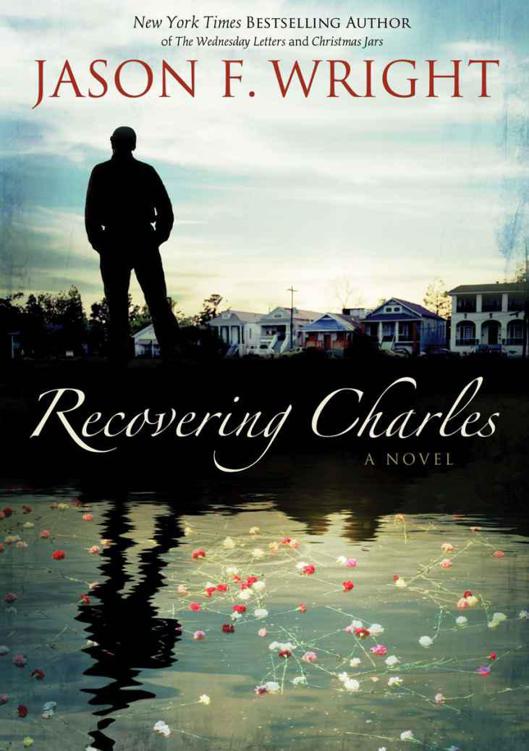

Recovering Charles

“Love Me if You Can” music and lyrics by Cherie Call © 2008 Mendonhouse Music (ASCAP). Used by permission. http://www.cheriecall.com

© 2008 Jason F. Wright

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, Shadow Mountain¨

. The views expressed herein are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the position of Shadow Mountain.

All characters in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Visit us at ShadowMountain.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wright, Jason F.

Recovering Charles / Jason F. Wright.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-59038-964-5 (alk. paper)

1. Fathers and sons—Fiction. 2. Adult children—Fiction. 3. New

Orleans (La.)—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3623.R539R43 2008

813'.6—dc22

2008018859

Printed in the United States of America

R. R. Donnelley and Sons, Crawfordsville, IN

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

To Kodi

I’d swim through a hurricane for you

Prologue

Present Day

I can’t look up without seeing it.

But it’s not there by chance. It’s precisely centered on the wall opposite my desk. Blown up in black and white. I cannot escape it. Framed in imported Japanese wood more expensive than the laptop I use to write my story. It’s just one of the thousands of pictures I’ve taken in the last decade. Maybe hundreds of thousands.

But only one hangs on the wall facing my desk.

A small, faceless crowd at a distance. A figure on a nearby sidewalk dressed in a white suit. A plain wooden casket with only a few flowers. Two men playing saxophone, one more on trumpet, one on trombone. One woman singing at the front of the marching caravan, one more twirling a parasol, and two more simply following along.

In a life tattooed by mistakes and heartache, both inflicted and received, the photo symbolizes my most treasured accomplishment and the anguish it caused me.

And it means more to me than the Pulitzer it won.

~ ~

Charles Millward was born a brilliant musician.

Not exactly a brilliant

player

of music, but a remarkable musician all the same. He once told Mr. Dalton’s fifth grade class on Parents’ Day that if you listed America’s top ten thousand saxophone players he wouldn’t make the list.

“Now kids, if the list

only

includes men who play the sax, and

only

men born in January, and

only

those with four smelly toes on their left foot because the fifth never popped out while I was cooking in Luke’s grandma’s belly, then I

might

make the list . . .”

The kids laughed.

“But,” Dad added, “

only

if you made it the top ten thousand

and one.

”

The kids laughed even harder, and I grinned in the big cheesy way that only a 5th grader totally enamored with his father can.

Then came Dad’s punch line. “And I’m the

and one.

”

No, Dad’s fat, clumsy fingers didn’t love the sax as much as his heart ever did. In college he was self-taught on guitar and could find his way around almost any instrument. And though he became quite good on the piano, enough so he could survive on tips at local bars, I think his soul loved playing the sax most.

He heard music when others didn’t. We learned through the years that Dad even

thought

in musical notes. Mom said he spoke that way too, in meter, with an ebb and flow, pausing, building strength, a crescendo, a long finish. A deep breath.

I always wondered if he read music the way I looked at photos, or like Pavarotti sang, Michelangelo sculpted, or Orson Welles made movies. Even as a child I remember noticing Dad’s eyes dance from note to note as he played the songs he had scribbled in a ragged leather journal held together by two fat rubber bands.

Sometimes at night he’d bring in his journal and his guitar and play me a song at the foot of my bed. The sax was his most prized possession, though his Gibson acoustic wasn’t far behind. I didn’t care that his voice would often crack and fall. The melodies sold the songs.

“Every note tells a song’s story,” Dad liked to say. “And every song, no matter how short, has a second verse. You just have to find it.”

It took me a long time to learn what Dad meant. I don’t think Mom ever did.

Still, I do think she loved my father.

Except when she was high.

~ ~

The doctor first prescribed sleeping pills for my mother in June of 1990.

They worked.

Mother slept through the rising temperatures of Fort Worth, Texas, through our cul-de-sac’s Fourth of July celebration, and into the dog days of August.

The country prepared for war in Iraq.

Dad watched.

Mom slept.

And Dad never left her side. Not when his job at one of the country’s top architectural firms was threatened. Not when the sleeping pills didn’t satisfy her anymore and he discovered Vicodin in an Advil bottle on her nightstand. Not even when she begged him to take me far away and let her fade from this life.

“I won’t,” he said.

My father clung to his complicated, braided rope of faith. He said one day Mother’s soul would surface again and she’d return to the elementary school and the students she once loved.

The girls made her construction-paper cards with white tissue-paper flowers glued to the front. The boys made cards, too, adorned with blue Dallas Cowboy stars and football helmets.

Everyone missed Mrs. Millward.

But no one ached for her like Dad.

I’ve seen every Sunday night, inspirational made-for-TV movie where towering heroes in death’s grasp never give up their positive attitudes. They somehow muster the strength to encourage others to love more, to forgive, to live their lives better. Jack Lemmon died that way in

Tuesdays with Morrie,

so did Ronald Reagan playing Gipp in

Knute Rockne: All American.

Optimism. Spirit. Readiness for whatever hides just beyond the light.

I wish that had been Mom. Just one year after Grandma’s accident, Mom took every pill she could find, including some Dad had locked in his den, and took a nap she hoped would be her last.

Dad found her dead in their bed.

Her head was under her pillow, hiding from the world even at the very end.

She left the world bitter and cursing. She cursed the pharmaceutical companies for making the drugs that stole her will. She cursed the doctors she’d begged to prescribe them. She cursed God for making her dependent on pills. She even cursed Dad for not leaving and making a better life for the two of us.

Mom died hating her husband and his premonitions, hating the rain, Mexicans, the sun, her therapist, mornings, Sundays, Barbara Walters, and sometimes me.

But mostly I think she just hated God.

Four days later, at her funeral, a dozen mourners passed by her casket and whispered good-byes and condolences. They thought she looked at peace. So warm and restful.

I thought she looked every bit as cold as she had the last year of her life.

I’ll never forget Dad’s unfinished eulogy. His voice cracked as he began reading the lyrics to a song he’d written for Mom during their courtship. He made eye contact with me and began to weep. He covered his eyes with one hand and pounded the other on the pulpit so hard it tipped to the right and almost toppled. His word-for-word remarks, scribbled on white 5x7 cards, scattered on the floor.

Dad’s best friend, Kaiser, a man he’d worked with side by side at their firm, gathered up the cards, put them back in order, and finished the eulogy.

Kaiser read about Mom and Dad’s first meeting at a science fair in high school, about Dad’s premonitions, their joy at my birth, the hole in his heart that wouldn’t be healed until he saw her in the house he’d some day build for them in heaven.

When Kaiser finished, he set the cards aside and added some impromptu words of his own. He thanked my father for his years of friendship and pledged to stand by him the way Dad had stood by Kaiser during some challenging times of his own.

“Ladies and gentlemen, Charles Millward has been there for all of us. He was there for me when I almost lost my job a few years back. He defended my honor when others at work wouldn’t. There’s no other way to say it, he saved my bacon.” Kaiser pulled a handkerchief from his pocket and blew his nose hard three times, getting louder with each honk.

Someone’s little boy in the back row giggled before his mother’s hand clamped across his mouth.

“You all know it’s true,” Kaiser continued. “Charlie would walk to the end of the longest road in Texas to help anyone here. He was there for his wife when life got so hard none of us could imagine it. It wasn’t easy for Charles to watch his dream girl, his one true love, struggle through this last year. But he was there no matter what.” Kaiser looked at Dad and seemed to wait until the rest of us were looking at him, too. “Now it’s our turn to be there for him.”

Dad slumped into the chair next to me on the front row, and I draped my arm awkwardly around him. His body shook.

I cried, too, but mostly for Dad.

The next decade and a half passed by like a Texas thunderstorm. Lightning quick. Not enough rain.

~ ~

Today is like any other in our microscopic Manhattan studio apartment. I’m alone. Around me and within easy reach are my four angels: my 35-millimeter old-school camera (a Canon EOS 1v), a ridiculously expensive digital (a Canon 5D), my baby

(a MacBook Pro), and my sweet Jesse (a saxophone).

Meanwhile, my real-live angel is almost certainly sitting at her City Hall desk arguing with her cubical-mate about Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens or last year’s World Series. In between rounds they will cooperate long enough to write grants and chase music education funding for the city’s more than six hundred elementary schools. She will twist arms, use more salt than sugar, offer to pick up a check personally at their home if necessary, insist on e-mailing an MP3 file of a recent concert at the Brooklyn Music School.

She’s not trained in this field, but she’s become an expert anyway. And she’ll win. She always wins.

Tonight at home she’ll playfully gloat and tease me about my desk. It’s an organized mess. Invoices, photos, proof sheets, and catalogues sit in staggered stacks near the back edge in a line. They hang an inch off the edge, daring my feet to kick them to the floor like heavy broken parachutes for the second time this afternoon.

I’ll remind her of my favorite NYU professor’s theory: Desks were made for propping up feet. Most of Larry’s lectures were given from his squeaky chair at the front of the mini-auditorium, and his feet, shoeless but always hidden in navy blue dress socks, rested on the front edge of his desk as he lounged backward.

Larry is a good man. It’s no stretch to say I learned everything I know about the eternally intimate relationship between life and the lens from that man. That was his phrase, “eternally intimate.”

“Luke Millward owes his career to Larry Gorton.” At least that’s what my colleagues say when they see my work in

National Geographic,

Time,

or on the front page of a top-fifty newspaper. They’re right.

After all, Larry’s the one who talked me into going to New Orleans.

Part

1

Chapter

1

Monday, August 29, 2005

New Orleans was underwater.

The storm had come; the one the Gulf had always feared. Hurricane Katrina brushed Florida as a Category 1, killing eleven and leaving a million in the dark. Then it strengthened over the ocean and made landfall twice more, unleashing its fury on the Gulf Coast like a woman scorned. No mercy. Thousands fled before impact; thousands more stayed.

The footage was numbing.

Fats Domino was reported missing. So, too, were countless other musicians who had built the city but whose names we wouldn’t know.

The French Quarter was mostly spared the flooding, but blocks away the water had baptized homes, businesses, nightclubs, and the homeless.

Fox News’ Shepard Smith was standing on Canal Street. He tossed the segment to an unrecognizable reporter three miles away who was on a small fishing boat in the Lower Ninth Ward. The reporter gestured to a body twenty feet away—facedown, arms and legs spread out, like an upside-down snow angel. “It’s hard to imagine what these people endured in their final moments. Impossible. Back to you, Shep.”