Resolute (9 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

From Lancaster Sound, Parry sailed on to Prince Regent Inlet, hoping that that waterway was the next link to the passage. But he found it blocked by ice. His two ships, the

Hecla

and the

Griper

, then pushed on, entered Barrow Strait, and explored the south shore of a previously unknown group of islands that Parry named the North Georgian Islands. The vessels had now reached the Arctic Archipelago, the first European ships ever to do so. On September 4, they were off the south shore of Melville Island when Parry's instruments told him that they were crossing latitude 110 degrees west. They had earned the five-thousand pound prize that Parliament had offered for reaching this point.

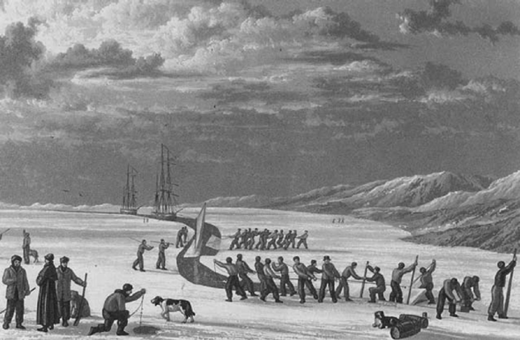

EDWARD PARRY

was the first of the British naval officers to deliberately spend the winter in the ice so that his search for the passage could be extended a second season. Here, with the ice beginning to thaw, the crews of the

Hecla

and the

Griper

undertake the arduous task of cutting a channel to free the vessels from their entrapment.

Aware that winter was pressing in on him, Parry tried to keep moving west but his path was increasingly being blocked by building ice. Rather than risk disaster, he decided to put into what he named Winter Harbor on Melville Island. He had planned well. He was fully prepared to become the first to voluntarily “winter down” in the Arctic and wait for the ice thaw before resuming his journey.

Parry knew it would be a long and challenging winter. But his spirits had never been higher. He had confirmed that there were no Crocker Mountains blocking Lancaster Sound. He had claimed the first of Parliament's rewards. And even better things, he believed, lay ahead. “Our prospects, indeed, were truly exhilarating,” he wrote in his journal. “The ships had suffered no injury; we had plenty of provisions, the crew in high health and spirits; a sea, if not open at least navigable; and a zealous and unanimous determination in both officers and men to accomplish, by all possible means, the grand object on which we had the happiness to be employed.”

But first they would have to get through the winter. He knew that the greatest challengeâgreater even than the ice or snowâwould be boredom. “I dreaded,” he stated, “the want of employment as one of the worst evils that was likely to befall us.” Long before he had left for the Arctic, Parry had carefully planned for a work regimen and an ongoing array of entertainments to keep everyone occupied should they have to spend the winter in the ice. Every day, from 5:45

A.M.

until nightfall, the men on both ships were kept busy with activities ranging from scrubbing the decks to mending and checking the rigging and sails. Anticipating the need for evening entertainment, Parry had brought with him costumes, makeup, and scriptsâeven a barrel organ, so that classic and comic productions and musicals could be presented. A weekly newspaper,

The North Georgia Gazette and Winter Chronicle

was published. Cricket and other games were held on the ice that surrounded the vessels. Although he had no way of knowing it, Parry had instituted a program for dealing with spirit-killing boredom that, in years to come, would be employed time and again by winterbound Arctic ships.

The

Hecla

and the

Griper

remained in their frozen entrapment for almost a full year. It was not until the first of August that the ice finally began to break up and the ships could get underway. But as Parry resumed sailing westward he discovered that the waters ahead of him were still clogged with ice. Miles off in the distance he could see land, which he named Banks Land, but he knew he would never be able to reach it in that season. It was time to go home.

The passage had not been found, but Parry had accomplished more than any other seeker had ever achieved. He had proven that Lancaster Sound opened a passage to the west. He had verified the need to map the maze of islands through which any successful passage-seeker would have to travel, and he had demonstrated that wintering in the Arctic without disaster was possible.

Immediately upon returning, Parry was promoted to the rank of commander. He was elected unanimously as a fellow of the Royal Society and was publicly honored by various institutions and hailed wherever he went. Most important to his future prospects, he had justified the faith that Barrow and the Admiralty had placed in him. “No one,” Barrow would write after reading Parry's report, “could rise from its perusal without the fullest conviction that Commander Parry's merits as an officer and scientific navigator are not confined to his professional duties; but that the resources of his mind are equal to the most arduous situations, and fertile in expedient under every circumstance, however difficult, dangerous, or unexpected.”

High praise indeed. And in six months Barrow had sent his hero off again. Parry could not wait to return. “How I long to be among the ice,” he had told his friends. Once again he was given two ships. He would command the 375-ton

Fury.

Command of his old ship, the

Hecla

, was given to George Francis Lyon, who had become a favorite of Barrow's by overcoming extreme hardships during an expedition that Barrow had sent to Africa to trace the course of the River Niger.

This time, instead of pursuing the path through Lancaster Sound, Parry had been instructed to sail westward through Hudson Strait toward Repulse Bay. Again, any scientific observations he might make were secondary. He was to finish the job; he was to find the passage.

The

Fury

and the

Hecla

set sail on May 8, 1821, and by the end of July had entered Repulse Bay. But Parry soon found that, even this early in the season, his progress westward was blocked by ice. Turning from the bay, he and Lyon spent the next two months following the coast of Melville Peninsula, exploring every inlet, anxiously searching for a passage to the west. By October, ice was forming everywhere and the two ships were forced to put into a sheltered spot that Parry named Winter Island. There, for the next nine months, they would be frozen in position.

Immediately, masts and sails were stored and the work and entertainment regimen was begun. Parry, now a veteran of “wintering over,” had added new features to occupy his men. Along with regular performances by the Royal Arctic Theater, now equipped with stage lights, Parry introduced a school aboard each of the vessels where crew members were taught both reading and writing. An observatory was built onshore where men of the

Fury

and

Hecla

took magnetic measurements and made other scientific observations.

Much of the inevitable boredom of the long winter was relieved by something for which Parry could not have planned. On February 1, 1822, a group of Inuit suddenly arrived and informed Parry that they had built a winter settlement just two miles away. For the next several months the Eskimos paid regular visits to the ships. Most important, they spoke of a strait that lay to the north of Winter Island, a passageway that provided access to open water to the west. Now the monotony of the wintering over was replaced by impatience. Could this passageway lead to success at last?

Impatient as he was, Parry was forced to wait until the first week of July before the ships were freed from the ice. Immediately he set sail for the strait that the Inuit assured him was there. And within two months he found it, naming it the Fury and Hecla Strait. But, to his dismay, he also discovered that huge ice floes made it impassable. Leaving the ship, he explored the area on foot, and from a high vantage point spotted the open body of water to the west.

But it was miles away, his passage was blocked, and winter was setting in. He had no choice but to put into a harbor at Igloolik Island and make preparations for another long stay in the ice. Even for the always-optimistic Parry it was almost too much. “It required but a single glance at the chart,” he confided to his journal, “that whatever the last summer's navigation has added to our knowledge of the eastern coast of America, and its adjacent lands, very little had, in reality been effected in furtherance of the North-West Passage. Even the actual discovery of the outlet into the Polar Sea, had been of no benefit in the prosecution of our enterprise; for we had only discovered this channel to find it impassable, and to see the barriers of nature impenetrably closed against us to the utmost limit of the navigable season.”

At this point, both ships were running short of supplies. And there was an even more serious problem. Nine of the

Fury's

crewmen were suffering from scurvy. (Scurvy had plagued sailors since the 1500s; see note, page 260). One of the officers aboard the

Hecla

had died from the affliction. Parry ordered Lyon to sail his vessel back to England as soon as the ice broke up. Once he was free from the ice, Parry would make one last try at penetrating the Fury and Hecla Strait. But this final attempt proved as futile as the first. The strait was still blocked and a disappointed Parry headed for home.

His second voyage had not been without its accomplishments. He had learned much about the Inuit and their ways. And once again he had discovered a promising channel that might be a gateway to the passage. But once again, the hopes he shares with Barrow for a quick discovery had been dashed. He arrived back in England in the second week of October 1823, only to discover that Franklin had returned from his overland trek a year earlier to even greater acclaim than he himself had received after his first passage-seeking voyage. For the proud Parry, it was almost as big a disappointment as not having found the passage.

It did not take long for the disappointment to turn into renewed hope. While he had been away, Parry had been promoted to the rank of captain. He had also been appointed acting hydrographer of the Admiralty. But he had accepted this position only on the condition that it would not preclude his being given the opportunity to make yet another attempt to find the passage. He soon got his chance. In January 1824, he was again given command of the

Hecla

and the

Fury.

This time his orders were to sail through Lancaster Sound, proceed down Prince Regent Inlet, and then search for the pathway to the passage along the northern coast of North America.

But this time there would be no promising beginning to the voyage. Arriving at Baffin Bay on the way to Lancaster Sound, Parry found the ice so thick that he fell weeks behind schedule. Once in the sound, he was forced to battle winds so fierce that they actually drove his ships backwards at times. Through sheer determination and no small amount of navigational skill, the expedition was finally able to reach Port Bowen on the east coast of Prince Regent Inlet. But by this time Parry's old nemesis winter had once again set in. For the third time in less than five years he was forced to make his home in the ice.

Bigger troubles lay ahead. In July 1825, when they were once again able to get underway, Parry decided to sail across to the other side of the wide inlet, hoping to find yet another new passageway to the west. He was only ten days into this journey when he was once again battered by heavy winds. This time he did not escape. As both ships were being blown toward land, an iceberg struck the

Fury

, throwing it against the ice that lined the shore. The vessel was so badly damaged that even around-the-clock manning of the pumps could not prevent the vessel from continually taking on water. Parry knew that with no harbor in the vicinity, repairs, if possible, would have to be made on the spot. He ordered that the

Fury's

supplies be unloaded on the beach and that the ship's crew be transferred to the

Hecla.

Then the men of both vessels attempted to secure the

Fury

in a position where repairs could be made. But just as they were beginning this effort, they were hit with a series of blizzards. When these were followed by yet another storm, Parry ordered that the

Hecla

, with both crews aboard, be sailed southward to avoid the same fate as had befallen its sister ship. Four days later, after the winds had abated, the sailors returned to the

Fury

, only to find the ship on the beach, lying on her side. Nothing could be done but abandon her.

Noting in his journal that “the only real cause for wonder is our long exception from such a catastrophe,” Parry returned to England where Barrow was not so quick to gloss over the fact that, this time, nothing had been achieved. “Parry's third voyage,” he wrote, “has added little or nothing to our stock of geographical knowledge.” He meant the Northwest Passage.

Although he would never again be given the opportunity of seeking the prize, Parry's days in the Arctic were still not over. In 1827, accompanied by Lieutenant James Clark Ross (John Ross's nephew), Parry headed an expedition seeking to accomplish what David Buchan had failed to doâfind the North Pole. Sailing to Spitsbergen, Parry and his party of fourteen men attempted, beginning on June 21, to sledge their way to the Pole. But instead of encountering the flat, unbroken plain of ice that he had expected to find, Parry once again was confronted with rapidly moving packs of ice. By July 26, conditions had so deteriorated that the quest had to be abandoned. Parry, however, had reached latitude 82°45' north, a record that would stand for the next forty-nine years.