Return to Night (40 page)

Authors: Mary Renault

There would be no time to overtake him, either on his way, or after, when a running dive had carried him into the covered water under the rock. He stood for a moment with his shoes in his hand, then pushed them deliberately into the pockets of his jacket, and began to strip it off. Suddenly she knew the only thing that was left to do, with any certainty of checking him. Reaching up to the switches just above her head, she put out the light.

She heard the wet thud of his weighted coat on the ground, then stillness. It was all clear to her now. She crossed quickly to the throne of rock, while she still remembered distance and direction; groped, felt it under her hand, and sat down.

“Julian,” she called softly. “Julian.”

She heard him move; but so slightly that she could not tell which way he was going, and a terror seized her that, in his familiarity with the place, the darkness might be no hindrance to him. Forcing her voice into control, she said again, “Julian. Come here to me.”

As she ended the last word, one of his hands brushed her. She reached out for him, and would have risen; but already his head and arms were on her knees.

The cold of his body horrified her; he might have been already drowned. As once before, she gathered the edge of her coat round him; but when it touched him, he began to tremble so violently that it slid away. She took him in her arms, and lifted his head. He began to speak; she could hardly hear, because his teeth were chattering. “I didn’t know I’d done it.”

“Darling. You’re here with me.”

He put up a hand to touch her face and dress; then clung to her, silently. After a few moments he whispered, “Oh God. I’m so cold.”

“Dear, I know.” She covered him with the coat again. “You must come home now. You’ve, been out too long. You’re tired. You must have a hot bath, and a drink, and come to bed.”

He shook his head. His voice muffled in her breast, he was trying to tell her something. She could hear less than half he said. It told her, however, as much as for the present she needed to know. She held him closer, thinking not so much of what she had learned as of what she must do for him; that there was a rug in the car, and the flask of coffee which she had not had tonight, that she must put on the bedroom fire, or perhaps Lisa would have done it already. While her mind ran on these things, she murmured over him without much thought of what she said, the kind of foolishness she had indulged sometimes while he slept. “My dearest boy,” she whispered, “my beloved, my beautiful.”

He made a sudden violent sound; it was like something tearing in him. Pulling his face away from her, he pressed it into his arm. The sound came again, muffled; she could tell that he had shut his teeth on the flesh. She felt painfully helpless. The nurses used to say to women, “Have a good cry, dear; it will make you feel better.” But though she had heard men groan often, and had once heard a man scream, she had never heard one cry, and found that she did not know whether it made them feel better or not. Judging by what she had just heard, it seemed unlikely. “There, my darling,” she said uncertainly; “you’re tired and cold. You’re not well. I’ll take you home.”

“No.” His breath caught; he stopped till he was ready. “I’m no good.”

“I love you; what about me?”

“I’m no good to anyone.”

She stopped thinking. She loosened her dress to make a warmer place for his head, and took him into it. The words seemed not to come from her mind, but from some deep place in her body, as blindly and certainly as a caress in the night.

“You’re the best of all. You’re what I wanted always. Before you were born I wanted you, and all your life. I always wanted him to be just like you.”

She was a fool, she decided next moment; she had only made things worse. But it came to him more easily now. He was starved with cold, she thought; it was draining the life out of him, he would be comforted if he were warm. So she slipped down beside him, onto the step of rock below the throne, where she could be nearer. At first he grew tense as if he were afraid, and began to shiver again: he had gone a long way, tonight, into his private world. She made him as comfortable as she could, leaning against the cold stone; and after a while he lay half relaxed and still; cautiously still, like a child who expects, if he gets himself too much noticed, to be sent away. But through his wet shirt he began to seem a little more like the living; and at last she felt against her breast the faint movement of a kiss. It was guarded, almost stealthy; not like a caress, like a half-hearted worthless claim that will be seen through and rejected, hardly worth making. It filled her with impotent anger; but that was done with, and had never been of use. She said, “I love you. Better than anyone,” and kissed him.

Soon they must go, but with his head in her arm she stayed for a little longer. He was quiet and, it seemed, at rest, and she could not bring herself yet to stir him into effort again. Weary herself, she let her mind drift, and found it wander to the hours before she had gone in search—of him; strangely, it seemed now as if all that while she had been seeking him still. It was true, she thought; for the second time that night she had listened to the resisting cry of birth. But this time it would cost her more. This time she was completing it not with her hands but in herself, it was she who had it still before her to suffer and be torn. What she had now was not for her possessing. She was only the Madonna of the Cave, Demeter who fashions living things and sends them out into the light. All she had done, and had still to do, would work to accomplish her own loss; to separate and free him, to make him less a part of her, and more his own. Already the new claimants were waiting to receive him from her; the dangers of the coming years; death, perhaps, not this that he would have chosen but alien and lonely; if he lived, the work which would be his most demanding love; the men who would be his friends; the women who would be beautiful when the last of her youth was gone. Lisa had found an answer, but that was not for her. She would never bear a child to him. It would be too long before she could spare for its needs the love of which his own need had never been satisfied; before his mind was ready, her body would be too old.

He stirred in her arms. “Now you’re getting cold, too.”

“This is a cold place, darling. Let’s go home.”

He got to his knees beside her, and took her in his arms. It was the first kiss, tonight, that he had taken for himself.

“You were frightened,” he said, “when we came here before. Aren’t you frightened now, so late in the night?”

She had forgotten; but she felt what was needed of her. “Yes, I am a little. I’m always afraid of the dark.”

He stood, and lifted her to her feet, taking her weight on his arm. Drawing her face to his shoulder, he patted her hair,

“It’s all right, beloved. See, I’ve got you. There’s nothing to be afraid of, if you just keep a tight hold on me.”

Mary Renault (1905–1983) was an English writer best known for her historical novels on the life of Alexander the Great:

Fire from Heaven

(1969),

The Persian Boy

(1972), and

Funeral Games

(1981).

Born Eileen Mary Challans into a middle-class family in a London suburb, Renault enjoyed reading from a young age. Initially obsessed with cowboy stories, she became interested in Greek philosophy when she found Plato’s works in her school library. Her fascination with Greek philosophy led her to St Hugh’s College, Oxford, where one of her tutors was J. R. R. Tolkien. Renault went on to earn her BA in English in 1928.

Renault began training as a nurse in 1933. It was at this time that she met the woman that would become her life partner, fellow nurse Julie Mullard. Renault also began writing, and published her first novel,

Purposes of Love

(titled

Promise of Love

in its American edition), in 1939. Inspired by her occupation, her first works were hospital romances. Renault continued writing as she treated Dunkirk evacuees at the Winford Emergency Hospital in Bristol and later as she worked in a brain surgery ward at the Radcliffe Infirmary.

In 1947, Renault received her first major award: Her novel

Return to Night

(1946) won an MGM prize. With the $150,000 of award money, she and Mullard moved to South Africa, never to return to England again. Renault revived her love of ancient Greek history and began to write her novels of Greece, including

The Last of the Wine

(1956) and

The Charioteer

(1953), which is still considered the first British novel that includes unconcealed homosexual love.

Renault’s in-depth depictions of Greece led many readers to believe she had spent a great deal of time there, but during her lifetime, she actually only visited the Aegean twice. Following

The Last of the Wine

and inspired by a replica of a Cretan fresco at a British museum, Renault wrote

The King Must Die

(1958) and its sequel,

The Bull from the Sea

(1962).

The democratic ideals of ancient Greece encouraged Renault to join the Black Sash, a women’s movement that fought against apartheid in South Africa. Renault was also heavily involved in the literary community, where she believed all people should be afforded equal standard and opportunity, and was the honorary chair of the Cape Town branch of PEN, the international writers’ organization.

Renault passed away in Cape Town on December 13, 1983.

Renault in 1940.

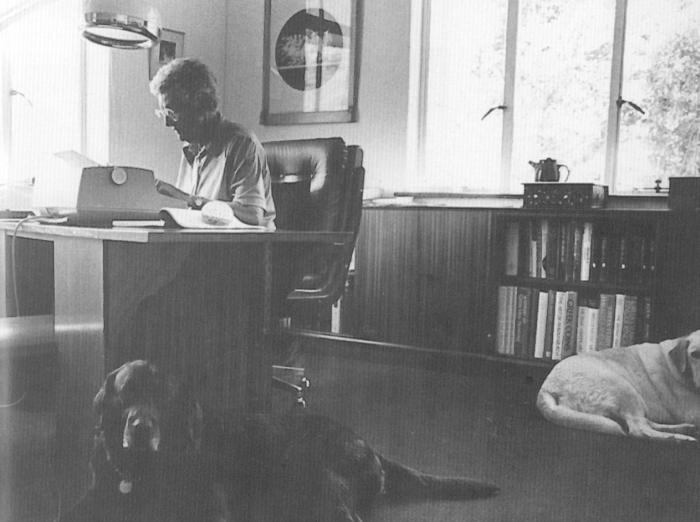

Renault and Julie Mullard on board the

Cairo

in 1948, on their way to South Africa, where they settled in Durban.

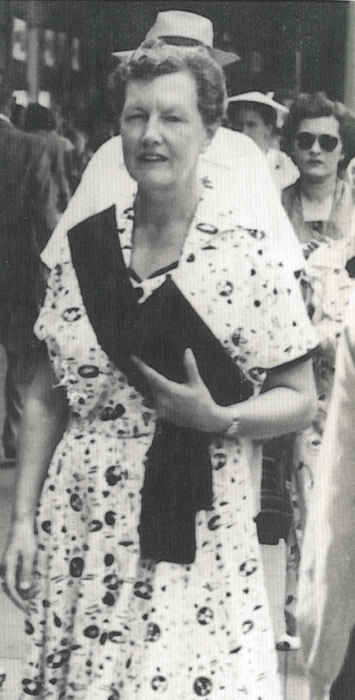

Renault in a Black Sash protest in 1955. She was among the first to join this women’s movement against apartheid.

Renault and Michael Atkinson installing her cast of the Roman statue of the Apollo Belvedere in the garden of Delos, Camps Bay, in the late 1970s.