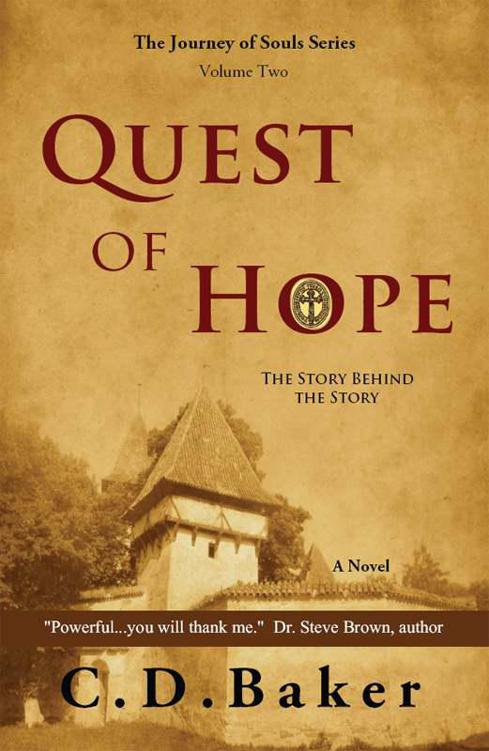

Quest of Hope: A Novel

Read Quest of Hope: A Novel Online

Authors: C. D. Baker

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Genre Fiction, #Historical, #Historical fiction

QUEST OF HOPE

© 2005 by C. D. Baker

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission, except for brief quotations in books and critical reviews.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-62111-044-6

This story is a work offiction. All characters and events are the product of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to any person, living or dead, is coincidental.

First Printing, 2005

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Printing/Year 09 08 07 06 05

Unless otherwise noted, Scripture quotations are taken from the

Holy Bible: New International Version

®

.

Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved.

To those humbled souls seeking grace

to endure the pursuit of Truth

Editor’s note: please find at the back of this book powerful discussion questions for group or personal study (Readers’ Guide, p. 479), as well as a helpful Glossary (p. 491) for clarification of terminology and historical information.

Contents

Book 1: Die Ordnung (The Order) 1174 – 1206

Chapter 4: Madonna and the Witch

Chapter 6: The Vow of the Worm

Chapter 8: Trials, Dreams, and Fear

Chapter 13: The Grindstone and A Gift

Book 2: Die Verwandlung (The Wandering) 1206 – 1212

Chapter 20: A New Journey Begins

I

am happy to express my gratitude to my wife, Susan, and the wide circle of family and friends who have offered supportive criticism and encouragement. The tale that follows would be very different without their good sense! I would like to thank my agent, Lee Hough, and my skilled editor, Craig Bubeck, as well as the many other enthusiastic professionals at RiverOak who have given life to this project. My heartfelt appreciation is extended to those whose unselfish support made my work more fruitful and enjoyable: my dear friends and distant cousins in Weyer, Germany; my old friend, Henk Haak of the Netherlands, who was a great help in Stedingerland; Father Vincenzo Zinno of S.

Maria in Domnica

Church and Mr. Constante Bucci, the curator of the

Sancta Sanctorum,

in Rome for their patience and generous hospitality; Joseph and Elisabeth Christ who labored over difficult translations; draft-copy critics such as my son David, my father and stepmother Charles and Elizabeth; and friends Mrs. Karen Buck, the Rev. Matthew Colflesh, and Mr. Edward Englert. Finally, let me thank Dr. Stephen Meidahl, Mr. David McCarty, and the Rev. Dr. Rock Schuier who, among others, contributed a wealth of spiritual wisdom, without which this story would be meaningless.

T

he hushed forests of Northern Europe stood like whispering sentinels keeping watch over the fog that shrouded the folk of legends and dreams until the legions of Rome climbed the Alps and nibbled at the edges of

Germania.

In due time the armies of the caesars subdued the clans of fair-skinned migrants dwelling there and seized what treasures they could find. As with all great empires, however, the Romans did more than just take for themselves. They blessed these lands with law, language, systems of administration, and means of commerce. And when the glory of Rome was laid to ruin, these gifts were left behind as a monument to her might.

Then, beginning in the fifth century A.D., another army eyed the lands of Europe. Traveling the very roads the Romans built, a small but brave band of light-bearers brought hope to a continent now covered in darkness. These determined soldiers were the spiritual descendants of St. Patrick and bore names like Columcille, Brendan the Navigator, and Columbanus. Called the “White Martyrs,” they sailed from the rugged shores of Celtic lands to bring the Gospel of Christ to the peoples of Europe.

The lasting influence of these Irish missionaries is immeasurable, for the peoples of Europe quickly cast aside their pagan gods and with them the terrors and bondage these gods imposed. No longer fearful of the earth, they plunged wheeled ploughs deep into the soil and built villages within the comforting shadow of stone monasteries. During this time of dramatic change, Christianity remained the common bond that connected the new order to the virtues of chivalry, courage, sacrifice, and loyalty. Submissive to the sovereigns of the land, devout men and women of sincere faith committed their lives to serving the needs of body and soul. It was the time known as the “Low Middle Ages.”

Cultures, like individuals, are inherently sown with the seeds of their own change. Each system of man’s genius is sprinkled with just enough flaws to germinate imperfection and, subsequently, discontent. It is no surprise, therefore, that a revolution of immense proportion occurred during the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries. Known as the Papal Revolution of Pope Gregory VII, it began with the twenty-seven theses of the

Dictatus Papae

issued in 1075. In political terms, the Revolution established the pope’s absolute supremacy over temporal rulers. In so doing, he inadvertently created a new realm known as “Christendom.” Under threat of eternal damnation, the rulers of Europe’s many kingdoms submitted their autonomy to the Church and, in so doing, yielded their armies as vassals of the pope.

With the knights of Christendom now at his disposal, the pope could strike a meaningful blow against the expanding Islamic empire. In 1095 Pope Urban called for the First Crusade, and over the next century subsequent popes and their subservient kings waged a violent defense of Christendom. The consequential influence of the Crusades requires volumes. Suffice it to say that seeds of change in Europe were well watered by the blood of Christian and Moslem alike. Transportation improved and commerce was enlivened. Fairs and huge markets for trade were created, as were systems of credit, banking, and insurance. New agricultural methods so significantly impacted harvest yields that the population surged.

It is these “High Middle Ages” that is the setting for the following story. It was an amazing time, for it was then that modern languages began to take their shape and when music began to move away from monophonic chants to take polyphonic form. Epic poetry, such as the

Song of Roland,

was written, and Bernard de Ventador touched hearts with his romance literature. Architecture began to reflect the spirit of the changing culture as well. Churches were no longer built with the squat, fortress-like characteristics of the Romanesque style, but rather in the triumphal confidence of the Gothic as expressed in Notre Dame and the Canterbury Cathedral.

Unfortunately, it was also an age that was in dire need of further rescue. Life was unspeakably hard. Pestilence, hunger, and violence were a part of everyday life. The lowly serfs suffered the most. They could not marry without consent, own land, freely leave the manor to which they were bound, nor avoid the confusing and weighty obligation of taxes, tithes, duties, and fines that maintained their poverty. Lacking liberty, health, and learning, this great host of souls languished through short, miserable lives in timid expectation of God’s imminent Judgment. Life was viewed as little more than preparation for death.

This story is a tale of common life in the Middle Ages. These ordinary events and seasons in the tiny village of Weyer, located in the very heart of Christendom, embrace dyers and millers, reeves and yeomen, housewives and witches. It was these simple folk who served their lords as the muscle and sinew of Western Civilization. So, though you shall encounter knights and lords, monks and merchants, it is the simple

Volk

with whom you shall break bread.

Under the guiding light of Truth, history is one of our greatest teachers. From the past we can learn much about hatred, vengeance, and loss; and much about love, forgiveness, and grace. It is wisdom that is the great gift of history, and what wisdom teaches us is that Hope is our faithful companion—even in the village of Weyer.

Veritas Regnare