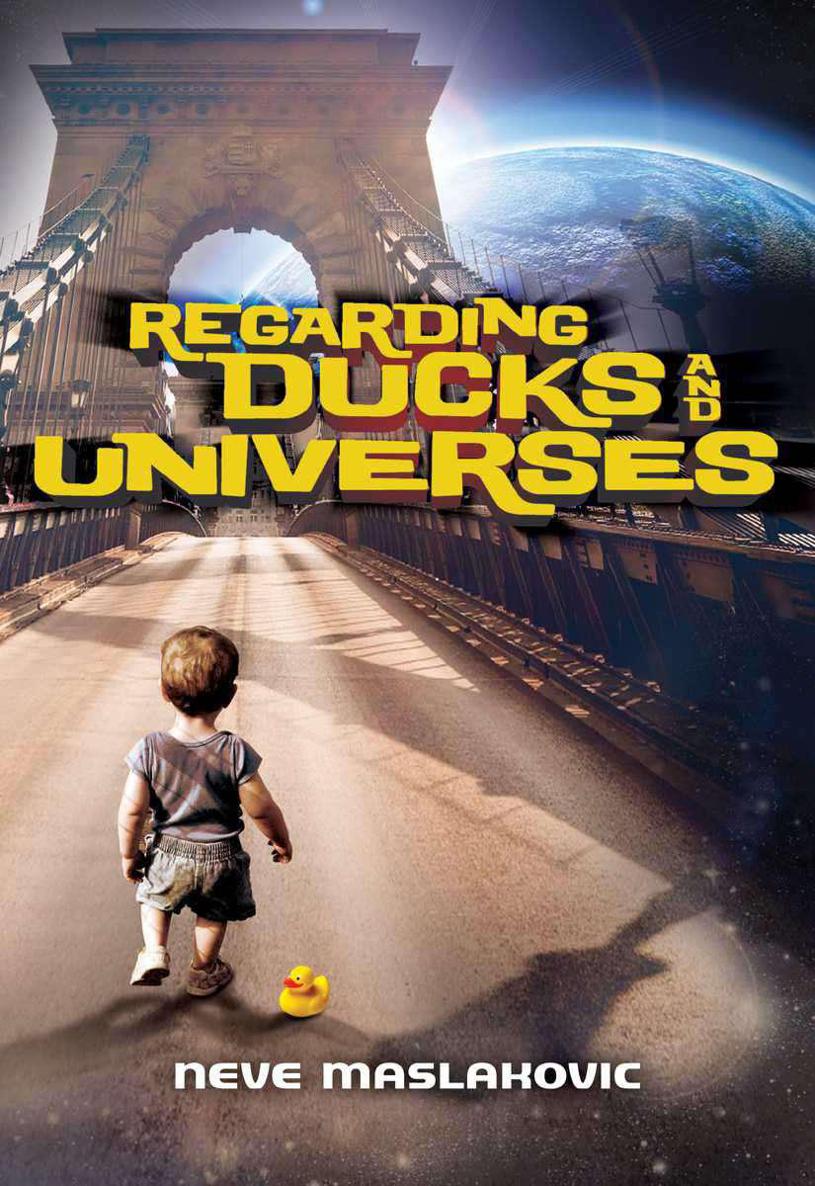

Regarding Ducks and Universes

Read Regarding Ducks and Universes Online

Authors: Neve Maslakovic

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Text copyright ©2010 Neve Maslakovic

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by AmazonEncore

P.O. Box 400818

Las Vegas, NV 89140

ISBN: 978-1-935597-34-6

For my father

HE

D

EPARTMENT OF

I

NFORMATION

M

ANAGEMENT’S

R

EGULATION

L

IST

Regulation 1: News & Media

Regulation 2: Places (maps, atlases, town & street names)

Regulation 3: Citizen Privacy

Regulation 4: Inter-universe Travel

Regulation 5: Intra-universe Travel

Regulation 6: Documents & Historical Records

Regulation 7: Alters

Regulation 8: Pet Ownership

Regulation 9: Identicard & Money Matters

Regulation 10: Office/Corporate

Regulation 11: Legislative

Regulation 12: Courts/Judicial

Regulation 13: Presidential Responsibility

Regulation 14: Naval/Maritime

Regulation 15: Technology

Regulation 16: Sport/Hobby

Regulation 17: Health & Medicine

Regulation 18: School/Educational

Regulation 19: Science & Research

Regulation 20: Arts

T

he DIM official had just asked, “Reason for crossing to San Francisco B, citizen—business, family visit, pleasure?”

It was none of them.

What had me in front of the DIM official’s booth, bag in hand, instead of at my desk at Wagner’s Kitchen contemplating the virtues of rice cookers and vegetable peelers, was this: Felix B. I needed to find out if he was less of a procrastinator than I was. Or if

his

job, whatever it would turn out to be, kept him less busy. And whether he required only six hours of night sleep rather than my usual nine, giving him plenty of free time to do with as he pleased. That sort of thing.

“I’m—just a tourist. Wanted to see what Universe B is like,” I said, nervously pushing my newly corrected identicard through the booth window.

The official reached up to take it, his avocado-green and turtlenecked uniform, standard issue for Department of Information Management employees, rising up in the back in the process. He glanced at the identicard but made no comment other than, “You look younger than thirty-five, Citizen Sayers. Just missed it, eh?”

“By a hair.”

As I waited while he typed something into his computer, a nearby ad, one of many that dotted the crossing terminal, caught my eye.

Sourdough bread—Warm. Tangy. BETTER in B

, it said; virtual baguettes tumbled from the old Golden Gate Bridge onto an ocean liner entering San Francisco Bay. Well, really, I thought. I’d heard that their sourdough bread was good, but

BUTTER

in B would have been catchier—not to mention more tactful. (Not that we A-dwellers didn’t have our share of ads bragging about pristine national parks, clean air, and the like, but none of them at Wagner’s Kitchen; Wagner made sure of that.) The virtual baguettes threatened to overflow the ship like a too-small breadbasket; then the ad changed and their place was taken by premium quality almost-cat food now available in both universes—

“Citizen Sayers?”

I turned my attention back to the booth. “Yes?”

“Regulation 7.”

“Right.”

“It prohibits you from seeking any information about your alter.”

“Right, right.” Even those of us who had grown up thinking they were uniques knew about Regulation 7.

“And from contacting your alter unless expressly invited to do so by Citizen Sayers B himself.”

“Right,” I repeated, swinging my backpack up across both shoulders. How Felix would know that I was in his universe to expressly invite me over for dinner or whatnot, the DIM official didn’t say, and I didn’t care. I had no intention of actually running into him, with or without an invitation.

The DIM official lifted a hand stamp, thwacked my ticket, and pushed it along with my identicard back through the booth window. I proceeded into the crossing chamber. A circle of seats had a glass ceiling above it and a luggage rack in the center. I put my bag on the luggage rack, found a seat near the door, and took a second look around. The Friday afternoon San Francisco–to–San Francisco crossing had attracted a mix of travelers, business types in suits and tourists in shorts and sandals. The more closely cropped hair on A-dwellers and the unwieldier-looking omnis around the necks of B-dwellers hinted at who was from which universe—the thirty-five years that had passed since Y-day had yielded the strangest differences. I leaned forward to get a better look at the luggage stacked in the middle of the chamber. There they were. Suitcases with two little wheels on the bottom and an inverted-U handle on the top. Someone had told me that we in Universe A used to have them, but the wheels and handles not being recyclable, they were gone. I rubbed my shoulders, sore from standing in line with my beige, biodegradable backpack. It was well known they were more relaxed about these things in Universe B.

Nothing in the chamber suggested that it was a vessel capable of ferrying us from one universe to the other. I had imagined heavy machinery and wires and flashing lights, not a sparsely filled round room with metallic walls and a skylight. For a moment I thought I saw a shimmer above the luggage rack, like a bit of warm summer air dancing over hot pavement, but decided I was imagining things.

“

Excuse me

,” a testy voice overrode the low music emanating from the seat speakers, “are we expecting more passengers?” The A-dweller (or B-dweller—she was one traveler about whom I couldn’t tell) seated on the other side of the luggage rack had lowered the magazine in her hands and addressed a crossing attendant walking by.

A wave of whispers swept through the chamber, like it was bad form to bother the attendants going in and out the narrow door. “We don’t give out traveler information, citizen. Regulation 4 concerning crossing procedures and privacy Regulation 3.” The attendant stepped out, then stuck his head back in. “And no calls in or out.”

She frowned, a slim omni in hand. “My companion is late.”

“It interferes with our equipment. Regulation 4.”

She let the omni fall back down around her neck, picked up the magazine again, and irritably started turning its pages. A couple sitting near me was very obviously sneaking glances in her direction and I twisted my head to see better around the luggage rack. A formfitting dress as orange as a carrot—no, a midwinter tangerine—drew attention to trendy ice-white hair and perfect skin. As I sat there trying to guess whether she was from A or B—she didn’t look old enough to have an alter, so it was possible she traveled freely and often enough to blur any distinctions—she looked up suddenly from the magazine, right at me. Something passed across her face. Caught staring, I quickly reached around my neck for something to read and she retreated behind the magazine again.

I had just began to browse mystery titles (nothing like a murder in a vicarage or a hound-haunted moor to keep one’s mind off the stresses of inter-universe travel) when someone asked, “Is this seat taken?” Face rosy and sweaty above her T-shirt, knitted hat askew, a large travel bag on one shoulder, the twenty-something B-dweller sat down with a thump into the empty seat on my left. “Whew, made it.” She pulled off the striped hat to reveal chestnut locks framing dark eyes and a round face.

I sat up a bit in my seat. After a moment or two while she settled in, I cleared my throat and said, “I’m looking forward to seeing what your universe is like.”

It was, I felt, a very courteous statement on my part. She didn’t hear me. She was looking up. I followed her glance but the only thing visible through the chamber skylight was the low-lying afternoon fog with a patch or two of blueness where the clouds had began to part. Feeling snubbed, I reached for the omni again, wiped a smudge off the screen, and went back to browsing the mystery section. As I scrolled down the list, I paused for a moment and imagined my name immediately below that of my namesake (no relation, this one) Dorothy Sayers, she of the eleven novels and twenty-some short stories starring the gentlemanly and monocled Lord Peter Wimsey. Or perhaps, I mused, switching to a different page, the mystery novel I’d write one day would be found in the New Arrivals section, where well-regarded and heavily advertised books usually began their journey into public awareness.

One is free to dream. Most likely anything I wrote would end up in the crowded Read for Free section.

“One hundred,” came a slow whisper from my left. “Ninety-nine…ninety-eight…ninety-seven…”

I glanced over to find our late arrival studying me and talking to herself under her breath. She closed her mouth and hastily looked away and I dabbed at my nose just in case there was something hanging off of it.

“I hate the waiting part,” she said after a moment. “So I try to distract myself with a countdown, like I’m in charge of the whole thing.”

“Does it work?”

“Not really. I think I know too much.”

“About—?”

“This.” She waved her hand around the small chamber. “Luckily I only have to cross once or twice a year, for work. It’s all we can afford.”

“Money,” I sighed. “Don’t we all have that problem.” I reached for the omni and the mystery list again, assuming that that was the end of the conversation; the Department of Information Management’s Regulation 3 all but prohibited people from sharing personal details, like names, with strangers. She continued speaking.

“I know there’s nothing to worry about. No one has been scrambled in a long time. Still…as I said, it’s just that I know too much.” Her stomach let out a low rumble. “Sorry. On my way to the crossing terminal I kept passing only restaurants that we have back home in Universe B. You know, the Lunch-Place Rule.” She unbuckled the large bag and started to rummage in it. “There should be a box of pretzels in here somewhere…I’m sure of it…”

“I’m sorry, the what rule?” I raised an eyebrow at her. Across the room, the A-dweller (or B-dweller) in the tangerine dress loudly snapped a magazine page into place, something that’s difficult to do on a product made of soft plastic, and sent another impatient look in the direction of the chamber door. Our eyes met again and this time there was no doubt—she seemed to know me.

“Did no one warn you about the Lunch-Place Rule?” A set of keys, a stick of gum, and a packet of tissues emerged from the bag, then disappeared back in. “About what would happen if walking around San Francisco B you came across your favorite lunch place—”

“Coconut Café,” I supplied. “Something about the spices. I can taste the food.”

“—that is, assuming your favorite lunch place exists and isn’t a parking lot or somebody’s lawn. So you go in and order whatever you like to eat—”

“Italian wedding soup. The Persian plate. The cheesecake of the day.”

“Soup, then. You taste the Universe B soup and perhaps find that it’s exactly the same as the soup in the Coconut Café of Universe A. Disappointing. After all, you’ve come all that way. Why can’t I ever find anything in here?” She closed the bag and dropped it on the floor where it landed with a soft thud. “Or the Universe B soup

isn’t

the same and you’re sitting there wolfing down a bowl of mouthwatering broth, knowing full well that the soup back home will never measure up again. Or”—she wrinkled her nose—“you’re sitting there horrified that your lovely lunch place has been replaced by a fast-food joint serving soup out of a can. There’s no way to win.” She glanced up again as the sun made a brief appearance, momentarily giving the metallic walls of the chamber a brighter sheen. “The Lunch-Place Rule applies to everything—buildings, waterfalls, even your favorite tree, if you have one.”

“Avoid everything familiar. I’ll keep that in mind. What’s up there?” I pointed.

“Any minute now the lid will slide into place.”

“The lid?”

“Same material as the walls.”

“And then?”

“We get swapped. It’s like this,” she went on before I could ask, an odd experience for me since I’m usually the one trying to keep the conversation going when it comes to women I’ve just met. She leaned across the elbow rest and continued, “Molecules stay, information travels. When the lid glides into place, the Singh vortex will activate and suck the information out of everything in the chamber, us, the chairs, the bags, like taking apart a house to see how it was built, then sending the blueprints elsewhere for it to be rebuilt—and building a new house in its place from the heap of materials left. After all, the human body is just an object, a shape, and yours is”—she looked over at me—” a medium-sized one, with light brown hair on top—”

I’d never realized I looked so ordinary.

“Really, blueprinting you is just a math problem. I’d need a couple of digits to describe the exact shade of your hair—more brown than light—a moderately long sequence for the shape and arrangement of your freckles, a

really

long sequence for what’s stored in your brain cells…It works something like that, only at the molecular level and in binary, zeros and ones. Your luggage gets turned into a sequence of its own. No chance of losing your bag.”

“Too bad—I wouldn’t mind returning home with one of those handy suitcases instead of my backpack,” I said, reeling from all the math. I had a sudden image of a conga line of zeros and ones, like Sherlock Holmes’s little dancing men, spiraling into the vortex that would hurl us into Universe B.

“At the other end—by the way, an equivalent amount of information has to get here, which is why crossings from A to B and B to A are synchronized—if they are a little short on one side they throw in the

Collected Works of Shakespeare

or a dictionary—where was I? Right. At the other end of the vortex you pop out in San Francisco B as you. Except, that is, for any interference errors, uncertainty principle ambiguities, or vortex anomalies.”

“Hold on.” I looked down at my body. “An approximation of me will arrive in San Francisco B?

And

I’m switching molecules with someone?” My voice had risen more than I’d meant it to. “When I head back, I’ll return as an approximation of an approximation?”

“You won’t notice any difference. Still, I always worry that a glitch will transpose a bit somewhere and I’ll step out of the crossing chamber bald. I think that’s why I always travel with a hat.” She dropped the knitted hat onto the bag next to her feet. I was self-consciously running my fingers through my hair, thinking how nice it would be if the bit for hair thickness accidentally flipped in my favor, when something cold touched my knee, bare below my khaki shorts, startling me.

“Murph, c’mon, we’re already late.” The lanky A-dweller who had just burst into the crossing chamber had a suitcase in one hand and a leash attached to a dog (an unusually pink-eyed and chubby dog) in the other. “Let’s put our suitcase on the rack. C’mon, Gabriella is waiting,” he urged as he scanned the room, presumably looking for said Gabriella.

“What kind of a pet are you?” the math woman inquired, reaching over to gently rub the creature’s head. Ignoring her as well as the tugging on its leash, the creature gave my knee another moist, scratchy lick.