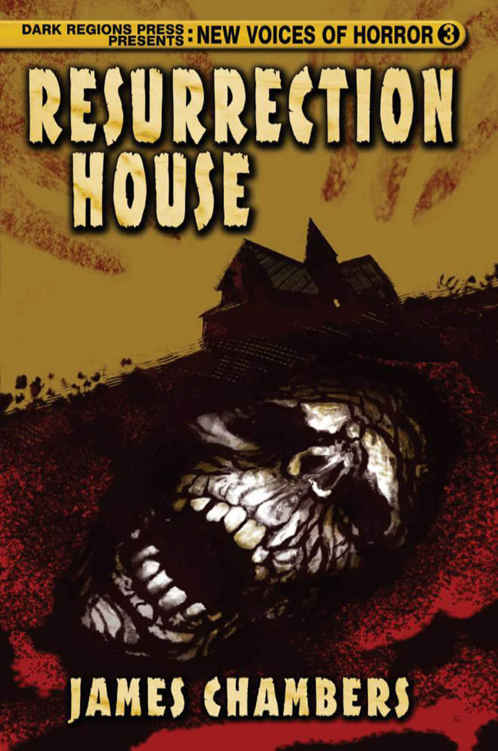

Resurrection House

Read Resurrection House Online

Authors: James Chambers

James Chambers

This eBook edition published 2012 by Dark Regions Press as part of Dark Regions Digital.

Dark Regions Press

300 E. Hersey St.

Suite 10A

Ashland, OR, 97520

© 2012

James Chambers

Premium print signed limited editions available at:

www.darkregions.com/books/resurrection-house-by-james-chambers

Dark Regions Presents: New Voices of Horror 3

James Chambers

Resurrection House

Copyright © 2009 by James Chambers

“The Feeding Things,” Copyright © 2006 by James Chambers, first published in

Cthulhu Sex

# 23, 2006.

“Gray Gulls Gyre,” Copyright © 2005 by James Chambers, first published in

Dark Furies

, 2005.

“The Last Stand of Black Danny O’Barry,” Copyright © 2002 by James Chambers,

Weird Trails

, 2002.

“Mooncat Jack,”

Copyright © 2002 by James Chambers, first published in

Mooncat Jack

, 2002.

“Refugees,” Copyright © 2004 by James Chambers and Vince Sneed, first published in

Allen K’s Inhuman

# 1, 2004.

“Resurrection House,” Copyright © 2004 by James Chambers, first published in

The Dead Walk

, 2004.

“The Tale of the Spanish Prisoner,” Copyright © 2002 by James Chambers, first published in

Warfear

, 2002

“Trick,”

Copyright © 2002 by James Chambers, first published in

Mooncat Jack

, 2002

My deepest thanks go to those who have supported my work over the years with their encouragement and feedback, especially Danielle Ackley-McPhail, Bloody Mary, Melanie Chambers, Stephanie Chambers, Jeff Edwards, Patricia Herrmann, HorrorWench, Adam P. Knave, Ronald Damien Malfi, Mike McPhail, Christopher Mills, Ariana Osborne, Daniel Robichaud II, Stanley C. Sargent, Matthew Dow Smith, Robert Smith, Bill Wiebking, Joe Williams, and Peter Worthy; thanks to CJ Henderson and Vince Sneed for their help in making this book a reality and for their friendship; and thanks to the editors and publishers who first let many of the stories here see the light of day: Michael Amorel, Oliver Baer, Kevin L. Donihe, Bruce Gehweiller, Allen Koszowksi, John Edward Lawson, and Michael Szymanski. Special thanks go to Joe Morey for his confidence in my writing and his guidance through preparing this book for publication, to Bobbi Sinha-Morey for her sharp-eyed editing, and to designer, David Barnett. Thanks, too, to Jason Whitley, illustrator extraordinaire, fellow Robert Aickman fan, and my collaborator in

The Midnight Hour

. My heartfelt thanks go to my wife, Laurie, and my children for not being frightened by my nightmares. This book is for Mom and Dad.

Cruel as it might seem on the surface, there is something about a destructive, abusive, can’t-stand-to-be-part-of-it-anymore lifestyle that twists and injures children in a manner that sometimes gifts them with the potential for being terrific writers. Look into the backgrounds of many of the greats and you find a litany of reprehensible parenting or other traumatic experiences that would sadden the darkest heart.

Broken marriages; evil stepparents; horrific beatings; sexual misconduct, on the part of relatives and approved, outside forces; religious fanaticism; alcohol and drug misuse; uncaring, anti-intellectual school systems, et cetera. The list of monstrous terrors which can be visited upon children, spirit-shattering horrors which can twist their souls and permanently color their outlooks to the point where they can barely function in normal society often ruin their adult lives. But sometimes…

sometimes

these things are fabulous building blocks for creative talent. Because people pushed that hard must learn to cope with the darkness all around them. And one way to do that is by channeling their rage, hurt, and fear into art, music, or writing.

It should come, then, as no surprise that people who travel down this path often wind up writing…

horror

stories. What may come as a surprise, though, are the people like James Chambers who, apparently denied the benefits of a monstrous upbringing, still somehow managed to struggle forward to where they might have something to say about the darkest realms of human existence. Incredible as it may sound to those of you familiar with the lives of, oh say, H.P. Lovecraft or Robert E. Howard, these people are out there. They exist. Writing their terrifying stories seemingly without an ounce of inner torment to draw upon to do so as if it were the most natural thing in the world. Yes, I know--that sounds utterly improbable on the surface, and yet, it’s true. I know it’s true. I’ve seen it. In fact—

You’re holding a whole book full of such stuff right now.

James Chambers is one of these strange writers, a chap without benefit of a rotting liver or drug addiction, born into a family reputed to be happy, now living with a charming wife and two adorable children, but who can still type up a tale so blood-curdling, so twisted in its insights, so malevolent in its intent that you would think its author simply had to be maladjusted, or, like Richard Upton Pickman, possessed the ability to summon the darkest demons of the netherworld into their basement purely for artistic inspiration.

I have a theory. In nature there is a level of sound called the resonant frequency. This is the pitch that must be reached for any form of audible vibration to be able to shatter glass. Whether produced by a machine or the human voice, it is this one single decibel that, when reached, allows a note only slightly different from all those around it in any direction to become a thing of glorious power. It is my contention that all of life has its resonant frequency. Whether one is a baker, auto mechanic, rodeo clown, or whatever, there is a certain degree of proficiency which must first be met before one can hang out their shingle. Beyond that, time must be spent practicing and honing one’s craft if for no other reason than to simply be able to continue to compete with others in the same field.

But, there are those others, those few, who are gifted from birth with the ability to reach the resonant frequency, to hit the high note with exacting precision and singular clarity. Theirs is a talent unnatural, perhaps supernatural--a gift from the gods, as it were, and it is frightening in its power. James Chambers is one of these few. His stories are far and away among the best our modern century has to offer to future generations. Some are passionate. Some are creepy. Some are twisted and terrifying. All of them are excellent. Chambers is a craftsman of the highest caliber. It would be an insult to him to pretend these tales of his flow like water from a tap. No, he doesn’t have it that easy. Having known him for quite some number of years now, I can attest that he does put in his time. He works hard, sweats over word choices and sentence structure, labors the same long hours as the rest of us. The difference is, when he is done, when he sits back to review his work, when his hand has finally released his bowstring and allowed his arrow flight, he finds he has pierced the bull’s eye each and every time. I could prattle on for quite some time longer. As one of your typical procrastinating authors, I would much rather ramble on here than do my own work. But, that’s the attitude that separates guys like me from the one you’re about to read. Is James Chambers the greatest horror writer of our time? Well, I don’t know. I haven’t read every work by everyone out there, so I wouldn’t begin to know how to answer that question. But, what I do know is, no matter who in the field I haven’t come across, no matter which novels or short stories I might have missed, what I can tell you with the most assured confidence is that he is certainly one of the greatest--past, present, or to come. The book you are holding is stuffed with some of the most wonderfully chilling tales you will ever read. Thoughtful, engrossing, tear-provoking, just plain excellent. This is a hand-picked selection of stories from one of the finest writers working today. In time, perhaps, it will be the revered stuff of legend.

It is the work of a writer, who, seemingly without benefit of a tortured soul, has tapped into the resonant frequency to tell his dark and disturbing tales. But, then, come to think of it, the neighbors always say the serial killer next door seemed like such a nice guy. And I’ve never actually visited Mr. Chamber’s basement…

So, perhaps, there’s more to the story than meets the eye. Whatever the case may be, you, my friend, are about to launch yourselves into one of the greatest reading experiences of your lives.

Enjoy!

C.J. Henderson

Brooklyn, NY 2009

The first time I heard about Mooncat Jack he whispered into our lives like a tradition born overnight. It was our second day back at school after Christmas break the year I turned twelve. That year Richie Perullo, who sat two seats behind me, didn’t come back from vacation. The day after Christmas Richie took his little brother skating on Cherry Hill Pond, and Jimmy broke through a thin patch of ice and got trapped underneath. My best friend Wilt Corman was there when it happened. The way I heard it Richie and Wilt flattened out and formed a kind of half-assed, two man human chain with Wilt’s bony legs stretching toward shore and Richie soaking himself trying to fish out his kid brother. By the time they ran for help, Jimmy had been under too long and Richie was blue from hypothermia.

Those two used to fight all the time — Jimmy was three years younger and Richie used to kick the daylights out of him—but you almost never saw them apart.

Despite the wicked cold snap that set in after New Year’s, they sent us outside for recess that whole week. The dry cold made our noses run. A few kids rallied to get a kickball game going, but our lungs burned if we ran too much and no one wanted to chase the ball. At Holy Mother the parking lot doubled as a playground and there wasn’t much to do but huddle together and kick around chunks of snow until they disintegrated.

That’s when Wilt told us what really happened out on the ice the day Jimmy died.

“Mooncat Jack was there,” he said. “He grabbed Jimmy and pulled him under the water, grabbed him right out of Ronnie’s hands. I saw him. He was smiling when he did it.”

It felt sad and kind of weird not having Jimmy and Richie around anymore, so no one wanted to be too hard on Wilt, but none of us believed him. Maybe we figured he made it up to feel better about not saving Jimmy, or maybe he did it for attention.

That’s what Susie McKinney thought, anyway. “You’re, like, unhinged, Wilton,” she told him. “Mentally, I mean.”

Eddie Spirowski mimicked her, pointing his index finger at his head and spinning it in circles. “Yeah, dude, un-hinged! Totally mental!”

Wilt shut up then, no comeback, no defense, and everyone laughed.

The only kid other than me who didn’t make fun of him was Joey Reagan, who said he knew about a kid in Center Quogue who went missing and later they found his body in the woods by the parkway. Mooncat Jack stole him out of his bedroom, he said. The girl who found the body claimed she saw Jack dump it, but when the police came, they couldn’t find anyone. Joey said Mooncat Jack went around taking kids no one was watching or kids that no one wanted or someone wanted gone. He took them in the dark, laughing and smiling with teeth like black dice and eyes that might look like empty sockets or pools of dead water waiting to suck people down inside them. The Mooncat, he told us, dressed completely in black.

We all got quiet listening to the story, but none of us bought it. Joey was kind of dim. He forgot his homework a lot and did things like staying up late studying history the night before an English test. Everybody knew he was chicken and would’ve jumped out of his skin if he thought Mooncat Jack was real.

“If he takes kids no one wants,” Eddie said, “then why don’t he take you, Joey?”

Eddie’s joke broke the spell, and we let Joey have it.

Wilt drifted away, forgotten for the moment. No one wanted to rag on him too much because he’d been right there when Jimmy died, but Joey was a big fat apple waiting to be picked. Thing was he had a good sense of humor and was popular, so he knew we were only kidding. At least until Spirowski made a crack about his mother. That earned Eddie a place at the bottom of a pile-on, face down, rolling around in the gravel-stained snow. Wilt watched from the sidelines, a slanted phony grin on his face, and tried to look like he belonged, but a deep shadow hung over him and his laugh crackled like a mean, dry cough.

A few days later I walked home with Wilt from the drugstore near school after playing Defender and Berzerk for a quarter a game. We both liked Donkey Kong better, but it cost fifty cents and we were short on change. I asked Wilt if he really meant what he said about Mooncat Jack.

He told me he just made it up like Susie said. He got it from dreams he had where he saw an ugly man hiding in the curtains or under the basement stairs, grinning and waiting to grab him. In some of the dreams Wilt was hiding, quaking as he listened to the man shuffle closer until he could feel him standing right by his side. He called him Mooncat Jack, but he probably picked the name up from Joey Reagan’s dumb stories. The dark man was just a bad dream, he said, and sooner or later he would go away. Bad dreams always did.

Wilt hung his head and kicked an ice chunk the size of a golf ball along in a crooked line until it bounced over the curb and sailed out of sight between the tines of a sewer grate.

“I’d believe you if you say it’s true,” I told him. “I mean it. Really.”

We’d been friends since kindergarten, and I was worried he might be sick. Since coming back from break he always looked pale, and he ran out of energy too fast and fell asleep in class in the afternoon. But Wilt had been kind of sad for a while even before what happened with Jimmy. Something bad went wrong between his parents and they had split up over the summer. Now Wilt only saw his father a couple of times a month. Mr. Corman was a big, gravel-voiced man with one eye always twitching, and he favored a heavy overcoat that floated around him like a furry sail. I could usually tell when Wilt was going to see him on the weekend because he got quiet and sullen toward the end of the week. Wilt was the only kid I knew whose parents were divorced. It made him sort of an oddball in our class.

What I didn’t know, then—what no one our age knew, then—was that for months rumors had traveled like dervishes among our parents and neighbors about the real reason the Cormans got divorced. The adults whispered words like “touching” and “abuse” and said Mrs. Corman was living “in denial.” Most of them thought it a matter of time before the police showed up outside the Corman house, and fathers who had business with Wilt’s dad slowly let it dry up. All I knew was that in the fourth grade my dad stopped letting me spend much time at Wilt’s house, though he let Wilt come over to our place whenever he wanted.

After we trudged on in silence for a while, I asked, “You still coming Saturday?”

Wilt slugged me in the arm. “Duh, why wouldn’t I? It’s your birthday, isn’t it?”

“Yeah, cool!” I’d thought he might not want to go to a party and see everyone have fun, but maybe it would cheer him up.

Wilt checked his watch as we came down North Park Street. “I’m gonna be late,” he said, and we hauled butt down the road.

Wilt’s mother gave him a curfew anytime he went anywhere and made his life miserable if he wasn’t home on time, so Wilt was eternally watching the clock when we hung out. Sometimes, if he was going to be late, he had to ask to use the phone at our house to call his Mom just so she knew where he was. It didn’t save him from a scolding, but it helped.

Wilt raced up his front path and yanked the door open. He stuck his head in and yelled that he was home over the television noise barreling out of the living room. His grandmother liked to watch the tube with the sound turned up full volume.

Wilt twisted around in the opening, winded from running but glad to be in under the wire. He waved once, then slipped inside and slammed the door behind him.

I walked up the street toward home, taking my time in the twilight. The thickening dark leeched the color from the houses and trees, turning everything into sharp black shapes like the silhouettes we made out of construction paper in the third grade. I used to like that time of day, when it felt like I could slip away giggling into those unlit spaces where I imagined I could watch the world roll by, listen to everyone’s secrets, and go wherever I wanted without ever being seen. Thinking about it made me feel confident and a little giddy, and I swore I would find that place one day. I meant it, too. Strange how we see the world sometimes, how near at hand a getaway can seem when really it’s light years distant and maybe doesn’t exist at all.

Coming around the corner of my block I thought I saw my Dad cross our front lawn and turn past the side of the house, looking up like he was checking the gutters or the snow gathered on the roof. But it must have been a trick of the light or old Mr. Rollins who lived next door, because Dad’s car wasn’t in the driveway when I got there, the signal that he was working late. A porch light burned inside an amber sconce beside our front door. Its twin above the side door lit the driveway. The smell of dinner cooking drifted from the kitchen vent, and through the window I saw Mom standing at the oven. Matty sat at the kitchen table, coloring with his crayons and drinking milk. He sniffled and Mom handed him a tissue, not missing a step between the stove and the sink.

I looped my backpack over the door handle, jumped off the stoop and crunched into the yard. Our back lawn ran to a stream that cut through our property, and I chugged down to the bank where ledges of snow had frozen into crisp overhangs melted away underneath by flowing water. I wandered along, kicking them loose and watching them splash into the weak current where they melted before they sank. When the last one vanished I tossed rocks into the stream and packed dirty snowballs and hurled them as hard as I could into the woods. Most hit the ground and broke apart. A few shook dead branches loose, but the best were the ones that smacked loud and square against a tree trunk. A hit like that left half a snowball clinging to the thick bark, and in the dark they looked like the tiny scalps of ghostly babies struggling to be born from the knothole wombs of the trees, white and frozen in time, trapped dead before they ever began to live.

I stayed out back until my fingertips went a little numb and my stomach started grumbling. The sky had turned black, by then, and it glittered with stars.

Matty already had his face in a dish when I walked in. I hung my coat in the closet and left my backpack at the foot of the stairs. Mom filled a plate for me while I took a fork and knife from the drawer, grabbed a napkin and a glass, and sat down. After two bites of baked chicken I got up and took the milk pitcher from the refrigerator. Matty stuck his cup out for me to refill and I poured it halfway.

He slurped it down, his mouth half-full of food.

“Did you see Matty’s new painting?” Mom asked me. She pointed at the water-wrinkled paper pinned by a magnet to the refrigerator and decorated with a colorful collection of crude smears that suggested a house with a dog in the yard. A selection of Matty’s greatest hits from kindergarten surrounded it. “Mrs. Brady said it was the best of anyone in his class.”

I nodded at my little brother. “Oh, that’s great. Good job, Matty.”

Matty smiled, and then crammed a giant forkful of mashed potatoes between his small lips. It was almost more than he could handle. I thought he might choke, but then who the hell ever choked on mashed potatoes?

Dad’s car rumbled up the driveway while we ate, and the engine clanked off. He worked late at the bank, hoping for a promotion to vice president; he’d been passed over twice before and needed to put in the extra time to look good. He hated the idea of being stuck forever opening new accounts and helping people apply for mortgages, and Mom sure wasn’t thrilled with it, either. It was tough, though, because the president liked to hire his family and business was slow with the economy down, making it hard for Dad to get hired at another bank. I don’t think he much liked his job. One time he suggested moving to another town or into the city, and Mom stopped talking to him for the rest of the night. They didn’t discuss it often, but I heard a lot when they thought I wasn’t listening and I understood most of it, too.

Taking his hat off as he entered, Dad let the side door swoosh shut behind him and slowed to say hello on his way through the kitchen. He rustled around in the bedroom, and when he came back he had removed his tie and his shirt collar hung open. He loaded his plate and sat beside Mom. Right away she pointed out Matty’s artwork. Mustering a look of admiration Dad told Matty he was one talented little artist.

Matty giggled. He liked it when Dad made a big deal of him.

Mom asked me if Richie Perullo had been back to school. No one had seen him since Jimmy’s funeral, and word was he’d transferred to some kind of special school with more doctors than teachers.

“Poor Mrs. Perullo. Her whole life shattered like that,” she said and shook her head. “Richie and Jimmy were close, weren’t they?”

“Sure,” I said. “Richie beat Jimmy up a lot.”

“They were brothers. Of course, they were close,” said Dad. He winked at me. “So, big day coming up this weekend, huh?”

I mumbled something like “I guess,” but I couldn’t help the smile creeping into my face.

“You guess?” he said, feigning disappointment. “Well, I suppose when you hit the ripe old age of twelve, birthdays start to seem pretty much the same from year to year.”

“Is everyone coming?” asked Mom.

“Wilt said he’s coming,” I said. “I think everyone else is, too. There were a lot of other kids I wanted to ask, Mom.”

“I told you I don’t want an army trooping in and out of the house all day.”

Matty turned five last June and most of his class spent the day celebrating in the backyard while Dad barbecued. They stayed until it got dark enough to light sparklers and chase fireflies through the bushes. About half a dozen of Matty’s friends spent the night. They took over our room and I slept on the couch.