Private Life in Britain's Stately Homes (32 page)

Read Private Life in Britain's Stately Homes Online

Authors: Michael Paterson

No other people brought the art of gracious rural living to such a pitch as the British. The combination of house, gardens, sporting events and social ritual created a way of life that was envied, and emulated, throughout the world – and which was deliberately transplanted by the British themselves throughout their empire. Afternoon tea, taken informally on the lawn, was the epitome of this world.

Hunting demanded skill and daring, and had been the archetypal sport of the country gentleman for centuries. Here a hunt meets at the local ‘big house’ in 1872. They could have stepped straight from the pages of a novel by R.S. Surtees, a satirist who brilliantly lampooned the ways of the Victorian hunting set.

Every country house had a stable-block, built around a yard and often architecturally imposing. The clock was to keep servants punctual. The horses’ stalls and the carriages were on the ground floor. Above lived the coachmen, grooms and stable-boys who looked after them. They, and their families, formed a small community distinct from other domestic staff.

The coachman, an experienced professional, was an important member of any country house staff, yet he spent much of his time on trivial errands – fetching guests from the railway station, taking his mistress shopping or on local visits, and perhaps merely driving his employer’s children round the park to give them fresh air.

Girls typically entered service in their early teens but before starting had to buy their own uniforms, and it took about two years to save the necessary sum. Maids were almost always photographed in the black dresses (their best garments) which they wore in the afternoons to serve.

In the mornings, they looked rather different. They wore print dresses for cleaning the house, a series of chores that occupied the first half of the day. Servants were very seldom allowed access to the gardens, and their rooms were often positioned so they could not even see them. This picture was probably taken while their employers were away for the Season and greater freedom was possible.

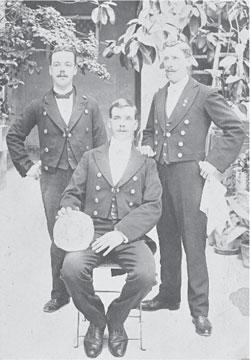

Male servants fared better. They earned more, and did not have to buy their clothing. Footmen had liveries suitable for everyday wear in the house …

… for accompanying their mistress on calls …

… and for serving at grand dinners. These uniforms were naturally expensive to make, and were handed down through generations of servants. The men had to fit the coats rather than the other way round. The result could be intense discomfort.

As well as a staff of indoor servants, there were numerous men and women who seldom set foot in the house: gardeners, gamekeepers, grooms, laundresses and dairy-maids. Several of those seen here, photographed in about 1860, carry guns as a symbol of office. The women are probably not servants but wives. Outdoor staff lived in cottages on the estate and, unlike their indoor counterparts, were able to have families.