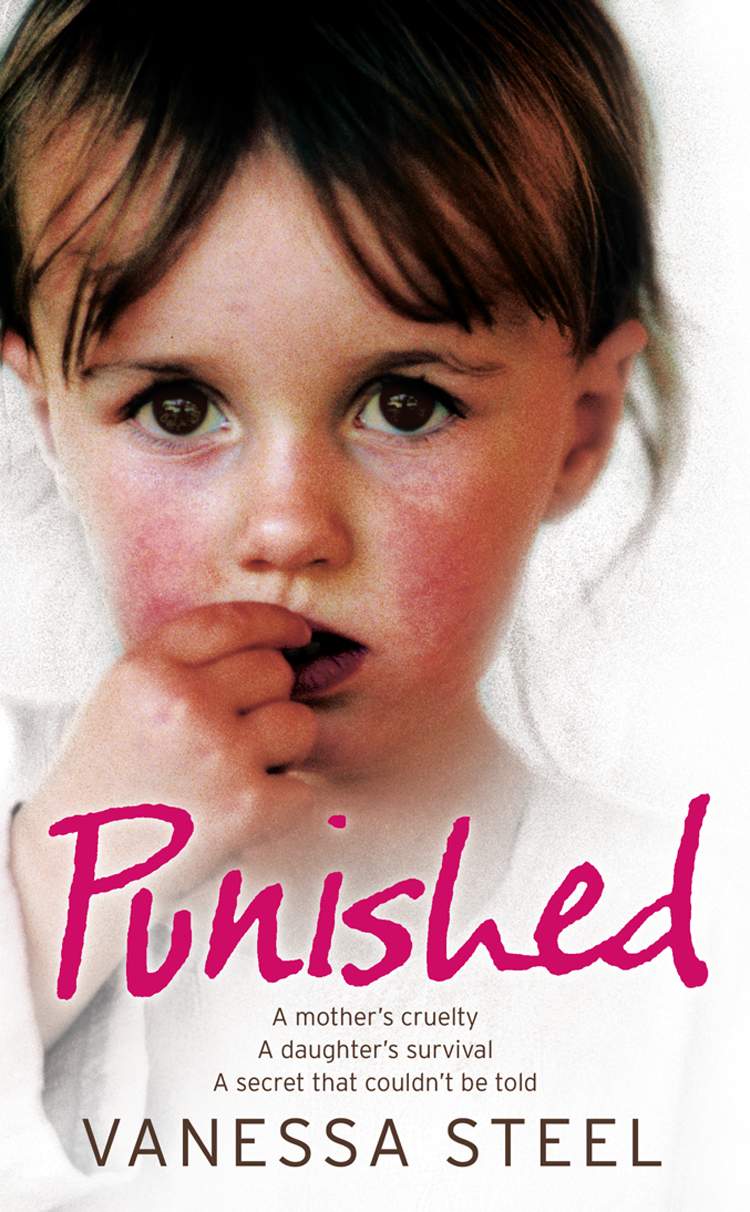

Punished: A mother’s cruelty. A daughter’s survival. A secret that couldn’t be told.

Read Punished: A mother’s cruelty. A daughter’s survival. A secret that couldn’t be told. Online

Authors: Vanessa Steel

A mother’s cruelty

A daughter’s survival

A secret that couldn’t be told

Vanessa Steel

with Gill Paul

This is a work of non-fiction. In order to protect privacy,

some names and places have been changed.

Title Page

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty One

Chapter Twenty Two

Chapter Twenty Three

Chapter Twenty Four

Chapter Twenty Five

Chapter Twenty Six

Chapter Twenty Seven

Chapter Twenty Eight

Chapter Twenty Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty One

Chapter Thirty Two

Chapter Thirty Three

Chapter Thirty Four

Chapter Thirty Five

Chapter Thirty Six

Chapter Thirty Seven

Chapter Thirty Eight

Chapter Thirty Nine

Epilogue

Exclusive sample chapter

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

I

turned my key in the lock of Mum’s door and pushed, but it wouldn’t open. Something was stuck behind it, blocking it. I pushed harder but couldn’t shift the obstruction.

What’s she done now? I wondered. Is she deliberately trying to keep me out?

Then I looked through the letterbox and saw a beige- stockinged leg – her leg.

‘Mum!’ I yelled. ‘Mum, are you all right?’

Stupid question. Of course she wasn’t all right. I shouted at the top of my voice – ‘Help me!’ – and the next-door neighbour hurried out to see what was going on.

Stuttering with shock, I called for an ambulance and told the operator we’d probably need the fire brigade as well to break the door down. While we waited for them I sat on the step calling to Mum through the crack of the door but getting no response. Was that her breathing I could hear? I wasn’t sure. My heart was racing like crazy and so many thoughts flooded my head I felt dizzy.

No, she can’t die. Please don’t let her die!

I couldn’t help feeling guilty that I hadn’t been there when she needed me, even though I had been dropping in every day to do her washing and cleaning.

‘Hold on in there, Mum,’ I whispered through the door. ‘You can make it, I know you can.’

Tears filled my eyes as I heard a distinct, low-pitched moan. She was alive.

* * *

One of the ambulance men managed to get his arm through the crack and shift her so that they could get in without breaking the door down. They gave her oxygen and she regained a groggy kind of consciousness. I stood, useless, a huge lump in my throat and sadness engulfing me.

It was at that moment I realized that it was finally time to let loose all the dark childhood memories I had suppressed for decades. The woman lying crumpled on the floor and fighting for every breath had made my childhood a living hell. Now I knew I was in no way ready for her death, because while she was still alive I might be able to force her to answer the questions that had plagued me throughout my adult life.

What had I done to make her hate me so much that she did so many cruel things to me? Did she remember all the times she almost killed me? Why did she allow me to be a victim of terrible abuse? Why didn’t Dad or any other family member protect me from her? Why did I still feel a responsibility towards her and long for her to show me some affection, despite all that she had put me through?

As my mother was lifted into the ambulance, I knew that I didn’t have much time left to find out.

What crime had I committed? Why had she punished me, endlessly and thoroughly and with spite and cruelty, from the day I was born?

M

uriel Pittam was never really cut out to be a housewife and mother.

She was the second of Charles and Elsie Pittam’s four daughters, and judging from the photographs in the family albums, she was much prettier than her sisters. From the way she looks at the camera, you can tell that she knows she is cute and is challenging you to acknowledge it. The Pittams were not rich – Grandpa Pittam was a watch and clock repairer – but it’s obvious from the pictures of little Muriel in her pretty dresses and ballet tutus that she didn’t want for anything.

By the time she was in her twenties, Muriel Pittam was an absolute stunner, and she knew it. The photographs in the family album show her as a glamorous young blonde. In one picture she is leaning against a gate in a two-piece suit with a tightly belted waist and high-heeled shoes that must have taken her well over the six-foot mark. In another, she’s wearing a smart floral dress with a fitted bodice and flared skirt. There’s even one of her posed on a rock like a mermaid, wearing a bikini. Bikinis were only invented in 1947, the year after the A-bomb was tested on

Bikini Atoll in the Pacific. Muriel must be wearing one of the first on the market.

All through my childhood, Mum often harked back to the glory days of her youth, when she worked as a seamstress and part-time model.

‘I used to make ball gowns, you know. Suits, day dresses, coats, wedding dresses, all of them hand sewn,’ she would say. ‘I worked for Isabel’s in Birmingham, where the fashionable ladies shopped. The wife of the head of Woolworths got her clothes there. And Arthur Askey’s wife. And I modelled. I had a perfect figure,’ she boasted. ‘Five foot eleven with a twenty-three-inch waist. My skin was flawless and photographers used to say I had the best profile they’d ever seen. There were photos of me modelling hats in the

Daily Mirror

.’

Young and gorgeous, Muriel Pittam had no problem attracting men. Over the years she often boasted to me about all the suitors she’d had and the marriage proposals she’d received and I’m sure it was all true. I saw at firsthand how she flirted with every man she came in contact with, from the plumber to her brothers-in-law. She obviously had the knack of twisting men round her little finger, with a shimmy of her slender hips and a coy smile. So when the youthful and less experienced Derrick Casey got within her sights – well, he didn’t stand a chance.

My father was engaged to a girl named Margery Wyatt when his elder sister Audrey brought home Muriel, her friend from the tennis club, for tea one day. The Caseys owned a very successful electro-plating business in Birmingham and Derrick already earned a good salary from it, so to Muriel’s eyes he must have seemed a

good catch. The Caseys’ imposing house stood in several acres of grounds and they had a gardener and housekeeper to help run it. Thomas Casey was well connected as a prominent member of the local Conservative party and a leading figure in the Anglican Church. By contrast, the Pittams lived in a semi-detached house in a working-class area and had very little social life outside its four walls. It was obvious that Derrick was Muriel’s way out of a life as a seamstress and into a respectable and comfortable upper-middle-class life, so using her intelligence, her wiles and her physical charms, she set out to win his heart.

A lot of other men Dad’s age were called up to fight in the Second World War, but Derrick hadn’t been because he had a shattered kneecap after a cricket ball injury which left him with a permanent limp and unable to straighten his left leg. He still loved to play sports – golf, cricket, snooker – and he was also a great reader, particularly fond of Shakespeare and poetry. He looks unbearably young in photos of that time – plump-cheeked, dark-eyed, hair not yet receding but already wearing his customary shirt and tie in every shot. He’s the kind of man any young girl would have been proud to take home to their parents: upstanding and respectable, with a nice face without being conventionally handsome. Muriel’s fashion-model looks must have completely turned his head. In a matter of weeks, he broke off his engagement to Margery and asked Muriel to marry him instead, and she accepted straight away.

I remember once gazing at Mum’s engagement ring, a square-cut sapphire set in white gold and surrounded by little diamonds. I asked if I could try it on and she

snapped, ‘No, you cannot. I had to work hard enough to get this ring and no one else is having it now.’

Who knows what kind of person Muriel pretended to be to enchant young Derrick Casey? The modelling shots she kept so carefully in the back of our albums show her statuesque and proud, her long neck and sculpted face a perfect foil for little pillbox hats with feathers on top, cartwheel straw hats or classic black toques. She’s slim as a gazelle but despite her beauty and elegance, she looks hard. You wouldn’t mess around with her.

No doubt she was sweetness itself in the run-up to her wedding and I suspect it was now that Muriel affected her act as a well-brought-up, church-going Christian girl. The Pittams weren’t religious at all, but the Caseys were staunch believers. It was important for Muriel to seem like the right sort of girl if she were going to be accepted as a member of the family and win Derrick’s affections. He was very devout, and often helped out at church fêtes and charitable events. No doubt Muriel seemed just as pious, although later, once she was safely married, she would dispense with formal religion and turn her own idea of God into a particularly dreadful weapon in her well-equipped arsenal.

Muriel and Derrick got married in 1941. The wedding photos are posed studio shots showing Mum with her hair swept up into a high style while she wears a dress of shimmering floor-length satin. She doesn’t smile in any of them but I can read a glint of triumph in her expression. She hadn’t just married into money; the Caseys were also very well connected socially. Now she could give up work and take her place in society as Mrs Derrick Casey, enjoying the dances and functions that they were invited to as a

couple. The photos show her enjoying the fruits of her marriage: she’s never in the same outfit twice and the albums are full of pictures of my parents partying and socializing, relaxing on the beach, or standing in front of Dad’s brand new Ford motor car. Muriel, with her modelling background, is always camera-conscious, adopting a pose of some kind, with hair flicked back and lips pouting. They look like everyone’s idea of the glamour couple – young, attractive, well-off and in love.

* * *

In 1949, Muriel’s success seemed complete. She was blessed with the arrival of a baby, my brother Nigel. In the family photographs, he is an angelic-looking little thing, with white-blond hair and a shy smile. Mum holds him on her knee, looking at him and smiling, her attitude relaxed.

It’s a different story in the pictures that follow. In those, she holds a plump, ruddy-skinned, scowling baby. She never looks at it and there’s an obvious look of disgust on her face. She resembles one of those people who secretly loathe babies and who try to hide their dismay after someone has plonked one down on their lap. She is angry, tightlipped and bored. The baby she is holding is me.

I arrived in 1950, the year after my brother, and it seems that right from the start, my mother was displeased with me. In my baby pictures, even the earliest ones, I appear nervous and uncomfortable. I’m not smiling in any of the photos, except one where I’m being cuddled by Nan Casey, Dad’s mother. I look wary and uncomfortable and often on the point of tears. What had happened to make me like that?

‘You were such a cry-baby,’ I remember Mum saying. ‘Nothing I did was ever good enough for you.’

* * *

But thousands of young mothers had the same experience as they adapted to their new lives caring for children and a home. They didn’t become what my mother became, and their children didn’t suffer what I was to endure at the hands of the woman who was supposed to love me best in the world. Something in my mother was so bitter and resentful that she became evil. It’s a strong word, but I can’t think of any other way to describe what she did.

The danger signs were there from the very earliest days, when Nigel and I were still very young.

My first serious injury occurred when I was eighteen months old. Mum had left me on a bed and I rolled off on to the floor, breaking my leg. That was the story, anyhow. But although I have no memory of what happened, I do remember our house. The bedrooms were thickly carpeted and the beds not high off the floor. I was a plump, well-

padded little thing. Would a roll from a low bed on to a soft carpet have been enough to break my leg? There were no witnesses, so I’ll never know.

There was a witness to another incident, though. Aunt Audrey told me that she glanced into the bedroom one night when Nigel was just one year old to see Mum holding a pillow over his face as he thrashed and writhed around.

‘Muriel, what on earth are you doing?’ she cried, rushing in to pull the pillow away.

Mum gave her a sharp look. ‘Sometimes it’s the only way to get him to stop crying,’ she said. ‘You know how I can’t stand listening to them cry.’

‘But he’s just a baby! You could kill him!’

Audrey said that Nigel’s breathing was very shallow and there was a blue tinge to his lips. Muriel shrugged and didn’t seem to take it seriously. Needless to say, Audrey made sure she never left any of her own children alone with Mum from that point on.

These things occurred before I was old enough to have any conscious memories. Once I do begin to remember, from around the time I was two years old, then the nightmare begins.