Purposes of Love (45 page)

Authors: Mary Renault

She lay, as she had always lain, on his left side. Without speaking he reached out for her, and drew her into the hollow of his arm. She came with a long sigh, her head slipping to his shoulder; he kissed her forehead.

It seemed then that she lay with the heaviness of sleep; but in a little while when his own eyelids were dropping, her voice stirred, hardly moving the darkness.

“Mic, I only wanted you to know, this is what I shall remember you by, always, after I’ve gone away. More than all the rest. Always.”

He made a sleepy questioning sound, the words only half penetrating his mind. “You’re not going away.”

“Yes. I’ve no right. I’ve nothing for you, Mic. I’m beaten.”

“So are we all,” he said, “in one way or another. Different ways, sometimes. That’s the use of being two.”

“You say that, my dear. You’re kinder than I thought anyone could be. But we know that isn’t enough.”

He laid his cheek against her hair. “I love you,” he said. “I’ve never ceased to love you.”

The words sounded strange in his own ears, for he was emptied of emotion, almost of thought. It was as if his spirit had spoken in a stillness within him.

For a moment she was quite still; then he felt and half saw the lifting of her head as she tried to look into his face. He stooped and kissed her on the lips. They stayed so for a little while; it was a long, strange kiss, without physical passion but curiously intent; they were too spent to know what they found in it, a communion or the taste of their private dedications.

Suddenly, as if a spell had been lifted, Mic looked up and said, in his ordinary voice, “Good Lord, I forgot to open the curtains. We shan’t get any air.” He slid out of bed and drew them back, letting in a faint not-darkness which seemed like light.

She opened the clothes to receive him back again. “Was it cold out there?”

“Feels like a frost.”

“What a shame,” she murmured drowsily. “Here.” She folded the warmth of her body against him, and almost at once they were asleep.

Vivian opened her eyes in the early light, dimly aware that some slight sound from Mic had aroused her; he had coughed, perhaps, or groaned at a sudden movement in his sleep. Whatever it was, it had not waked him. He lay with his face turned upward; at some time while they slept he had taken away the arm that had been around her, and crossed it, in subconscious defence, over the other that was slung to his chest. It was the posture of an effigy, calm and self-contained. Perhaps it was the watchfulness of his body, guarding its injury and forbidding him quite to relax, that had so dispelled the casual, almost childish abandonment in which he used to sleep, which had so often given her the sense of pathos, and, hardly realised, of her own power. In the grey glimmer of dawn she could see the contours of his face. There were changes of stress about the mouth and eyes, an indefinable shifting of shadows; traces of ill-health were there, but she noticed them, with a faint surprise, after the rest. It was the face, she saw, of a man and a possessor of himself. She knew, without joy or sorrow but in a motionless certainty, that he was the possessor of her self also.

Henceforward their relationship was fixed, she the lover, he the beloved. She believed that he would never abuse it, never perhaps wholly know it; he had a natural humility and he had his own need of her, not final like hers but implicit in him and real. She too would hide the truth a little; for there is a kind of courtesy in such things that love lends, sometimes, when pride has been destroyed.

But she would know always; it would always be she who would want the kiss to last longer, though she might be the first to leave hold; she for whom the times of absence would be empty, though she would often tell him how well she filled them; she who stood to lose everything in losing him, he who would have a little of the stuff of happiness in reserve.

In the secret battle which had underlain their love, of which she, only, had been aware with the mind, she was now and finally the loser. There were several ways in which she might partly have evaded the knowledge she brought to this moment. Half-truths might have sheltered her; that poverty had fought against her; that her work had demanded more of her than was just or than her life could afford; even that she was a, woman and had the fluid of submission in her blood-stream. But she knew that she could not surrender on any of these terms without dishonour. Mic had been right long ago: true or not true, that was not a basis on which life could be lived. There was an integrity which, illuminating defeat, could reflect in it the image of victory; and, embracing this, she acknowledged to herself that none of these things had settled her course. Like water she had found her own level; this was as it was, only because she had fought in the conscious craving for self-certainty and power, he in the simple instinctive reaching of his spirit for the good.

The sounds of the birds, dispersed and broken, was beginning, and the footsteps of the earliest workers rang at intervals, clear in the quiet and firm with their morning purpose, along the road. She turned softly on her side, in a position from which, without having to move again, she could lie and watch him; keeping her face pressed close to the pillow so that she might seem to be sleeping when he opened his eyes.

A Biography of Mary Renault

Mary Renault (1905–1983) was an English writer best known for her historical novels on the life of Alexander the Great:

Fire from Heaven

(1969),

The Persian Boy

(1972), and

Funeral Games

(1981).

Born Eileen Mary Challans into a middle-class family in a London suburb, Renault enjoyed reading from a young age. Initially obsessed with cowboy stories, she became interested in Greek philosophy when she found Plato’s works in her school library. Her fascination with Greek philosophy led her to St Hugh’s College, Oxford, where one of her tutors was J. R. R. Tolkien. Renault went on to earn her BA in English in 1928.

Renault began training as a nurse in 1933. It was at this time that she met the woman that would become her life partner, fellow nurse Julie Mullard. Renault also began writing, and published her first novel,

Purposes of Love

(titled

Promise of Love

in its American edition), in 1939. Inspired by her occupation, her first works were hospital romances. Renault continued writing as she treated Dunkirk evacuees at the Winford Emergency Hospital in Bristol and later as she worked in a brain surgery ward at the Radcliffe Infirmary.

In 1947, Renault received her first major award: Her novel

Return to Night

(1946) won an MGM prize. With the $150,000 of award money, she and Mullard moved to South Africa, never to return to England again. Renault revived her love of ancient Greek history and began to write her novels of Greece, including

The Last of the Wine

(1956) and

The Charioteer

(1953), which is still considered the first British novel that includes unconcealed homosexual love.

Renault’s in-depth depictions of Greece led many readers to believe she had spent a great deal of time there, but during her lifetime, she actually only visited the Aegean twice. Following

The Last of the Wine

and inspired by a replica of a Cretan fresco at a British museum, Renault wrote

The King Must Die

(1958) and its sequel,

The Bull from the Sea

(1962).

The democratic ideals of ancient Greece encouraged Renault to join the Black Sash, a women’s movement that fought against apartheid in South Africa. Renault was also heavily involved in the literary community, where she believed all people should be afforded equal standard and opportunity, and was the honorary chair of the Cape Town branch of PEN, the international writers’ organization.

Renault passed away in Cape Town on December 13, 1983.

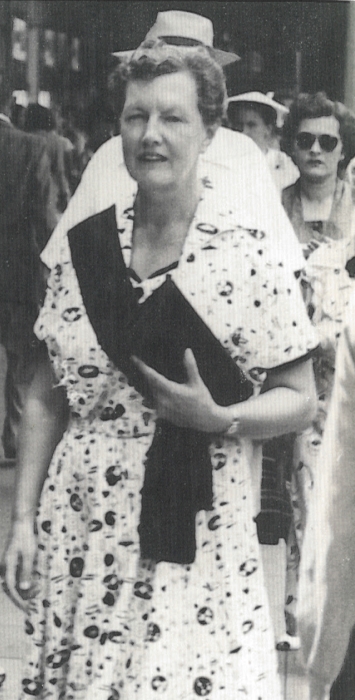

Renault in 1940.

Renault and Julie Mullard on board the

Cairo

in 1948, on their way to South Africa, where they settled in Durban.

Renault in a Black Sash protest in 1955. She was among the first to join this women’s movement against apartheid.

Renault and Michael Atkinson installing her cast of the Roman statue of the Apollo Belvedere in the garden of Delos, Camps Bay, in the late 1970s.

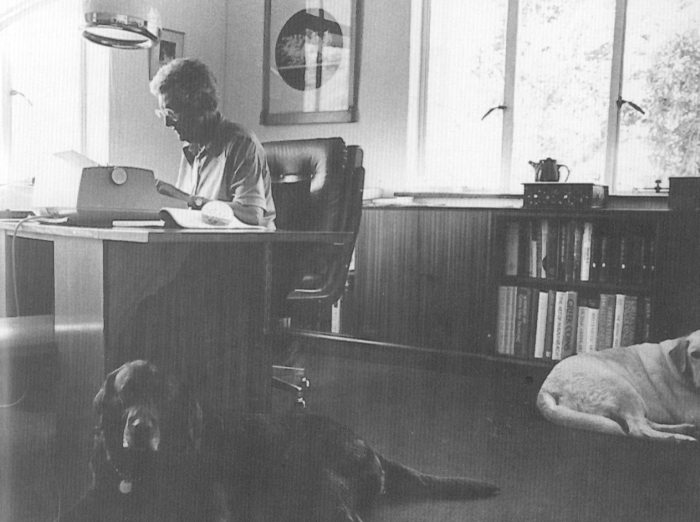

Renault working in her “Swiss Bank” study with Mandy and Coco, the dogs.