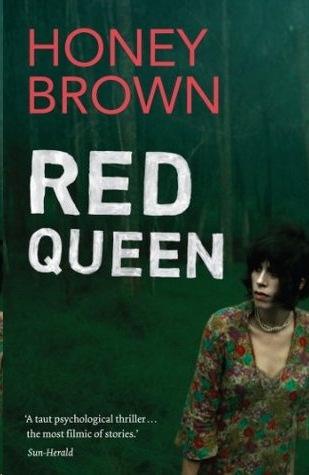

Red Queen

RED

Q

UEEN

Honey Brown lives in country Victoria with her husband and two children, and together they run a small flock of sheep.

Red Queen

is her first novel.

H.M. BROWN

RED

Q

UEEN

VIKING

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (Australia)

250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada)

90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Canada ON M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland

25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd

11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ)

67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd

24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published by Penguin Group (Australia), 2009

Text copyright © H.M. Brown 2009

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The extract from ‘The Listeners’ by Walter de la Mare is reproduced with permission of the Literary Trustees of Walter de la Mare and the Society of Authors as their representative.

ISBN: 978-1-74-228654-9

THE

N

OTE

1

I HAD COME

to know every line in my brother’s face. I didn’t want to know another man’s face in such detail – even my brother’s – but months alone with him and I knew how his hair would fall if he turned his head a certain way, the muscles that would draw up with a smile, the lashes that would come together if he fixed me with a stare, and the arrogant tug that lived in the corner of his mouth. I knew his face better that I knew my own. He was all I had to look at.

You would think then that in a game of cards I would be able to call his bluff.

I couldn’t.

We were sitting in front of the open fire in the lounge room, each in our high-back armchairs with a small card table between us. The stone walls and timber beams of the cabin were illuminated by the firelight. During the day the room was dust-choked and unused, at night it came alive with flame and shadow.

‘What you thinkin, Pup?’

I straightened in the chair and took a final quick look at my cards. ‘Nothing. Here – you win.’

The scattered low clubs and diamonds settled across the table. Rohan bent over my cards, frowning in the dim light to see them. ‘Will you look at that,’ he murmured.

I leant closer. ‘What?’

‘You really were thinking nothing.’

He got to his feet, ignoring my dark look up at him. Beside the glass of water on the table was his neatly stacked hand. I gathered the cards together, my fingers edging towards the stack.

‘I wouldn’t look if I were you,’ he said with his back to me. ‘Throw in the towel like that and you don’t deserve to know.’

I took his cards, tapping them into the pack without looking at them. The Browning shotgun was leaning against Rohan’s chair, shining henna in the light. The connection I felt to it was surprising – the weight of it, every smooth line, the hard metallic smell under a buffer of well-oiled warmth. Rohan picked it up and passed it to me. I glanced into his eyes – saw that the knowing glint was back. It was near impossible to hold Rohan’s gaze in these instances – as if he could see right into you, isolate raw qualities you yourself didn’t like to spotlight.

‘Be on your toes tonight. Full moons are always trouble. Don’t play that bloody guitar, and keep a proper lookout. And don’t go near the fridge.’

I laid the gun across my lap. ‘Jesus, I can’t believe you’re still going on about that.’

‘Don’t go near the fridge.’

‘But I’m telling you – I’ve told you, I didn’t take the meat. Why can’t you believe me? Why would I lie?’

‘I don’t know why you’d lie. That’s the stupidity of it – if you’re gunna lie, at least do it with some brains and balls.’

‘I could say you took it.’

He turned away.

‘Well it’s the same thing as what you’re doing to me. Listen – I did not touch the meat. It was in the fridge when I put the fruit away and that’s all I know. I walked through the kitchen once during my whole watch and I didn’t even open the fridge.’

‘So how exactly do you explain it disappearing then? Possums got some sort of dexterity I’ve not wised up to?’

‘I don’t know. Perhaps you did it in your sleep.’

‘No – you’re the dopey sleepwalker.’

‘Sometimes things happen that can’t be explained – that doesn’t mean you just point the finger at me.’

‘That’s interesting, coming from you.’

I pushed to my feet and walked towards the French doors. The barrel of the gun butted insistent against my hip and the thick leather strap creaked near my ear. ‘I didn’t take the fucking meat,’ I said, and shut the door behind me.

Moonlight illuminated the sheep between the trees and the nervy mob of roos that came through every night. Koalas growled and snorted like feral pigs in an echoing ogre anthem. I could feel Rohan’s wakefulness, could picture him curled on his side, fully clothed, maybe with boots on, staring into the shadowy corners, his head full of pessimism. Still, it was hard to begrudge him it – you had to fill your head with something.

Picking out Ry Cooder’s ‘13 Question method’ on the acoustic and croaking a baleful attempt at the lyrics, I filled my head with the steely notes. I didn’t consider myself any less aware even though I curved my back around the guitar and looked down to watch my fingering.

The brazen weight of a mouse on the toe of my boot shifted my concentration; my fingers stopped on the strings. The mouse moved away, across the boards and over the edge of the veranda.

I shivered.

Cold.

With a fortifying breath I stood and sat the guitar in the wicker chair beside me. Inside, I pulled back the curtains and left the door open – the cabin could do with some fresh air. It also made the decision to leave the gun against the stonework seem less reckless.

I walked into the kitchen. It smelt of cold fat and charred meat. The benches were timber with a glossy coating of lacquer. While other rooms in the cabin had their modern touches, the kitchen remained rustic right to its back teeth; Dad’s logic had been to keep the vital parts of the cabin rudimentary and technology free. Even the sink was old-world and enamel.

Spread respectfully from one end of the bench to the other was the gleaming oiled sides and black handles of a full set of knives and sharpening steels. It was odd that Rohan hadn’t put them away. I took the towel from the end of the bench and laid it flat; I set each knife out on the material.

On the floor at my feet was the canvas bag the knives were kept in. I frowned down at it. Normally it would be folded on the bench.

I slid the knives into the bag and put them in the cupboard.

The fridge was the one exception amongst the provincial surrounds; it hummed with the constant trickle of power from the water wheel at the bottom of the bluff. Something made me check inside it. The interior globe was blown and I had to peer to see the shelves. I lifted the top plate covering that night’s leftovers. One chop was missing, and maybe a pear from the metal colander below. The fruit was not as prized as the meat. I knew the specific chop that was gone.

It was while shutting the fridge door that I heard it – a noise from the lounge room. For a frozen moment I bent my head and tried to categorise it. The cabin was always uttering its midnight sounds: possums in the roof, the beams and gables expanding and contracting, but this one sounded like … a stifled sneeze. Yet the silence that followed it left me sure all I’d heard was an ember popping in the fireplace.

Rohan slept in the main bedroom, down the hall, opposite the bathroom and toilet. The walls of the hall were mosaic with photo frames and their grinning images. The result of so much joyous memory tacked up at eye level was the tunnelling of vision, or bowed-head floorboard gazing, the latter of which I did now – not that I could see the photos in the dark, but it paid to keep things regimented.

Rohan’s bedroom door was ajar. It was lighter in his room, the curtains were half-drawn and a rectangle of light stretched across the bed. Rohan lay on his side, facing the door, eyes open, with the Sako rifle beside him.

‘What is it,’ he said without lifting his head from the pillow.

‘You took it.’

‘What?’

‘The meat. There’s another chop missing – you had it before you came to bed. And you left the knives all over the bench. It’s not even my bloody rule —’

Rohan sat up and swung his legs from the bed; he had his boots on. ‘I put the knives away. Where’s the shotgun?’

I looked down at my hands as if I might see it. ‘It’s out on the veranda. I was just coming in to get my coat.’

Rohan brought the rifle to his shoulder and aimed it at the black space of the hall behind me. His pose was so deliberate and combative I struggled with the moment.

‘Were there any knives missing?’ he asked.

‘I don’t know … I think … maybe the small one.’

‘You put them away?’

‘Yes.’

‘Stay behind me.’

With the gun hard to his shoulder, Rohan sidestepped into the darkness. I caught a glimpse of the wild-white of his eyes and was close enough to understand the depth of his anxiety. It was the isolation – just the two of us, no emergency number to call, no neighbour to hear, no community, no society, no law. Rohan pulled up the neck of his jumper to cover his nose and mouth; he nodded at me to do the same.

The necessity to get to the veranda and check to see if the shotgun was gone gave us some impetus. The expanse of outside was equivalent to a deep calming breath. And even as I saw the shotgun was gone I had a sense of undefinable release; maybe it was that the worst possible situation was realised. I’d failed my brother at such a fundamental, life-threatening level it was only up from here.

Rohan had pulled his jumper from his face and was looking at me with the question of where the gun had been clear in his tight black eyes. I let my jumper fall around my neck and looked pointedly at the empty patch of wall.

‘It’s gone,’ I whispered.

The words hung a moment before Rohan looked away, his face made soft with disappointment; it was more unnerving than his anger, and before the muscles firmed back into something more like Rohan Scott, they softened further into total slack-faced bewilderment. He may have even prayed, his face tipped to the grey light of the moon and the rifle pointing up beside him.

He turned to me. ‘We die,’ he hissed through clamped teeth. ‘We die because you couldn’t do the simplest thing.’

I crossed my arms and gripped each bicep hard enough for the pain to register. Rohan looked away again, as if the answers were out there drifting in and out between the trees.