Resolute (23 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

HOWEVER, THE AMERICANS

, and especially Elisha Kane, were far from ready to give up. Kane had arrived back in the United States on September 7, 1851, to great acclaim, not because of anything he had done in particular but because of his writing skills. He had not made the discoveries at Beechey Islandâthat had been accomplished by Penny's menâbut he had, in his own unique writing style, been the first to report the significant find. On September 24, 1851, six days before the

Advance

docked back in New York, both the

New York Daily Times

and the

New York Daily Tribune

ran articles Kane had written about what had been foundâlong before the first accounts of the discoveries had reached the English newspapers. Not by deed, but by association, Elisha Kane became a hero. He was quick to capitalize upon it. Immediately he began writing other articles and giving spirited lectures. At the same time, he wrote a long narrative titled

The U.S. Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin

, which became a huge success. Fortunately he had the field to himself. De Haven, the actual commander of the expedition, had little writing skill and even less inclination to seek publicity.

Kane could not have been more delighted with the spotlight that was now cast upon him. For he had a not-so-hidden goal. He was angling for his own expedition to search for Franklin. “I must seize the present occasion,” he exclaimed in one of his many speeches, “to state that I hope the search is not yet ended. The drift by which the

Advance

and the

Rescue

were borne so far, conclusively proves that the same influence might have carried us into the same sea in which Franklin and many his companions are probably immuredâ¦I trust for the sake of the United States, for the sake of the noble-hearted woman who has been the animating soul of all the Expedition, for the sake of this flag which has so triumphantly borne the battle and the breeze, for the sake of the humanity that makes us all kin, I trust that [the] search is not yet ended, and the rescue of Sir John Franklin is yet reserved to this nation and the world.”

Finding that his lectures were increasingly well received, Kane stepped up the pressure. He not only wanted the search to continue; he had a strong notion of where Franklin was to found. Like John Barrow years before him, Kane had become a firm believer in the existence of an Open Polar Sea. As the number of his speeches increased, so too did his emphasis on his conviction that Franklin and many of his men were still alive and were trapped in this sea, “unable to leave their hunting ground and cross the frozen Sahara which has intervened between them and the world from which they are shut out.”

Typical of the expert persuader that Kane had become, he covered all his bases by publishing an article in the

Daily Pennsylvanian

stating that even if Franklin were no longer alive, it was imperative for the sake of humanity that the search be continued, and as soon as possible. “Sir Franklin has now been absent about six years and eight months,” he wrote. “More than a year beyond the longest period for which his provisions could hold out, according to the most favorable estimate of his friendsâ¦We are afraid that there is in prosecuting the search, but little hope for more than to put an end to uncertainty by bringing the fact and manner of their loss. Even for this purpose, however, with the remote probability of finding the adventurers sill alive, it is a high duty to humanity to persevere and hope to seeâ¦an early renewal of the search put into execution.”

Once again, Henry Grinnell answered the call, this time with added support from American financier George Peabody, the United States Department of the Navy, and various scientific organizations. Kane would get his wish. He would be given a ship. Once again it would be the

Advance.

And this time, he would be in command.

On May 31, 1853, with a huge crowd of well-wishers cheering them on, the seventeen officers and men of the

Advance

left New York Harbor ready to fulfill their “high duty to humanity.” It was a most unusual crew. As one Arctic historian would write, “Its captain was a physician in poor health, his chief officer a boatswainâ¦and his principal navigator a landsman astronomer.” But before the expedition was over, newspapers would call it “the ultimate romantic adventure.”

Kane's goal was to sail to Baffin Bay and then proceed north to the shores of the Polar Sea. By July 20, he had reached Greenland and had put into the whaling port of Upernavik, where he enlisted the services of Johan Carl Christian Petersen, a Danish sledge driver and interpreter. He then made his way through Baffin Bay and, with ice building all around him, attempted to cross Smith Sound. He made it, but only after the crew had dragged the

Advance

through the ice much of the way. In early September he was completely icebound in Rensselaer Harbor.

It was to be a horrendous winter. Temperatures would drop to as low as seventy degrees below zero. Fifty-seven of the sixty dogs that Kane had purchased in Greenland for sledging purposes would die. Everyone aboard would, to one degree or another, feel the effects of both scurvy and malnutrition. The only positive note in the long, dark winter was Kane's good fortune in being able to hire the nineteen-year-old Inuit Hans Christian Hendrik, who would prove invaluable to him.

When spring arrived and it became obvious that the ice was still a long way from breaking up, Kane decided to send out sledge parties to search the area. Surely, there must be some signs that Franklin had passed this way. They found not a trace, but their long explorations brought other results. Boatman William Godfrey and ship surgeon Dr. Isaac Hayes were able to map a large area of what became known as Kane Basin. Kane himself made two significant discoveriesâan enormous ancient ice mass that he named Humboldt Glacier and a unique rock formation that he named Tennyson's Monument. To Kane, however, these discoveries paled in comparison to what Hans Hendrik and ship's steward William Morton had found. Late in July they had pushed on past Humboldt Glacier and eventually reached a spot from which they spied open water. When they reported back to Kane, he could hardly contain himself. There

was

an Open Polar Sea, and along its shores maybeâjust maybeâthere was Franklin. He had to see it for himself. But even though it was now summer, conditions were becoming impossible. Ice formations blocked his way, and he and the other sledge parties were forced to return to the ship.

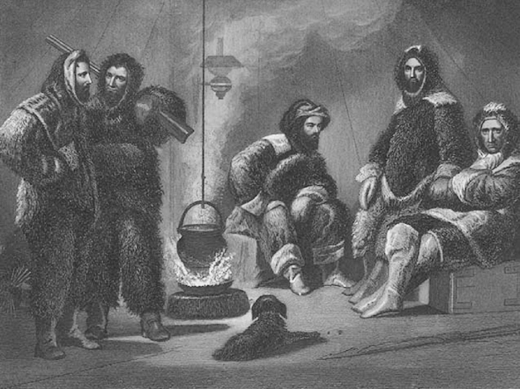

ELISHA KENT KANE'S

second northern expedition was one of the most harrowing of all Arctic ventures. Here, in an illustration from Kane's bestselling book, the explorer (center) and his officers pose for the expedition's artist while spending yet another winter day trapped in the brig.

By mid-July, with the ice that surrounded the

Advance

for miles as thick as it had been when they had first become imprisoned, it became clear to all aboard that there would be no escape for at least another year. With several of his crew becoming increasingly desperate and difficult to manage, Kane decided upon a desperate measure of his own. Aware that Edward Belcher's fleet had its base of operations at Beechey Island, he took five of his men and, in a small boat, set out for help. But it was a futile attempt. Every passageway was blocked and they had no choice but to turn back.

Then, in early August, a group of the crewmen suddenly came to Kane with a decision they had made. They were convinced, they stated, that the only chance for survival was to leave the ship and attempt to gain rescue by journeying on foot to Upernavik. Kane was shocked. It was more than a thousand miles to Upernavik and they were still in the season of ice and blizzards. They would never make it.

After pleading with the crew members to reconsider and detailing why he felt that it was far safer to stay with the ship, Kane told them that their decision should be put to a vote. Confident that they would take his advice, he added that those who did decide to leave would be given whatever provisions could be spared and would be granted immunity from desertion. To his complete shock, nine of the crew, including Dr. Hayes, voted to go.

They left on August 28. In his journal, a distressed Kane, battling to keep his usually good nature intact, wrote, “So they goâ¦I cannot but feel that some of them will return broken down and suffering to seek a refuge aboard. They shall find it to the halving of our last chipâbutâbutâbutâif I ever live to get homeâhome! And should I meet

Dr. Hayes

or [the others]âlet them look out for their skins.”

His words were prophetic. In mid-December all of those who had departed returned. In their flight to safety, they had nearly died. Several had been injured. Hayes's foot had been mutilated. All were on the verge of starvation. With as much good grace as he could muster, Kane took them back aboard and shared with them the

Advance's

supplies, which were now dangerously low.

By May 1855, the provisions were almost gone. How ironic it was, thought Kane, that the only possible, yet unlikely, way out he could think of was to follow the same plan that the “deserters” had tried to pursue. On May 20 the ship was abandoned. For the next eighty-three days, the men of the

Advance

, carrying invalid members of the crew with them, traveled over thirteen hundred miles on foot and by boat. Finally, in August, they were spotted and taken aboard a Danish whaling vessel headed for Disko Island, some 250 miles south of Upernavik. One of the men died. Kane was near death himself. But they had managed their incredible escape.

BACK HOME

, they had not been forgotten. In April, a month before the

Advance

had been abandoned, two United States naval vessels commanded by Captain Henry J. Hartstene had set sail in search of Kane. Informed by telegraph that Kane and his party were at Disko Island, Hartstene arrived there on September 13. Kane would later describe his first meeting with the captain as he and his men were being ferried from the island to Hartstene's ship. “An officer whom I shall ever remember as a cherished friend, Captain Hartstene, hailed a little man in a ragged flannel shirt, âIs that Doctor Kane?'âand with the âyes' that followed, the rigging was manned by our countrymen, and cheers welcomed us back to the social world of love which they represented.”

Elisha Kane returned to New York on October 11, 1855. The lecture tours, speeches, and writings that would follow would make him even more famous than ever. He had not found Franklin, nor had he set foot in the Open Polar Sea. But unbeknownst to him, the route that he had followed and charted would provide the avenue for explorers to come and the eventual discovery of the North Pole.

CHAPTER 12.

CHAPTER 12.The Resolute Comes Home

“I don't know how I did it.”

â

CAPTAIN JAMES BUDDINGTON

, 1855

C

APTAIN JAMES BUDDINGTON

simply could not believe what he was hearing. His four crew members had finally been able to return to the

George Henry

after spending three days aboard the ship that the whalemen had come upon in Davis Strait. Now they were not only telling him that they had found absolutely no one on board the other vessel but that they had discovered that the giant “ghost ship” was a British naval vessel named HMS

Resolute.

Buddington was stunned. The

Resolute?

Wasn't that one of the ships that had been sent out in search of John Franklin? Wasn't that one of the same vessels that, according to the stories he had heard from other whaling captains, had been callously abandoned by that British commander who had been court-martialed for doing so? But that ship had been left in the ice some twelve hundred miles away. It couldn't be. How could she possibly have made her own way across the Arctic to where she now stood across from him, completely on her own?

His men must be mistaken; but he had to see for himself. Taking a small party with him, he crossed the ice to the mystery ship and boarded her. He hadn't believed his ears when his men had given him his report. Now he couldn't believe his eyes. There was the nameplate, rusted but clearly legible. There were the barrels marked

Resolute.

There were the life jackets bearing the same name. “My Lord,” exclaimed Buddington to the Arctic air, “it is the

Resolute.”