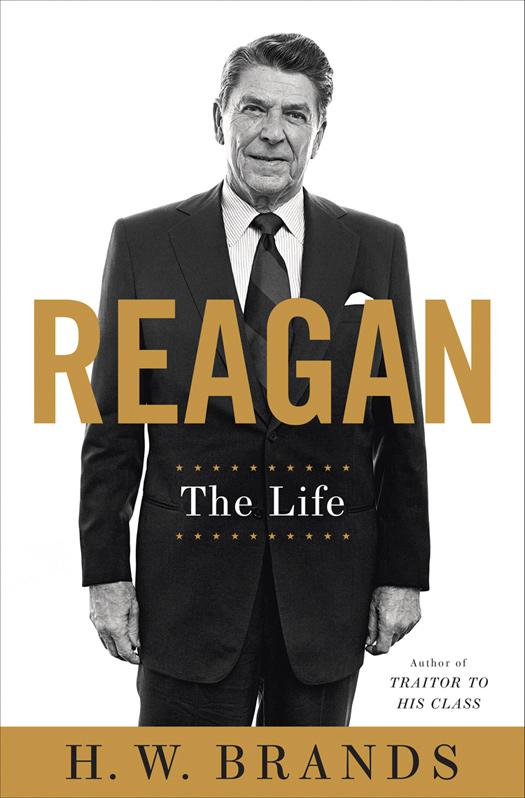

Reagan: The Life

Authors: H. W. Brands

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Nonfiction, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Retail, #United States

Copyright © 2015 by H. W. Brands

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., Toronto.

DOUBLEDAY

and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Photograph of the ABC story on the Reagan family

©

Bettmann/CORBIS

All other photographs courtesy of the Ronald Reagan Library

Book design by Michael Collica

Cover design by John Fontana

Cover photograph by George Rose/Getty Images

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brands, H. W.

Reagan : the life / H. W. Brands.

pages cm

ISBN

978-0-385-53639-4 (hardcover)

ISBN

978-0-385-53640-0 (eBook)

1. Reagan, Ronald. 2. Presidents—United States—Biography. 3. United States—Politics and government—1981–1989. I. Title.

E877.B73 2015

973.927092—dc23

[B]

2014038054

v3.1

TONIGHT

Don’t miss

“A Time for Choosing”

with

Ronald Reagan

9:30 to 10:00

WNBC-TV

Channel 4

Sponsored by T.V. for

Goldwater Committee

D

ESPERATE TIMES CALLED

for desperate measures. Barry Goldwater’s campaign was nearly broke, and the candidate was floundering. His opponent, Lyndon Johnson, the craftiest politician in the country, had wrapped himself in the mantle of the martyred John Kennedy to launch a revolution in civil rights and had portrayed himself as the coolheaded commander in chief to parry a communist insurgency in Southeast Asia. In the process Johnson had made Goldwater look like a closet racist and a trigger-happy warmonger. Goldwater hadn’t helped his cause by calling himself an extremist, albeit in the defense of liberty, and by suggesting that nuclear weapons be used in Vietnam. The more he spoke, the deeper his hole grew and the more remote his chances of victory. In his desperation, a week before the election he turned to a proxy speaker, a political unknown from California, Ronald Reagan.

Reagan faced desperation of a different kind, less public but more

protracted. A washed-up actor last seen hawking the wares and bromides of corporate America, Reagan was at a turning point in his life. As a child he had discovered the allure of an audience, the soothing effect of applause on one’s anxieties. He stepped from the stage of church skits and school plays to broadcast radio, which multiplied his audience into the hundreds of thousands, and then to movies, which put his face and voice before millions. But in Hollywood he hit the limits of his talent. He never captured the movie-house marquees, never cracked the A-list of leading men. By his mid-thirties he couldn’t get good roles. He moonlighted in the politics of the film industry, representing actors in negotiations with the studios. But that gig ran out, and he was hard up for work. He took a job with

General Electric that got him back on-screen, but the much-reduced screen of television, in the much-reduced role of series host. His contract required him to schlep the country for GE, speaking to company employees and to local business boosters about the blessings of big industry and its essential role in the American dream. His own dreams meanwhile faded, and when the GE job ended, they all but disappeared. The invitation to speak for Barry Goldwater came as a godsend, but one fraught with risk. It put him before an audience again and gave him a chance to be heard, but he knew if he flubbed this opportunity, he might never get another.

The Goldwater campaign didn’t expect much. It bought a single-column notice on page 79 of the October 27 issue of the

New York Times

; comparable ads ran equally deep in papers around the country. In 1964 political campaigns were still figuring out how to employ television. They hesitated to use spot advertising, from fear that they would be seen as packaging their candidates like cereal or cigarettes. In this case the Goldwater campaign created a faux political event. It hired a hall in Los Angeles and enlisted a few hundred supporters who received Goldwater placards and signs. It placed Reagan on a podium draped in bunting the television audience took for red, white, and blue, though the broadcast was in black and white. He spoke as though at a campaign rally of the sort that had characterized American politics for more than a century.

But this staged event lacked the spontaneity of a genuine rally, and the speech started awkwardly. The audience awaited its cue, the name Goldwater, but Reagan spoke for many minutes before mentioning the candidate, and the audience sat mute. Reagan nervously talked too fast. His standard speech for the GE circuit was longer than this evening’s television time allowed, yet rather than edit it down, he tried to pack it all

in. The silence of his listeners caused him to talk through his laugh lines, making the awkwardness worse. During his years with GE he had abandoned the pro-government liberalism of his young adulthood in favor of a pro-business conservatism; in doing so, he accumulated note-card decks of statistics documenting government waste and excess. On this occasion he rattled the statistics off in numbing order. Then, without warning, he swerved from domestic politics to foreign policy, leaving his audience confused as to what the American federal debt had to do with the Castro revolution in

Cuba. His gestures didn’t suit his words, and his principal gesture, a wagging of the right index finger, looked decidedly schoolmarmish.

Yet something happened midway into the half-hour speech. A belated mention of Goldwater got the crowd to respond, and their encouragement calmed Reagan down. He gave his jokes their moments to sink in. “

Anytime you and I question the schemes of the do-gooders, we’re denounced as being against their humanitarian goals,” he said. “They say we’re always ‘against’ things—we’re never ‘for’ anything. Well, the trouble with our liberal friends is not that they’re ignorant; it’s just that they know so much that isn’t so.”

The audience perked up the more. American conservatives were a combative tribe who didn’t speak of liberals as their “friends,” but here Reagan did. His tone was serious, but it wasn’t angry, the way Goldwater’s often was. Reagan criticized Democratic leaders, but he didn’t criticize Democrats. He condemned the direction the American government was going, but he professed confidence in the American people.