as to what exactly is going on. . . . We’re not going to follow what is politically correct. . . .”

He went on. “Mark, would you first give me the three-thousand-year slide?”

Another image flashed on the screen. It showed lines undulating on a graph.

“That’s the earth’s temperature as best these scientists are able to estimate what it was for the past three thousand years,” Raymond continued. “It’s been a long time since I went to graduate school. But if you just eyeball that, you could make a case statistically that, in fact, the temperature is going down.

“I’m not asserting that. Similarly, I reject the assertion that it’s going up.”

21

T

he 2000 presidential campaign was a dead heat to the finish. Al Gore, concerned about winning coal states, muted his views about the dangers of global warming. The handful of quotations and policy statements George W. Bush offered on climate were rife with contradictions. Asked about global warming during a debate with Gore, he said that “it’s an issue that needs to be taken very seriously,” but he also suggested that some climate scientists were “changing their opinion a little bit,” without explaining himself further. Bush denounced the Kyoto Protocol as too harmful to industrialized countries like the United States, but his campaign also issued a policy document urging mandatory reductions of four major pollutants, including carbon dioxide. Bush’s decision to name CO

2

as a pollutant suggested that he might accept Kyoto’s broad goals.

22

After his inauguration, in addition to Vice President Cheney’s energy policy task force, the president named a less-publicized cabinet-level working group to review climate change science and policy. The members included Secretary of State Colin Powell, Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill, Commerce Secretary Don Evans, Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham, and Christine Todd Whitman, head of the Environmental Protection Agency. Cheney also took part. John Bridgeland, director of the White House’s Domestic Policy Council, and Gary Edson, a deputy national security adviser, organized the work. They recruited a half dozen career climate scientists working in federal departments to move temporarily to the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, next to the White House. There they organized climate science and policy briefings for the new cabinet members.

“It was a heady time,” recalled one of the participating scientists, Aristides Patrinos. “The potential was so great.” He and other career scientists summoned to the White House had concluded, on the basis of the evidence from the campaign and the transition, that Bush shared their sense of urgency about the need to control greenhouse gases. Because the president was a Republican with a background in the oil industry, Patrinos thought, “This was like when [Richard] Nixon went to China—Bush could really be the one who would do something with respect to climate change.”

23

Patrinos and his colleagues delivered science lectures to the cabinet group at rotating sites—one time at State, the next at Agriculture, and so on. James Hansen of N.A.S.A. delivered one private lecture; James Edmonds of the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory gave another concerning the mix of policies and technologies that might be required to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations. During these sessions, which were unpublicized and closed to all but senior staff, Patrinos was impressed at how open-minded some of the cabinet members, such as Colin Powell and Don Evans, seemed to be. As the lectures went on, however, he also became concerned about the demeanor of Vice President Cheney.

The scientists laid out vivid, illustrated accounts of the damage global warming could bring in the future: melting glaciers, rising sea levels, droughts, and severe storms. They offered specific forecasts about the impact global warming could have on public health and on the economy. One of the lecturing government scientists described the possibility of rising sea levels in “lowland areas in Miami, south Florida,” as Patrinos recalled it.

Hearing this, Cheney shifted uncomfortably, Patrinos remembered. He looked like a “raging bull. . . . He got up, paced back and forth, then stood next to me, and I could sense that he was not a happy camper.” Cheney remained silent.

24

The vice president soon preempted the climate task force’s work. Haley Barbour, a former chairman of the Republican National Committee who had become a lobbyist for a utility firm that stood to lose if greenhouse gases were regulated, urged Cheney in a March 1 memo to persuade Bush not to align with the “eco-extremism” of those who saw carbon dioxide as a pollutant. Two weeks after Barbour’s memo landed, Cheney arranged for Bush to sign a letter to Congress repudiating his campaign position about CO

2

—without so much as informing Christine Whitman, the new Environmental Protection Agency (E.P.A.) chief, in advance.

Whitman called Treasury Secretary O’Neill. “Energy production is all that matters,” she said. “[Cheney] couldn’t have been clearer.”

“We just gave away the environment,” O’Neill replied.

25

A

few weeks later, ExxonMobil’s climate policy specialist Randy Randol sought a meeting with Under Secretary of State Paula Dobriansky, the administration’s lead diplomat on global warming issues. One of Dobriansky’s senior aides, career foreign service officer Ken Brill, prepared a briefing memo. It noted: “Mr. Randol has asked for this meeting at the suggestion of our Ambassador-designate to Sweden, Charles Heimbold, who served on the board of ExxonMobil.” Heimbold, the former chief executive of the drug maker Bristol-Myers Squibb, felt that “we should hear from Exxon/Mobil scientists who have perspectives on the climate change debate that are not consistent with the science that has supported our climate policy until now.” Brill suggested some talking points for the under secretary that might assuage the corporation’s lobbyist:

Understand Exxon/Mobil’s position that there should be no precipitous policy decisions if scientific uncertainties remain. . . . Administration will continue to oppose the Protocol, but must move forward on improving our scientific understanding. . . . We will, however, continue to rely on input from industry and other friends as to what constitutes a realistic market-based approach.

26

Four

“Do You Really Want Us as an Enemy?”

E

arly in March 2001, an Acehnese rebel commander known as Abu Jack (“Father of Jack,” in Arabic) telephoned Ron Wilson, a Texas A&M graduate who ran ExxonMobil’s operations in Indonesia. The time had arrived, the caller said, for the corporation to make payments to his separatist guerrilla force. Other oil and gas companies paid for the right to operate in the disputed province of Aceh, Abu Jack claimed. “So must ExxonMobil” was the essence of his message.

Wilson told Abu Jack—whose given name was Zackaria Ahmad—that he would take the demand to his supervisors. He hung up and soon called the United States embassy. He and other ExxonMobil officials disclosed that they had evidence that rebels were stockpiling heavy weapons near their facilities. They also declared they would never pay extortion money. “We are very close to closing down,” they reported.

1

When Lee Raymond acquired Mobil Oil, he also acquired a small war. It was a conflict that Mobil had been struggling with for decades. In any merger, the acquiring party often finds that the target company has a few problems that are worse than expected. Mobil’s role as a party in one of fractious Indonesia’s most violent separatist insurgencies quickly emerged as such a case. The war was emblematic of ExxonMobil’s dilemmas in the era of resource nationalism. The corporation’s options to acquire “equity” oil and gas outside of the United States, Europe, and Australia were increasingly limited to poor and weak states prone to internal violence. And in a period of Internet-enabled corporate responsibility campaigns, oil drilling in such countries seemed to attract guerrillas and human rights researchers in equal measure. Exxon had largely avoided the problems that arose from extracting oil and gas in the midst of small wars. The acquisition of Mobil’s far-flung properties—in Indonesia and West Africa, especially—would force Raymond and his management team to come to terms with issues they had little experience managing, including the conduct of security forces guarding ExxonMobil oil and gas fields and the geopolitics and diplomacy required to bring oil-related insurgencies to a negotiated end. Raymond’s one-size-fits-all Operations Integrity Management System was not especially well suited for the murky violence, corruption, and shifting politics Exxon now confronted in Indonesia.

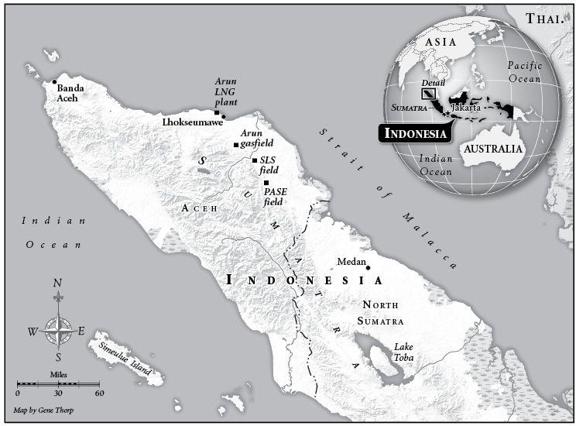

Mobil had been present in the country for decades. During the 1970s, it had acquired access to a lucrative natural gas field on the northern tip of Sumatra, in the province of Aceh (pronounced

Aah-chay

)

.

The latest round of separatist conflict had been under way for almost twenty-five years in a poor but lush seaside region of rain forests, mountains, rice paddies, and palm oil plantations. Aceh had been an independent Muslim kingdom ruled by sultans for more than four centuries. A Dutch colonial army landed in 1873; the invading commander died within a week and so did many of his men. The first Acehnese resistance war lasted forty years. It calmed and then resumed after Indonesia gained independence from the Netherlands in 1949. From the 1970s, Aceh’s struggle to control its own affairs revolved considerably around natural gas and the question of who should benefit from its sale. The gas lay buried in the Arun field, as it was known, beneath an expanse of fertile, palm-laden land along the northern mouth of the Strait of Malacca, near the town of Lhokseumawe.

A large share of the Arun field belonged to Mobil. It contained about 17 trillion cubic feet of gas (the equivalent of just under 3 billion barrels of oil) and proved to be highly remunerative: In the decade leading to the Exxon merger, the Arun field accounted for about a fifth of Mobil’s overseas revenue from oil and gas production. The subsidiary that extracted Aceh’s gas and then liquefied it for transportation to Japan and other markets earned $295 million in profits in 1998, $311 million the next year, and $498 million the year after that. The earnings reflected lucrative contracts Mobil had negotiated during the panicked period of the Arab oil embargoes and the early Iranian Revolution, when many energy-importing nations in Asia feared they would not have access to supply at any cost and proved willing to pay relatively high prices for guaranteed long-term deliveries.

“My nightmare is to pick up the

New York Times

and read that both Nigeria and Indonesia are in flames,” Lou Noto, Mobil’s chairman, told industry colleagues in the late 1990s. Those two countries accounted for a lopsided share of Mobil’s profits; both were wracked by internal rebellions. Noto, therefore, had extra incentive to muddle through the Aceh war. ExxonMobil, under Lee Raymond, was not going to lightly set aside half a billion dollars in annual profit, either, but the merged corporation had more financial flexibility to tell the likes of Abu Jack to go away. The Indonesian government’s position was more like Mobil’s had been—it was dependent on keeping the gas profits flowing. Its take from Aceh was about $1.2 billion in 2000, more than a fifth of the government’s total oil and gas receipts that year, and about 6 percent of its revenues from all sources, before international aid.

2

To a great extent Aceh’s war had evolved into a contest over who could bargain or shoot his way to control the Arun field’s cash flow. One of the contenders was a former New Yorker named Hasan di Tiro, a charismatic Acehnese nationalist leader to some, and to others, “a quixotic, self-promoting political dabbler prone to hysterics and exaggeration,” as one biographer put it. Di Tiro was a great-grandson of a heroic nineteenth-century anti-Dutch guerrilla fighter. He grew up in unassuming circumstances in Aceh, migrated to Indonesia’s main island of Java to attend law school, and then won a scholarship to the United States in 1950, at the age of twenty-five. He attended Columbia University and later worked in the information department of the Indonesian mission to the United Nations. He made the acquaintance of Edward Lansdale, the Central Intelligence Agency’s legendary Asia hand during the cold war. Di Tiro found himself “circulating in the eddies and backwaters of international diplomacy” in New York.

3

He absorbed the radical ideas of Marxist-influenced, postcolonial liberation movements that spread worldwide during the 1960s, but he also tried to provide for his family through business ventures back in Indonesia. In 1974, one of Di Tiro’s companies, Doral Inc., bid for a contract to build a pipeline connected to Mobil’s Acehnese gas field; the job went instead to the San Francisco–based Bechtel Corporation. Di Tiro’s opponents later emphasized this commercial setback as a cause of his final radicalization. Di Tiro told a different story: Soon after he lost the pipeline bid, he was flying aboard a private jet when its engines died. He promised himself that if he survived, he would lead a revolution for Acehnese independence. He had reached late middle age and believed that he had “lived long enough,” he told an interviewer. His biographer felt that Di Tiro was describing a “midlife crisis of sorts.”

4

He founded the Gerakan Aceh Merdeka, or “Free Aceh Movement,” known as G.A.M. His followers snuck into the province from Malaysia and opened their “armed struggle” in the rain forests and volcanic hills of the rugged Pidie region on October 30, 1976. Di Tiro issued a declaration of independence six weeks later, drawing on his American education: “We, the people of Aceh . . .” he began. His war strategy, he later wrote, was to shut down “foreign oil companies . . . to prevent them from further stealing our oil and gas.” G.A.M. leaflets warned Mobil and Bechtel employees to “pack and leave this country immediately.” Di Tiro organized about three hundred fighters and managed to make contact with Muammar Gaddafi, the Libyan dictator; he sought training for his men at Libyan camps. “They have Mobil Oil,” Di Tiro reportedly told Gaddafi, “so you must support us.”

5

Because Mobil employed nearly three thousand Acehnese directly or by contract, it proved risky for G.A.M. to target the company; job losses would alienate the rebels’ population base. Abu Jack’s extortion demand reflected the murky war that had evolved in reaction to these constraints: Rather than throw Mobil out, G.A.M. sought to access the corporation’s revenues, directly and indirectly. Racketeering had become commonplace on both sides of the conflict.

The violence was sporadic, but it was often most intense around the sprawling, fenced-in Mobil gas facilities. On the north side of Lhokseumawe (the town’s name meant “Everything Deep,” a reference to the swampy terrain in which it sat) stood the factory-size Arun liquefied natural gas (L.N.G.) plant. On the other side of town lay the gas fields themselves, spread out across tens of square miles, intermingled with inhabited villages. A modern gas well is relatively unobtrusive in comparison to an oil well: a chest-high, cylindrical metal structure with no moving parts. Mobil installed these robot-looking creatures in fenced areas with names such as Cluster I and Cluster II.

Point A was the main administrative and engineering headquarters for the gas fields. ExxonMobil compounds worldwide displayed a universal design: yellow security lights, high double fences at the entrance, and just inside (after the post-

Valdez

safety campaigns evolved) a large billboard declaring “Nobody Gets Hurt.” About 220 expatriate employees—Americans, Australians, Japanese—lived within ExxonMobil’s compounds in Aceh. Around them lay clayroads, rice paddies, grazing fields with a few stray cattle, and tin-roofed village homes.

G.A.M. fielded a few thousand guerrillas; its most sophisticated weapons were semiautomatic rifles and rocket-propelled grenade launchers. The guerrillas taxed and extorted villagers and erected roadblocks to take money and property from passing vehicles. A few miles away from a G.A.M. roadblock constructed from fallen tree trunks, Indonesian soldiers might man their own barrier, peering into cars in search of suspicious-looking young Acehnese men.

Mobil had adapted to the war without ever missing a gas delivery. Early in 2001, however, a stream of extortion letters and phone calls started to arrive at ExxonMobil’s offices. The corporation’s security department, which ran its own intelligence operations in the province, heard “widely divergent rumors,” as a U.S. embassy cable put it, about what lay behind the letters and whether the commander known as Abu Jack was, in fact, responsible: “One source says he’s now in jail and that imposters are making the threats; others say he is a double agent in the employ of the security forces.”

6

ExxonMobil’s security department had also received reports that Indonesian executives at a partner company had recently paid a $100,000 ransom to win the release of a kidnapped Indonesian-born executive. The alleged payoff had “heightened concern” that rebels might now be encouraged to kidnap someone at ExxonMobil, perhaps an expatriate. To deter G.A.M., ExxonMobil suggested to the U.S. embassy in Jakarta that the corporation take out newspaper advertisements declaring its “refusal to make illicit payments”; the embassy judged, however, that “any effort to publicly defy the G.A.M. . . . is not advisable.”

7

Abu Jack, or whoever he was, telephoned ExxonMobil once more on the morning of March 9. A large rebel force had gathered to attack the corporation’s gas fields, the caller reported; G.A.M. had ordered villagers in the area to leave. ExxonMobil’s local employees could see that nearby residents were, in fact, leaving. Around the same time, a mortar attack and a roadside pipe-bombing targeted a bus carrying corporate personnel. The evidence suggested to ExxonMobil that G.A.M.—or some faction of the undisciplined rebel movement—had changed its targeting policy to go after the company directly, either to advance its extortion campaign or because senior G.A.M. leaders had quietly decided that ExxonMobil was now an enemy of its rebellion, in a way it had not been seen as before.

8

Ron Wilson, who was the president of Mobil Oil Indonesia, the subsidiary that managed all of ExxonMobil’s oil and gas operations in the country, decided he could wait no longer. He was accustomed to managing risk on behalf of expatriate and local employees, but he concluded that G.A.M. had now crossed a line. Wilson reported through ExxonMobil’s chain of command ultimately to Harry Longwell, Raymond’s executive vice president for upstream operations on the Management Committee, the corporation’s supreme governing council. Raymond’s judgment about the war he had inherited in Aceh, he recalled, was that “Mobil wasn’t shooting anybody, but obviously the military was going to protect” the gas field, “driven by orders from Jakarta, and Mobil was kind of in the middle of it.” Raymond entrusted the day-to-day decision making to Longwell.