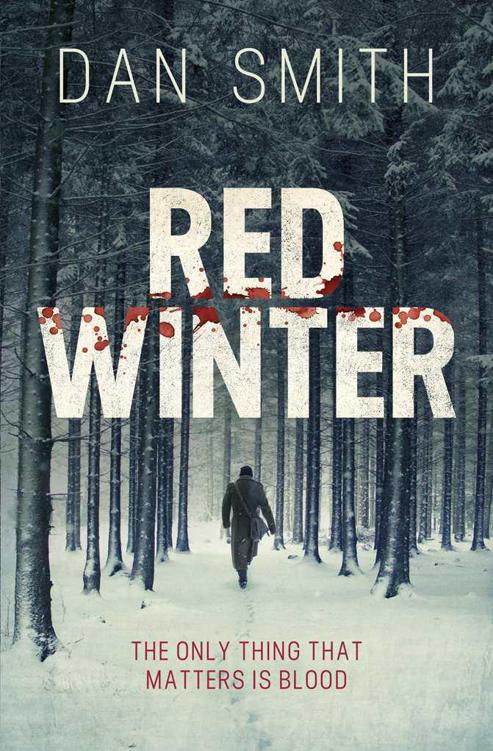

Red Winter

Authors: Dan Smith

RED WINTER

Dan Smith

For Helen and Laura

Bringing a novel to the shelves is no small matter, and no writer can work in total isolation. So thanks go to my agent Carolyn for all her advice and hard work, and to Jon, Eli, Laura, and all the other talented people at Orion who have had a hand in giving life to Kolya’s story.

Thanks also to my wife and children who put up with my vacant looks when my mind is elsewhere and are always ready to offer a first opinion and a reassuring word when it’s needed.

Once upon a time there was a smith.

‘Well now,’ says he. ‘I’ve never set my eyes on any harm. They say there’s evil in the world. I’ll go and seek me out evil.’

So he went and had a goodish drink, and then started in search of evil. On the way he met a tailor.

Well, they walked and walked till they reached a dark, dense forest. In it, they found a small path, and along it they went – along the narrow path. They walked and walked, and at last they saw a large cottage standing before them. It was night; there was nowhere else to go.

In they went. There was nobody there. All looked bare and squalid. Presently in came a tall woman, lank, crooked, with only one eye.

‘Ah!’ says she. ‘I’ve visitors. Good day to you.’

‘Good day, grandmother. We’ve come to pass the night under your roof.’

‘Very good. I shall have something to sup on.’

Thereupon they were greatly terrified. As for her, she went and fetched a great heap of firewood, flung it into the stove and set it alight. Then she went up to the two men, took one of them – the tailor – cut his throat, trussed him and put him in the oven.

From

One-Eyed Likho

, a traditional

skazka

, translated by W. R. S. Ralston

The village cowered with doors closed and windows shuttered. The street was empty. The cold air was quiet.

Kashtan sidestepped beneath me, shaking her head and blowing hard through flared nostrils. I leaned forward and rubbed her neck. ‘You feel it too, girl?’

There should have been voices. A dog barking. Women coming in from the field. There should have been children, but I heard only the wind in the forest behind and the murmur of the river before me.

I stayed in the trees and watched the village, but nothing moved.

‘You think they’re hiding from us?’ I spoke to my brother. ‘Or do you think . . . ?’ I stared at the back of his head and let my words trail away. ‘I promised to get you home, Alek. Look.’ I raised my eyes once more and studied the log-built

izbas

across the river. ‘Home.’ But there was no light in any of the windows.

Kashtan moved again, something making her uneasy.

‘Come on.’ I nudged her forward into the water. ‘Let’s have a look.’

I knew I should have waited until dark, but I’d been travelling a long time. For days we had kept to the trees to avoid the colourful armies that had battled over our country in civil war since the revolution, and now the people from my dreams needed to be made real. I had to reassure myself that my family wasn’t an illusion; that I hadn’t imagined them just to give everything a purpose.

Somewhere a crow called into the darkening afternoon and I snatched my head up in the direction of the sound. For a moment I saw nothing; then a black shape rose from the bare fingers of the tallest tree behind the houses. It wheeled and dived, skimming the wooden roofs before it passed over me and disappeared from view. I took one hand from the reins and rested it on my thigh, close to the revolver in my pocket. The mare faltered, reluctant to enter the cold river, but I encouraged her into the shallows, where she struggled to find her footing on the stones below. I pressed her on until my boots were soaked through, but as the water swelled round my knees, leaching my warmth and carrying it away towards the lake, Kashtan tossed her head and stopped in the deepest part as if she had come to an unseen barrier. She wanted to turn, to be away from here. She had scented something that troubled her.

‘What is it?’ I said, looking at Alek, but he gave no answer. ‘Come on, girl.’ I spurred Kashtan into motion. ‘Don’t give up on me now.’

We came out onto the bank close to the windmill and passed beneath the sails, leaving a dark, wet trail in our wake. Kashtan’s hooves were hollow on the hardened dirt of the track, and her breathing was heavy, the two sounds falling into rhythm as we walked between the

izbas

and onto the road cutting through the village.

Once there, we stopped and waited, the cold air biting at my legs.

‘Hello?’

My voice was dead and out of place.

‘Hello? It’s us. Nikolai and . . .’

I waited a while longer, watching, but nothing stirred, so I swung my leg over and dismounted. The sound was abrasive in the silence, and as soon as I was down, I stopped still, listening. I scanned the houses, wondering if anyone was watching me from the hush behind the closed doors. I glanced back at the forest, the trees black against the bruised sky, and thought perhaps I had been too eager to leave its protection. I had spent many days in there and now I felt exposed. But although it had hidden me well, the forest was a forbidding place that made it easy to believe in demons.

‘Hello?’ I called again, but still there was no answer. Doors and windows remained closed. ‘It’s Nikolai and Alek Levitsky.’ My voice was flat and without echo. ‘You can come out. We won’t harm you.’

With a deepening sense of unease, I drew my revolver and led Kashtan to my home, moving slowly. I hitched the reins round the fence and put a hand to her muzzle. ‘Stay here,’ I whispered, before forcing myself to look up at Alek. ‘I’ll come back for you in a minute,’ I told him. ‘We’re home now.’

The front door was closed but unbolted. It yielded to my first push, opening in to the gloom inside.

‘Marianna?’

The click of my boot heels was obtrusive on the wooden floor. I took a deep breath, expecting the smell of home, but instead there was something else. Not explicit, but a faint smell of decay that lingered in my nostrils.

‘Marianna?’

I had imagined the

pich

would be alight – the clay oven was the heart of our home, the place to cook, and the source of heat in winter. There would be bread baking in its furnace. Marianna would be smiling at Pavel, who would be playing with the little wooden figures my father had carved for me when I was a boy. Our eldest son, Misha, would be carrying logs in from outside. I had hoped for the warmth of a fire on an early winter evening, the faint lilt of a

garmoshka

being played in one of the other

izbas

.

But I found none of those things. No warmth. No life. Nothing.

The house was empty.

I stood for a long time in the half-darkness of my home. I called their names – Marianna’s and the boys’ – but no one came. The

pich

remained cold, and the house remained empty.

River water ran from me, dripping onto the floor, leaving a stain round my feet. The drips were the only sound and it felt for a moment as if this was another of my dreams. Perhaps I hadn’t reached home at all but was still beneath some grotesque tree in the forest, sheltering from the weather under its twisted branches, hiding from those who would see me dead. Or perhaps this was only a nightmare of what I thought I might find when I returned home.

But I knew it was real. The cold told me that. The

fear

told me that.

The weak sun of approaching winter had dropped by the time I forced myself to move, so that only a grey, grainy light slipped through the windows as I went to the

pich

and put a hand to it, feeling the coldness of the iron door, which lay open, and the hardened clay that surrounded it. In the depth of winter, we often slept above the oven, all four of us sharing the benefit of its heat, but now white ash slumped in a heap inside where it had burned itself out. Beside it, cooking implements leaned against the wall, ready to be used. Sprigs of dried plants hung from a narrow beam over my head, and one or two leaves had been pulled free and lain on the wooden surround. A neat pile of fresh logs and kindling was stacked in the corner.

On the table, four plates lay in no particular arrangement, as if they were about to be set out. The underlying smell in the room pointed to the presence of rotting food, but I saw nothing to indicate where the odour was coming from – nothing in the oven or on any of the plates – and the only food left in the cupboard was a handful of potatoes, some pickled cabbage and a few strips of dried pork.

In the centre of the table, a half-burned candle was glued with its own wax to a chipped bowl and I remembered how it was when the candle was aflame and voices filled the room. It was always warm and light, even in the deepest days of winter, when the

pich

was burning and my family was together.

As a soldier, I rarely had the opportunity to come home; my visits were sporadic and often came less than once a year. The last time I was inside this room was more than six months ago. It was early spring, and my unit was close, meeting with a larger force for resupply, so I took a week to visit home. Alek came too, and we sat at this table that first night and saw how Marianna and the boys coped with what little they had. Whites and Reds had been through the village more than once, taking what provisions they could find, leaving them with almost nothing, but I was thankful my wife and children had been left unharmed. Misha and Pavel were proud to show off the rabbits they had snared in the forest and the fish they had taken from the lake, just as Alek and I had snared and fished when we were younger.