Reading Financial Reports for Dummies (54 page)

Read Reading Financial Reports for Dummies Online

Authors: Lita Epstein

Inventory

As I discuss in Chapter 15, companies can use one of five different inventory valuation methods, and each one yields a different net income for the company. Inventory policy isn’t the only way a company can shift the value of its inventory on the balance sheet. Other common methods used include

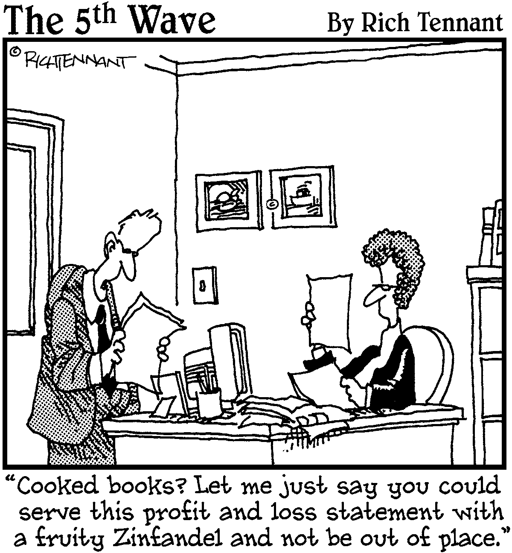

Chapter 23: Keeping Score When Companies Play Games with Numbers

311

✓

Overstating physical count:

Although this is absolute fraud, companies take this route to improve the appearance of their balance sheets.

Sometimes they alter the actual count of their inventory; other times they don’t subtract the decrease in inventory from the physical count.

Companies may also leave damaged goods in the inventory count even though they have no value.

✓

Increasing reported valuation:

Some businesses don’t even bother messing with their inventory counts. A simple journal entry increasing a firm’s inventory valuation and decreasing its costs of goods sold can improve appearances on both the balance sheet and the income statement. The assets side of the balance sheet looks better and the net income figure improves, too — which ultimately raises retained earnings to hide the existence of the journal entry and keep the balance sheet in balance.

✓

Delaying an inventory write-down:

Company management periodically writes down the value of their inventory when they determine that the products are obsolete or slow-moving. Because the decision to write down inventory is purely up to management, during a rough year, the company may delay writing down inventory to make its numbers look better.

Any time you suspect that inventory may be the object of financial game-playing, you can test your theory by calculating the number of days inventory sits around the company (I show you how to test the number of days inventory sits around in Chapter 15). Look for trends by running the numbers for the past three years. If you see that the number of days that inventory sits around gradually increases, definitely suspect a problem. The problem may not be creative accounting; it may be a sign of other problems, such as reduced consumer interest in the product or a bad economic market. The only way you’ll find out is to ask your questions to the company’s investor relations department.

Undeveloped land

Land never depreciates. But shareholders don’t have any details about where the land that a company owns is located, so they can never truly assess the value of undeveloped land on a balance sheet. This fact allows a lot of room for creative accounting and leaves the financial reader in the dark when it comes to finding this problem. Unfortunately, in a sketchy situation like this one, all you can do is wait for a whistle-blower to expose it.

Artwork

As is the case with undeveloped land, financial reports don’t detail the value of artwork that a company holds, so a lot of room exists for doctoring the numbers. Unless you’re looking at the financial statements for a company that regularly sells artwork, be wary when you see a large portion of its assets listed on the balance sheet in a line item called “artwork.” This line item shouldn’t be a major one for most companies that aren’t in the art business.

312

Part V: The Many Ways Companies Answer to Others

If you see a non-art business with a significant level of assets tied up in artwork, ask investor relations why the company is spending so much money on art. Frankly, a firm that ties up its money in art rather than using it to grow the business is not one I’d want to own stock in.

Looking for undervalued liabilities

Undervaluing liabilities can certainly make a company look healthier to financial report readers, but this deception is likely to lead the company down the path to bankruptcy. Games played by misstating liabilities frequently involve large numbers and hide significant money problems.

Accounts payable

Most times, an increase in accounts payable is directly related to the fact that the company is delaying payments for inventory. To test for a problem, you need to calculate the accounts payable ratio, which I show you how to do in Chapter 16. If you find a trend indicating that the number of days the company takes to pay its accounts payable is steadily increasing, test the number of days in inventory, as I show you in Chapter 15.

If the company fails both tests, investigate further. Even though the company may not be playing games with its numbers, take these signs as an indication of a worsening problem. With the trends you’re noticing, definitely call investor relations and ask for explanations about why the company has been paying its bills more slowly or why the inventory has been sitting on the shelves for longer periods of time.

If investor relations doesn’t answer the questions to your satisfaction, don’t buy the stock. If you already do own the stock, you may want to consider selling it if you believe the company is hiding the truth.

Accrued expenses payable

Any expenses that a company hasn’t paid by the end of an accounting period are

accrued

(posted to the accounts before cash is paid out) in the current period, so these expenses can be matched to current period earnings. This amount is added to the liability side of the balance sheet.

Unpaid expenses can include just about any expense for which the company gets a bill and has a number of days to pay, such as

✓

Administrative expenses

✓

Benefits

✓

Insurance

Chapter 23: Keeping Score When Companies Play Games with Numbers

313

✓

Salaries

✓

Selling costs

✓

Utilities

If the bill arrives during the last week before a company closes its books, the company most likely will accrue it rather than pay it. Most firms cut off paying bills several days before they close their books so the staff can concentrate on closing the books for the period.

If a firm needs to improve its net income, it can manage its numbers by not accruing bills and instead paying them in the next accounting period.

The problem with this strategy is that the next accounting period has more expenses charged to it than the company actually incurred during that accounting period. The expenses will be higher, and therefore, the net income will be lower in the next reporting period.

You can test for this particular game by watching the trend for accrued expenses payable. Check to see whether accrued expenses payable is going up or down from accounting period to accounting period. Usually, accrued expenses payable stay pretty level from year to year. If you see a steady decline, the company may be doing some creative accounting, or maybe the company’s decrease in expenses is simply due to discontinued operations or other changes. If you see a declining trend, look deeper into the numbers to see whether you can find an explanation. If not, call investor relations to find out why the trend for accrued payables shifts from accounting period to accounting period.

Contingent liabilities

Contingent liabilities

are liabilities that a company should accrue when it determines that an event is likely to happen. For example, if the company is party to a lawsuit that it lost and the winner was awarded damages, the company should accrue the liability as a contingent liability.

A company must determine two factors before it can list a contingent liability on its balance sheet. Factor one: The company deems it’s probable that it will be held liable. Factor two: The company can reasonably estimate the costs that will be incurred.

If the company hasn’t determined these two issues, you probably find a note about the contingency in the notes to the financial statements. Read the notes about contingencies and research further any items you think the company may not be fully disclosing. You do so by reading analysts’ reports on the company or by calling the investor relations department to ask questions about any issues mentioned in the notes to the financial statements.

314

Part V: The Many Ways Companies Answer to Others

Pay down liabilities

Another way that the firms involved in the scandals of the past three years played with their numbers was by indicating that they paid down their liabilities when they actually didn’t. To make its balance sheet look better, a company may transfer debt to another entity owned by the company, its directors, or its executives to hide its true financial status.

You probably won’t have any way of knowing if this is happening until a company insider decides to expose the practice or the SEC catches the company.

Playing Detective with Cash Flow

The statement of cash flows (which I discuss in detail in Chapter 8) is derived primarily from information found on a company’s income statement and balance sheet. You usually don’t find massaged numbers on this statement because it’s based primarily on the numbers that have already been shown on these other documents. But you may find that the presentation of the numbers hides cash-flow problems.

Discontinued operations

Discontinued operations occur when a company shuts down some of its activities, such as closing a manufacturing plant or putting an end to a product line. Many companies that discontinue operations show the impact it has on their cash in a separate line item of the financial report. Companies having cash-flow problems with continuing operations may not separate these results on their cash flow statements. Because the accounting rules don’t require a separate line item, this strategy is a convenient way to hide the problem from investors — most of whom don’t do a good job of reading the small print in the notes to the financial statements anyway.

If discontinued operations have an impact on a company’s income statement, you see a line item there listing either additional revenue or additional expenses related to the shutdown. You can find greater detail about those discontinued operations in the notes to the financial statements. Anytime you see mention of discontinued operations on the income statement or in the notes to the financial statements, be sure that you also see a separate line item in the statement of cash flows. If you don’t, use the information you glean from the income statement and the notes to calculate the cash flow from operations.

Chapter 23: Keeping Score When Companies Play Games with Numbers

315

To calculate the

cash flow from operations

(cash received from the day-to-day operations of the business, usually from sales), subtract any cash generated from discontinued operations (which you find noted on the income statement) from the net income reported on the statement of cash flows. When looking at a company’s profitability from the cash perspective, you want to consider only cash generated by ongoing operations.

When you take on the role of detective, you may uncover a cash-flow problem that the financial wizards carefully concealed because the rules allow such a misleading presentation. In Chapter 17, I show you numerous calculations for testing a company’s cash flow.

Income taxes paid

Just like with discontinued operations, the amount of income taxes that a company pays can distort its operating cash flow. The reason is that in some situations, companies pay income taxes as a one-time occurrence, such as taxes on the net gain or loss from the sale of a major asset. The income taxes a company pays for these one-time occurrences shouldn’t be included in your calculations related to operating cash flow.

By reviewing the sections on investing or financing activities in the statement of cash flows, you can find any adjustments you may need to calculate the operating cash flow. Here are two key adjustments you need to make to find the actual net cash from operations (the amount of cash generated from the company’s day-to-day operations):

✓

Gains from sales of investments or fixed assets:

If a company gains from the sale of investments or fixed assets (for example, buildings, factories, vehicles, or anything else the company owns that can’t be quickly converted to cash) that weren’t part of operations, add back in the taxes paid on a gain from the sale of an investment or fixed asset. Taxes paid on one-time gains distort the true cash flow from operations.

✓

Losses from sales of investments or fixed assets:

If a company loses from the sale of investments or fixed assets, the tax savings the company gets from the loss increases its cash flow. You need to subtract these tax savings from the net cash so your operating cash flow accurately reflects the cash available from operations.

316

Part V: The Many Ways Companies Answer to Others

Seeking information on questionable reporting

If you want to find more information about com-

AAERs detail criminal actions, civil actions, or

panies that may be playing games with their

cease-and-desist proceedings and how the

numbers, a good place to turn is Accounting

company or individual must correct their cur-

and Auditing Enforcement Releases (AAERs),

rent reporting practices. The AAERs also detail

posted on the SEC Web site. You can use the

any penalties the SEC imposes. To find the list of

search features to find any releases that the

current and past releases filed by the SEC, go to

SEC may have issued.

www.sec.gov and search for “AAERs.”