Resolute (33 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

Finally, on March 4, 1880, they reached the bivouac at Camp Daly, only to find that Captain Barry was nowhere in sight. “We had Captain Barry's word that he would await our return,” Schwatka wrote. “But upon arriving at Camp Daly ⦠the greater part of the party's provisions, trading material, and other stores placed in Captain Barry's charge had disappeared with him.” Totally disgusted with Barry, Schwatka led his party to Marble Island, where they were able to book passage on the whaleship

George and Mary

, which brought them safely to its home port of New Bedford.

Schwatka's safe return was hailed throughout America, especially by Isaac Hayes who, at a reception honoring the explorer's achievements, stated, “Lieutenant Schwatka has performed a journey unparalleled in the history of Arctic travels. It was a bold undertaking ⦠yet, by persistently following a fixed plan of operations, by never once faltering in the direct purpose of his journey, and above all by the proper exercise of a natural gift of commandâ¦he has won a splendid victory and added his own to a long list of illustrious names connected with this Arctic searchânames which the world will not willingly let die.”

Six months later, the London

Times

presented its assessment of Schwatka's accomplishment. “The importance of the results achieved by Lieutenant Schwatka's expedition has not been gainsaid by any one possessing the least acquaintance with Arctic matters. It made the largest sledge journey on record, having been from its base of supplies for eleven months and twenty days, and having traversed 2,819 geographical, or 3,251 statute miles. It was the first expedition that relied for its own subsistence and for the subsistence of its dogs on the game that it found in the locality. It was the first expedition in which the white men of the party voluntarily assumed the same diet as the natives. It was the first expedition that established beyond a doubt the loss of the Franklin records. McClintock recorded an opinion that they had perished; Schwatka recorded it as a fact.”

CHAPTER 17.

CHAPTER 17.Remarkable Gift, Enduring Mystery

“Man has always gone where he has been able to go.

It's simple. He will continue pushing back his frontier,

No matter how far it may carry him from his homeland.”

â

Apollo 11

astronaut

MICHAEL COLLINS

, 1969

W

HEN HE HAD OFFICIALLY

turned the

Resolute

back over to Great Britain, Captain Henry Hartstene had expressed the hope that “long after every timber in her sturdy frame shall have perished, the remembrance of the old

Resolute

will be cherished.” He had no idea of how dramatically his hope would be realized.

On the morning of November 2, 1880, in a time when security was minimal and the Secret Service did not exist, an express wagon hauling an enormous crate pulled up to the delivery entrance of the White House. As William King Rogers, private secretary to President Rutherford B. Hayes, signed for the crate, he tried to imagine what could possibly be inside. No packages were expected at the presidential mansion that day, certainly nothing as massive as this one. What could it possibly be?

Totally bewildered, Rogers asked the president to join him, and the two men looked on as workmen pried open the mysterious package. Their bewilderment turned to amazement when they saw what the crate contained. It was the most magnificent desk either man had ever seen, beautifully carved, four feet deep and six feet wide. It had to weigh at least thirteen hundred pounds. Where could it have come from? Who could have possibly sent it?

They got their answer when they noticed the brass plaque attached to the front of the desk. It read:

H.M.S.

“Resolute”âforming part of the expedition sent in search of Sir John Franklin in 1852, was abandoned in Latitude 74°41'N, Longitude 101

°22'W

on 15th May, 1854. She was discovered and extricated in September 1855 in Latitude 67°N by Captain Buddington of the United States Whaler “George Henry.” The ship was purchased, fitted out and sent to England as a gift to her Majesty Queen Victoria by the President and people of the United States as a token of goodwill and friendship. This table was make from her timbers when she was broken up, and is presented by the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, to the President of the United States, as a memorial of the courtesy and loving kindness which dictated the offer of the gift of the “Resolute.”

President Hayes was delighted. He had read about the

Resolute's

heroic accomplishments during the Franklin search. He knew how the ship had been miraculously saved and then restored and given back to England. He had been disturbed to discover that, for whatever reason, the vessel had not been put back in service. But now, thanks to the generosity of Queen Victoria, the

Resolute

, in a much different form, was alive again. Immediately, the president ordered that the desk be installed in his office on the second floor of the White House.

Since Hayes, every chief executive of the United States except Presidents Johnson, Nixon, and Ford, has used the desk. Some of the nation's most important pieces of legislation have been signed upon it; many of the most memorable presidential speeches and announcements have been made from behind it.

In 1952, the

Resolute

desk was moved to the Broadcast Room on the White House's ground floor, where it was used by President Dwight D. Eisenhower for his radio and television addresses. In 1961, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, aware of her husband's love of the sea and its history, had the desk placed in the Oval Office. There it became the setting for the famous photograph of the young John F. Kennedy, Jr., peering out from behind its open kneehole panel. From 1966 to 1977, the desk was the centerpiece of an exhibition held at the Smithsonian Institution. In January 1993, President William J. Clinton had the desk returned to the Oval Office, where it remains today.

The

Resolute

desk has twice been modified. President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked that the kneehole be fitted with a panel carved with the presidential coat of arms, but did not live to see it installed in 1945. President Ronald Reagan had a two-inch base placed beneath the desk to accommodate his six-foot-two frame.

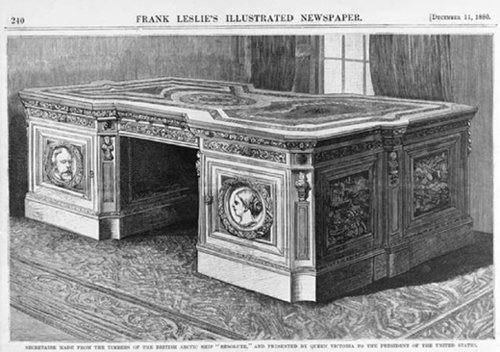

THE DECEMBER 11

, 1880 issue of

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper

featured this illustration of the

Resolute

desk. The accompanying story heaped praise on the beauty of the desk and emphasized how Queen Victoria's generous gift was a major step in cementing British-American relations, a process that had begun with the restoration and return of the

Resolute.

Although President Hayes had had no way of knowing it when he received the treasured gift, Queen Victoria had actually ordered that two other smaller desks be made from the

Resolute's

timbers. One was gratefully presented to Lady Jane Franklin. The other was given to Mrs. Henry Grinnell, the widow of the man whom Charles Dickens described as having “spent a large part of his fortune in the search for [Franklin's] lost ships, when none knew where to look for them.”

The brass plaque on the desk given to Mrs. Grinnell contains words similar to those on the desk residing in the Oval office, but concludes: “This tableâ¦is presented by the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland to Mrs. Grinnell as a memorial of the disinterested kindness and great exertions of her late husband Mr. Henry Grinnell in assisting in the search to ascertain the fate of Captain Sir John Franklin, who perished in the Arctic regions.” Enhancing this desk, which now resides in the New Bedford Whaling Museum, are two ceramic figurines, one of Sir John Franklin, the other of Lady Jane, the woman who never stopped looking for him. As one publication stated, it is a desk that “symbolizes the links of sympathy not only between the nations but also between two widows, one a New York City matron, one the Queen of Great Britain.”

The

Resolute

desks are not the only permanent reminders of the ship that made what has been called “the most miraculous voyage in history.” The collections of the Vancouver Maritime Museum contain the

Resolute's

bulkhead clock engraved with the name “H.M.

Barque Resolute”

and signed by its manufacturer, the English clock-maker Edward Dent, best known as the creator of London's fabled “Big Ben.” The museum's collections also include a unique treasure: the playing cards used by the crew of the

Resolute

, discovered by the men of the

George Henry

when they first boarded the vessel. Made to withstand the long, damp Arctic winters, they were fashioned from the tin cans used to preserve the food brought from home. Other known

Resolute

artifacts include the ship's spyglass and sextant, housed in the New London County Historical Society, and its bell, presented in 1965 to President Lyndon B. Johnson by British prime minister Harold Wilson.

THE FASHIONING OF

the desks signaled the final chapter in the story of the

Resolute.

There would be no mystery attached to what happened to the ship destined to play such an integral role in the Franklin saga. The same could not be said of the 128 men that she had tried so desperately to find. M'Clintock's and Hobson's discoveries had done much to begin the unraveling of the mystery. The Inuit testimony gathered by Hall and Schwatka filled in important pieces of the puzzle. But major questions remained. Where exactly had Franklin steered the

Erebus

and the

Terror

before he and his men had met their fate? Most important, what had really happened to them? How could such an unprecedented human tragedy have taken place? How exactly had they died?

Given Sir John's determination to complete his mission, it is most likely that he would have tried to cover as much distance as possible before winter set in. And, in fact, we know that both he and John Barrow fully expected that he would find the passage and sail through it in a single season. That might explain why initially he did not interrupt his voyage to stop and build cairns containing news of his progress.

It can be assumed that, as his orders dictated, he steamed through Lancaster Sound and then moved on through Barrow Strait. Ahead of him would have been Cape Walker, the last spot of land on his map. Looking to the southwest, he would have seen the unexplored territory that he had been told to investigate. But, in all probability, he found that ice barred his way in that direction. His orders mandated that if he was unable to proceed southwest, he was to turn north through Wellington Channel, which, knowing the man and his strict devotion to following orders, he would have done.

As Franklin headed north through the unknown territory surrounding Wellington Channel he would eventually have encountered the then-uncharted Grinnell Peninsula, which would have turned him to the northwest. By this time, ice would have been building up in the area, and eventually his way would have been completely blocked. He would have been forced to retreat to Barrow Strait but would have found his way to the west also blocked. Most Arctic experts agree that what probably happened next is that Franklin then found a passageway that he was confident would take him close to King William Land (he would not have known that John Rae and others had discovered it was an island). This must have truly excited him, for what we know for certain is that, based on his own previous Arctic explorations and those of othersâparticularly Simpson and Backâhe truly believed that from there, it was clear sailing to open western waters. Later, colleagues back home would remember how before setting sail, Sir John had placed his finger on that area of the map, declaring, “If I can get down there my work is done; thence it's plain sailing to the westward.”