Rats and Gargoyles (4 page)

Read Rats and Gargoyles Online

Authors: Mary Gentle

There are guides. They do not speak. They climb

narrow flights of stairs that wind up and around. The stairways are not lit.

Their fingers against the slick stone guide them.

Theodoret and Candia climb, ensnared in that

mirrored moment of midnight and midday.

"What are you doing here?" the black Rat demanded.

"My lord." Zar-bettu-zekigal bowed, the dignity of

this impaired by her hands being tucked up into her armpits for warmth. "We’re

students, passing through to the other side of the Nineteenth’s Aust quarter."

Lucas noted the black Rat’s plain cloak and sword-

belt, without distinguishing marks. A plain metal circlet ringed above one ear

and under the other; from it depended a black feather plume. The black Rat,

despite being unattended, had an air that Lucas associated with rank, if not

necessarily military rank.

"You’re out of your lawful quarter."

The Rat swept the last fragments of bone from the

niche into the sack, and pulled the drawstrings tight. His muzzle went up: that

lean wolfish face regarding Lucas first, and then the young Katayan.

"A trainee Kings’ Memory?" he recalled her last

words. "How good are you, child?"

The young woman lifted her chin slightly, screwed

up her eyes, and paused with tail hooked onto empty air. "Me:

What I like,

you haven’t got;

Lucas:

Really?

Me:

Really;

Lucas:

This

really is a short-cut?

Me:

Oh, right. Oh, right. You’re a king’s son.

Used to stable-girls and servants

—"

The Rat cut her off with a wave of one be-ringed

hand. "Either you’re new and excellent, or near the end of your training."

"New this summer." Zar-bettu-zekigal shrugged. "Got

three months in the university now, learning practical self-protection."

"I’ll speak further with you. Come with me."

"Messire—"

The Rat cut off Lucas’s belated attempt at

servility. "Follow."

They walked on into vaulted cellars, where the

loudest noise was the hissing of the gas-lamps. Soft echoes ran back from

Lucas’s footsteps; Zar-bettu-zekigal and the Rat walked silently.

A distant thrumming grew to a rumble, which

vibrated in the stone walls and floor. Bone-dust sifted down. The Rat carried

his ringed tail higher, cleaning it with a fastidious flick. His hand fell to

the small sack at his belt.

"Zari." Lucas dropped back a step to whisper. "Do

they practice

necromancy

here?"

"I’m a stranger here myself—!" The young woman’s waspishness faded. "The only good use for bones is

fertilizer. Who cares about fringe heresies anyway?"

"But it’s blasphemy!"

The Rat’s almost-transparent ears moved. He stopped

abruptly, and swung round. "Necromancy?"

Lucas said: "Not a fit subject for the location,

messire, true. Does it disturb you?"

The black Rat’s snout lifted, sniffing the air.

Lucas saw it register the sweat of fear, and cursed himself.

"Even were it a fit subject for our discussion,

necromancy–using the basest materials, as it does–is the least and most feeble

of the disciplines of

magia,

and so no cause for concern at all." .

The Rat drew himself up, balanced on clawed hind

feet, and the tip of his naked tail twitched thoughtfully. Metal clashed:

sword-harness and rapier.

"Who sent you here to spy?"

"No one," Zar-bettu-zekigal said.

"And that is, one supposes, possible. However–"

"Plessiez?"

The black Rat’s mouth twitched. He lifted his head

and called: "Down here, Charnay."

Lucas and Zar-bettu-zekigal halted with the black

Rat, where steps came down from street-level. The bone- packed vaults stretched

away into the distance. In far corners there was shadow, where the gas-lighting

failed. Dry bone-dust caught in the back of Lucas’s throat; and there was a

scent, sweet and subtle, of decay.

Zar-bettu-zekigal huffed on her hands to warm them.

The Katayan student appeared sanguine, but her tail coiled limply about her

feet.

A heavily built Rat swept down the steps and ducked

under the stone archway. Lucas stared. She was a brown Rat, easily six and a

half feet tall; and the leather straps of her sword-harness stretched between

furred dugs across a broad chest. She carried a rapier and dagger at her belt,

both had jewelled hilts; her headband was gold, the feather-plume scarlet, and

her cloak was azure.

"Messire Plessiez." She sketched a bow to the black

Rat. "I became worried; you were so long.

Who are they?"

She half-drew the long rapier; the black Rat put

his hand over hers.

"Students, Charnay; but of a particular talent. The

young woman is a Kings’ Memory."

The brown Rat looked Zar-bettu-zekigal up and down,

and her blunt snout twitched. "Plessiez, man, if you don’t have all the luck,

just when you need it!"

"The young man is also from"–the black Rat looked

up from tucking the canvas bag more securely under his sword-belt–"the

University of Crime?"

"Yes," Lucas muttered.

The Rat swung back, as he was about to mount the

stairs, and looked for a long moment at Zar-bettu-zekigal.

"You’re young," he said, "all but trained, as I

take it, and without a patron? My name is Plessiez. In the next few hours

I–we–will badly need a trusted record of events. Trusted by both parties. If I

put that proposition to you?"

Zari’s face lit up. Impulsive, joyous; cocky as the

flirt of her tail-tuft, brushing dust from her sleeves. She nodded. "Oh, say

you, yes!"

"Zari

. . ." Lucas warned.

The black Rat sleeked down a whisker with one ruby-

ringed hand. His left hand did not leave the hilt of his sword; and his black

eyes were brightly alert.

"Messire," Plessiez said, "since when was youth

cautious?"

Lucas saw the silver collar almost buried under the

black Rat’s neck-fur, and at last recognized the

ankh

dependant from it.

A priest, then; not a soldier.

Unconsciously he straightened, looked the Rat in

the face; speaking as to an equal. "You have no right to make her do this–yeep!"

His legs clamped together, automatic and

undignified, just too late to trap the Katayan’s stinging tail. Zari grinned,

flicking her tail back, and slid one hand inside her coat to cup her breast.

"I’ll be your Kings’ Memory. I’ve wanted a genuine

chance to practice for

months

now," she said. "Lucas here could practice

his university training for you!"

"Me?"

Her humor sparked outrage in him.

"You heard Reverend Master Candia. There

are

no rules in the University of Crime. Think of it as research. Think of it as a

thesis!"

Frustration broke Lucas’s reserve. "Girl, do you

know who my father is? All the Candovers have been Masters of the Interior

Temple. The Emperor of the East and the Emperor of the West come to meet in his

court! I came here to learn, not to get involved in petty intrigues!"

"Thank you, messire." Plessiez hid a smile. He

murmured an aside to the brown Rat, and Charnay nodded her head seriously,

scarlet plume bobbing against her brown-gray pelt.

"You’ll guest at the palace for two or three days,"

Plessiez went on. "I regret that it could not be under better circumstances,

heir of Candover. Oh–your uncle the Ambassador is an old acquaintance. Present

my regards to him, when you see him."

Zar-bettu-zekigal nodded to Lucas, thrust her hands

deep in her greatcoat pockets and walked jauntily up the steps at the side of

the black Rat.

"When you’re ready, messire."

Charnay’s heavy hand fell on Lucas’s shoulder.

As always, the height of the enclosed space jolted

him. Candia reached to grip the brass rail as they were ushered out onto a

balcony. The sheer walls curved away and around. Twilight rustled, shifted. The

darkness behind his eyelids turned scarlet, gold, black. A stink of hot oil and

rotten flesh caught in the back of his throat.

One of the servants clapped his hands together

twice, slowly. Sharp echoes skittered across the distant walls.

A kind of unlight began to grow, shadowless,

peripheral. Candia’s eyes smarted. In a sight that was not sight, he began to

see darkness: the midnight tracery of black marble, pillars and arches and

domes. Vaulting hung like dark stalactites. A rustling and a movement haunted

the interiors of the ceiling-vaults. The gazes of the acolytes that roosted

there prickled across his skin.

Pain flushed and faded along nerve-endings as a

greater gaze opened and took him in.

Hulking to engage all space between the

down-distant floor and the arcing vaults, the god-daemon lay. Black basalt

flanks and shoulders embodied darkness. Behind the Decan the halls opened to

vaster spaces, themselves only the beginning of the way into the true heart of

the Fane, and the basalt-feathered wings of the god-daemon soared up to shade mortal sight from any vision of

that interior.

Between the Decan’s outstretched paws, and on

platforms and balconies and loggias, servants worked to His orders: sifting,

firing, tending liquids in glass bains-marie, alembics and stills; hauling

trolleys between the glowing mouths of ovens. Molten metal ran between vats.

"My honor to you, Divine One." Candia’s voice fell

flatly into the air.

"Little Candia . . ." A sound from huge delicate

lips: deep enough to vibrate the tiled floor of the balcony, carried on carrion

breath.

Lids of living rock slid up. Eyes molten-black with

the unlight of the Fane shone, in chthonic humor, upon Candia and the Bishop.

The grotesque head lifted slightly.

A bulging pointed muzzle overhung The Spagyrus’

lower jaw. Pointed tusks jutted up, nestling against the muzzle beside nostrils

that were crusted yellow and twitched continually. Jagged tusks hung down from

the upper jaw, half-hidden by flowing bristles.

"Purification, sublimation, calcination,

conjunction . . . and no nearer the

prima materia,

the First Matter."

Down at cell-level, the voice vibrated in Candia’s

head. He stared up into the face of the god-daemon.

The narrow muzzle flared to a wide head.

Cheek-bones glinted, scale-covered; and bristle-tendrils swept back, surrounding

the eyes, to two small pointed and naked ears.

Theodoret leaned his head back. "Decans practicing

the Great Art? Dangerous, my lord, dangerous. What if you should discover the

true alchemical Elixir that, being perfect in itself, induces perfection in all

it touches? Perhaps, being gods, it would transmute you to a perfect evil. Or

perfect virtue."

The great head lowered. Candia saw his image and

the Bishop’s as absences of unlight on the obsidian surfaces of those eyes.

"We are such incarnations of perfection already."

Amusement in the Decan’s resonant tones. "It is not that alchemical

transformation that I seek, but something quite other. Candia, whom have you

brought me?"

"Theodoret, my lord, Bishop of the Trees."

‘

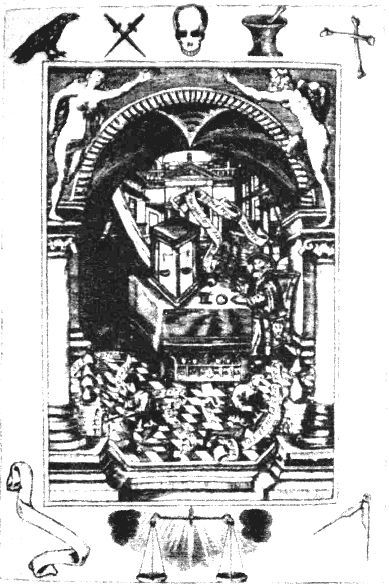

Purification, sublimation, calcination,

conjunction . . . and no nearer the prima materia

. . .’ Reconstructed from

an illustration in

Apocrypha Mundus Subterranus

by Miriam Sophia, pub.

Maximillian of Prague, 1589 (now lost)

"A Tree-priest?"

The unlight blazed, and imprinted like a magnesium

flare on Candia’s eyes the gargoyle-conclave of the Decan’s acolytes:

bristle-spined tails lashed around pillars and arches and fine stone tracery;

claws gripping, great wings beating. Their scaled and furred bodies crowded

together, and their prick-eared and tendriled heads rose to bay in a conclave of

sound, and the unlight died to fireglow.

"I will see to you in a moment. This is a most

crucial stage . . ."

On the filthy floor below, servants worked

ceaselessly.

The platform jutted out fifteen yards, overhanging

a section of the floor (man-deep in filth) where abandoned furnaces and

shattered glass lay. Here, the heat of the ovens built into the wall was

pungent.

"Take that from the furnace," the low voice

rumbled.

One of the black-doubleted servants on the balcony

called another, and both between them began to lift, with tongs, a glowing-hot

metal casing from the furnace. Sweat ran down their faces.

"Set it there."

Chittering echoed in the vaults. A darkness of

firelight shaded the great head, limning with black the foothill-immensity of

flanks and arching wings. One vast paw flexed.

"We reach the Head of the Crow, but not the Dragon.

As for the Phoenix"–unlight-filled eyes dipped to stare into the

alembic–"nothing!"

Candia said: "My lord, this business is

important—"

"The projection continues," the bass voice rumbled.

"Matter refined into spirit, spirit distilled into base matter, and yet . . .

nothing. Why are you here?"