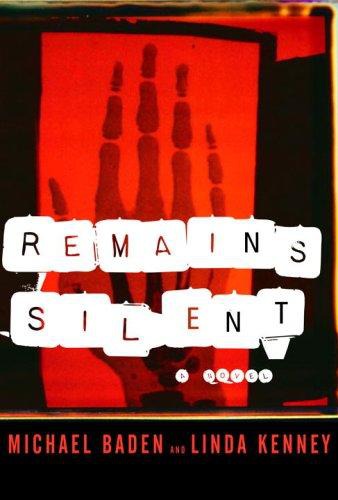

Remains Silent

A Novel

Michael Baden

&

Linda Kenney

ALFRED A . KNOPF NEW YORK 2005

LK: In memoriam to my father, Benjamin Benincasa, and to the real Filomena Manfreda, my mother, Faye Benincasa.

MB: To Eli and Ruby, our future.

No man chooses evil because it is evil;

he only mistakes it for happiness, the good he seeks.

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley

THERE WERE LOTS of things that drove her nuts: crowds, waiting in line, cheap shoes, lawyers without ethics but at the top of the list was being late for court. Manny

hated

it, absolutely hated it.

If she got to the courthouse looking like an escaped mental patient, as she sometimes did, she took time to pull herself together. No way shed appear before a judge unless she was the quintessence of cool. After a visit to the ladies room, her makeup would be flawless; every strand of flaming red hair would be in place. The line of her smooth stockings would lead to the very latest Vecchio stiletto heels; her documents would be in order, her arguments honed and ready for attack. At the very least, she would have earrings in both ears. She believed that an impeccable appearance bespeaks an orderly mind.

But timeliness and impeccable appearance might not be possible today. No, on this unexpectedly sweltering first Thursday in September, Manny was late and she was a mess.

It wasnt really her fault. Her sports car should have started even though shed left the vanity light on all night; an empty cab should have been available in front of her office, even though it was rush hour. Her fellow passengers herded onto the PATH commuter train should have given her room, even though there was not an extra inch of space and the man behind her seemed to enjoy pushing up against her butt. When without explanation the train stopped short of her station and sat in the tunnel for ten minutes, when she discovered she had somehow somewhere lost an earring, when the train finally lurched forward and the man stepped on her heel no wonder she was sweating, agitated, and thoroughly pissed off when she got to Newark. Not the best frame of mind for arguing a high-profile civil rights case before a jury and a federal judge, a case close to her heart, one she was determined to win.

Manny didnt like people to be treated unfairly; it was as simple as that. Her attitude started early. As a teenager, Manny and her best friend Leigh applied for summer jobs at a new doughnut shop on Main Street. Manny was hired. But Leigh, who was black, was not. Injustice! screamed Mannys soul. She vowed to fight, and fight she did. She organized a boycott of the shop, demonstrated in front of it with posters that accused the owners of racist hiring practices, and got the local television station to run a segment about it on the evening news. And she got a better job. Manny and Leigh were both hired as counselors at the local community center by the director, who was impressed by her activism.

Now, five years out of law school, Manny had earned a reputation as a tenacious fighter for the underdog. She had taken and won cases for the socially disadvantaged and disenfranchised, the kind of clients white-bread law firms considered beneath them. Lawyers wearing Brooks Brothers suits and club ties didnt relate well to clients in baggy jeans with tattoos and body piercing, though she even in Dolce & Gabbana and Versace had the knack. Besides, Mannys clients couldnt afford to pay $600 an hour. Often they paid little or nothing. If she won their cases, she took a percentage of the awards.

Manny was prepared to raise hell again, this time at the wrongful-death trial of Esmeralda Carramia. As she waited to go through the metal detectors, she regained her composure, for she had enough time to freshen up before court resumed less than ten minutes, but enough. She was ready. She knew the case inside and out, having memorized the facts so thoroughly she might as well have been at the crime scene herself. The events central to the Carramia case had unfolded in a matter of minutes, but it was enough time to leave a family heartbroken, a city torn apart, and a police force accused of racism and brutality.

* * *

Newark, New Jersey, November 25, 2003. Esmeralda Carramia walks into Steinless, the last department store left downtown. She needs a birthday present for her grandmother. Esmeralda, her grandmothers adored Essie, is the daughter of emigrants from the Dominican Republic who have just moved from Miami to Newark. The store clerk, who is white, pointedly ignores her. Then she accuses Essie of shoplifting a $49 silk scarf. Essie denies it. Voices are raised. Security is called. Essie gets agitated. She is told to calm down. She does not. The police arrive within minutes. Essies tote bag is searched; a scarf is found, price tag dangling. She says the clerk planted it there, swears it on the Virgin of Guadalupe. No one believes her. The police take her outside, try to arrest her. Essie resists. She lashes out. Her parents will testify this is completely out of character. In the melee, one officer takes a knee to the groin; anothers nose is bloodied. Backup arrives. By now there are six policemen on the sidewalk, none weighing less than 160 pounds. Essie, at 5 feet 2 inches, weighs 105.

Later, no one can say who was responsible when her head struck the pavement. As the police put her in the squad car, they realize she is unconscious. At the hospital, Esmeralda Carramia is declared brain dead. She is nineteen years old.

Injustice!

Manny had taken the case two months later, when Esmeraldas parents arrived in her office armed with childhood pictures and righteous indignation. They had come to America for a better life, they said, and the people sworn to protect Essie had murdered her instead. Here was a picture of Essie dressed in white for her first communion, and in a white frilly gown for her

quinceanera.

And if Manny needed further convincing, here on their lap was little Amaryllis their one-year-old granddaughter, Essies daughter destined to grow up without a mother.

Though no amount of money would bring their daughter back, they wanted the people who killed her to pay.

Manny had jumped into the case with her usual zeal. She had deposed the cops, the witnesses, and the store employees. There was no question as to the facts: Esmeralda had struggled, fallen, and died. Her forensic pathologist had agreed with the state medical examiner on the cause of Essies death: a blow to the head resulting in a subdural hemorrhage.

Essies parents and grandmother had been simple and eloquent in their testimony. Their Essie was a good girl, religious, never done anything wrong before, let alone stealing. Manny had rested her case, knowing the jurys sympathy was with her clients. Let opposing counsel try to justify the cops actions. She would use whatever they said to rip them apart in her closing argument.

* * *

When Manny went through the metal detectors, an alarm beeped. The federal marshal waved a wand down the length of her body, stopping at her shoes: Italian designer black-on-black fabric-embroidered dOrsay pumps. You gotta stop wearing these, Ms. M, he said. Ive told you a thousand times, theres metal in the heels.

Just testing you, Manny said flirtatiously. Besides, they go with my outfit. She walked across the green-and-white marble floor of the courthouses imposing rotunda and headed upstairs to the ladies room.

Manny fixed her makeup, put her hair up in a twist, and smoothed the jacket and skirt of her electric-blue suit with the leopard-skin lining. The suit brought out the color of her steel blue eyes, and the matching V-necked silk blouse offered a little something to keep the male jurors happy. Not too bad, she thought, assessing herself in the mirror. I can pass off the one-earring look as a fashion statement.

At twenty-nine, she knew that some of her colleagues thought she wore killer shoes and bright colors to make herself stand out but that wasnt totally accurate. Her clothes were a kind of armor, a talisman. They declared she was someone who made bold decisions and was confident and comfortable with herself. Your clothes not only represent who you are, they also say what you

want

to be. When she became a trial lawyer, the philosophy served her well. She knew instinctively that juries would be more inclined to believe a well-dressed, smartly accessorized lawyer than a woman trying to look like a man in a bow tie, boring low-heeled black shoes, and a shapeless suit. Her parents had taught her to buy the best clothing she could afford, even if it meant eating bean soup for dinner. Even now there was soup many nights, but she ate it, if alone, in a Ralph Lauren bathrobe. Her family was proud of her. And she liked to shop, especially sales. It was her primary hobby.

She examined herself in the mirror one last time, aware of her flaws owing to her healthy appetite for food and wine and her 5-feet-8-inch height, she wore a size eight rather than the four she fantasized; also, there was a little bump at the edge of her nose, a genetic inheritance from her father she hadnt had the nerve to fix with plastic surgery but reasonably satisfied. Her cheekbones were good she got

those

from her mother and the fire in her eyes, the joy of battle, was hers alone.

A stranger in the courtroom might assume she was someones client another society wife a lady who lunched. An opposing lawyer might treat her as a bimbo who was sleeping with one of the senior partners until she presented her case, that is.

Manny had remembered to pin a small square of red cloth inside her suit jacket for luck, something her grandmother had taught her to do, just in case. She was taking no chances; no one would cast an evil eye on her, not today. She needed to win.

She entered the courtroom a striking space with red velour jurors chairs and blue carpet and took her place at the massive oak plaintiffs table. Two minutes later, the court was in session.

* * *

The defense calls Dr. Jacob Rosen.

Jake Rosen. Maybe he was why she felt edgy. She had met him last March, when she needed a second autopsy in the Jose Terrell shooting and had arranged to helicopter him to a New Jersey field next to the morgue actually paid out of her own pocket! so he could confirm the bullets that killed Terrell were fired by the cops while Terrell had his hands up in surrender.

Rosen had bounded out of the copter like a fashion-challenged Frankenstein with the unkempt hair of a mad scientist. The hair was long and thick, brown peppered with a few strands of gray; shed had a ridiculous impulse to comb it for him just to feel it under her fingers. He carried a folded raincoat on top of a weatherbeaten black briefcase so full of papers he couldnt fasten the clasp, but he was superbly professional; his findings were so thorough the detective who fired the fatal shots struck a plea bargain, the city paid damages to the boys mother, and the case never came to trial.

Now here was Rosen again, six months later, testifying for the defense. Manny knew that private experts could work for anyone they wanted, but she still felt betrayed. Hed been so patient with her, so cooperative. She felt hed been as outraged as she was by the first, obviously bogus, coroners report in the Terrell case. He seemed to care about truth then; now she knew his testimony could be sold to the highest bidder.

Manny barely looked up when he came in. She knew what he was going to say, but her own forensic expert had assured her that his opinion was a load of crap. So what if shed briefly momentarily thought him attractive? He was Judas incarnate.

Today as he walked to the witness chair he looked like nothing more than some high-priced egghead from central casting trotted out by the cops to rationalize their bad behavior. Manny knew he was only forty-four, but under the courtroom lights he looked older. And he needed to go to a Pilates perfect-posture class to cure his slouching shoulders. He was wearing a black suit, a white shirt, and a skinny black tie. If he had spiky hair instead of the mad-scientist kind hed have looked like an aging eighties British punk rocker. In the months since shed seen him hed grown a mustache. Facial hair from the seventies, clothes from the eighties What was his problem? Hadnt anyone told him he was living in the twenty-first century?