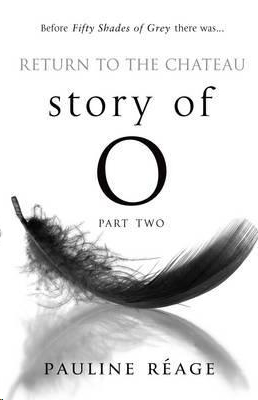

Return to the Chateau

Read Return to the Chateau Online

Authors: Pauline Reage

Tags: #Fiction, #Classics, #Erotica, #Psychological

Return to the Chateau, by Pauline Reage (Story of O Part II)

Return to the Chateau

ONE DAY A girl in love said to the man she loved: “I could also write the kind of stories you like..?” “Do you really think so?” he answered. They met two or three times a week, but never during vacations, and never on weekends. Each of them stole the time they spent together from their families and their work. On afternoons in January and =46ebruary when the days begin to grow longer and the sun, sinking in the west, tints the Seine with red reflections, they used to walk along the on banks of the river, the quai des Grands Augustins, the quai de la to Tournelle, kissing in the shadow of the bridges. Once a clochard shouted at them: “Shall we take up a collection and rent you a room?” Their places of refuge often changed. The old car, which the girl drove, took them to the zoo to see the giraffes, to Bagatelle to see the irises and the clematis in the spring, or the asters in the fall. She noted the names of the asters-blue fog, purple, pale pink-and wondered why, since she was never able to plant them (and yet we shall have further occasion to refer to asters). But Vincennes, or the Bois de Boulogne, is a long way away. In the Bois you run into people who know you. Which, of course, left rented rooms. The same one several times in succession. Or different rooms, as chance would have it. There is a strange sweetness about the meager lighting of rented rooms in hotels near railroad stations: the modest luxury of the double bed, whose linen you leave unmade as you leave the room, has a charm all its own. And the time comes when you can no longer separate the sound of words and signs from the endless drone of the motors and the hiss of the tires climbing the street. For several years, these furtive and tender halts, in the respite that follows love, legs all entwined and arm unclasped, had been soothed by the kind of exchanges and as it were small talk in which books hold the most important place. Books were their only complete freedom, their common country, their true travels. Together they dwelt in the books they loved as others in their family home; in books they had their compatriots and their brothers; poets had written for them, the letters of lovers from times past came down to them through the obscurity of ancient languages, of modes and mores long since come and gone-all of which was read in a toneless voice in an unknown room, the sordid and miraculous dungeon against which the crowd outside, for a few short hours, beat in vain. They did not have a full night together. All of a sudden, at such and such an hour agreed upon ahead of time-the watch a! ways remained on the wrist-they had to leave Each had to regain his street, his house, his room his daily bed, return to those to whom he wa joined by another kind of inexpiable love, those whom fate, youth, or you yourself had given you once and for all, those whom you can neither leave nor hurt when you’re involved in their lives. He, in his room, was not alone. She was alone in hers.

One evening, after that “Do you really think so?” of the first page, and without ever having the faintest idea that she would one day find the name R=E9age in a real estate register and would borrow first name from two famous profligates, Pauline Borghese and Pauline Roland, one day this girl of whom I am speaking, and rightly so, since if I hay nothing of hers she has everything of mine, the voice to begin with, one evening this girl, instead o taking a book to read before she fell asleep, lying on her left side with her feet tucked up under her, soft black pencil in her right hand, began to writ the story she had promised. Spring was almost over. The Japanese cherry trees in the big Paris parks, the Judas trees, the magnolias near the fountains, the elder trees bordering the old embankments of the tram lines that used to encircle the city, had lost their flowers. The days lingered on forever, and the morning light penetrated at unwonted hours to the dusty black curtains of passive resistance, the last remaining vestiges of the war. But beneath the little lamp still lighted at the head of the bed, the hand holding the pencil raced over the paper without the least concern for the hour or the light. The girl was writing the way you speak in the dark to the person you love when you’ve held back the words of love too long and they flow at last.

=46or the first time in her life she was writing without hesitation, without stopping, rewriting, or discarding, she was writing the way one breathes, the way one dreams. The constant hum of the cars grew fainter, one no longer heard the banging of doors, Paris was slipping into silence. She was still writing when the street cleaners came by, at the first touch of dawn. The first night entirely spent the way sleepwalkers doubtless spend theirs, wrested from herself or, who knows, returned to herself.

In the morning she gathered up the sheets of paper that contained the two beginnings with which you’re already familiar, since if you are reading this it means you have already taken the trouble to read the entire tale and therefore know more about it today than she knew at that time. Now she had to get up, wash, dress, arrange her hair, resume the strict harness, the everyday smile, the customary silent sweetness. Tomorrow, no, the day after, she would give him the notebook.

She gave it to him as soon as he got into the car, where she was waiting for him a few yards from an intersection, on a small street near a metro station and an outdoor market. (Don’t try and situate it, there are many like it, and what difference does it make anyway?) Read it immediately? Out of the question. Besides, this encounter turned out to be one of those where you come simply to say that you can’t come, when you learn too late that you won’t be able to make it and don’t have time to tell the other party. It was already a stroke of luck that he had been able to get away at all. Otherwise she would have waited for an hour and then come back the following day at the same time, the same place, in accordance with the classic rules of clandestine lovers. He said “get away” because they both used a vocabulary of prisoners whose prison does not revolt them, and perhaps they realized that if they found it hard to endure they would have found it just as hard to be freed from it, since they would then have felt guilty. The idea that they would have to return home gave a special meaning to that stolen time, which came to exist outside the pale of real time, in a sort of strange and eternal present. They should have felt hemmed in and hunted down as the years went winging by without bringing them any greater degree of freedom. But they did not. The daily, the weekly obstacles-frightful Sundays without any letters, or any phone calls, without any possible word or glance, frightful vacations a hundred thousand miles from anywhere, and always someone there to ask: “A penny for your thoughts”-were more than enough to make them fret and worry and constantly wonder whether the other still felt the same way as before. They did not demand to be happy, but having once known each other, they simply asked with fear and trembling that it last, in the name of all that’s holy that it last … that one not suddenly seem estranged from the other, that this unhoped-for fraternity, rarer than desire, more precious than love-or which perhaps at long last was love-should endure. So that everything was a risk: an encounter, a new dress, a trip, an unknown poem. But nothing could stand in the way of taking these risks. The most serious to date, nonetheless, was the notebook. And what if the phantasms that it revealed were to outrage her love or, worse, bore him or, worse yet, strike him as being ridiculous? Not for what they were, of course, but because they emanated from her, and because one rarely forgives in those one loves the vagaries or excesses one readily forgives in others. She was wrong to be afraid: “Ah, keep at it,” he said. What happens after that? Do you know? She knew. She discovered it by slow degrees. During the rest of the waning summer, throughout the fall, from the torrid beaches of some dismal watering spot until her return to a russet and burnt-out Paris, she wrote what she knew. Ten pages at a time, or five, full chapters or fragments of chapters, she slipped her pages, the same size as the original notebook, written sometimes in pencil, sometimes in ink, whether ballpoint or the fine point of a real fountain pen, into envelopes and addressed them to the same General Delivery address. No carbon copy, no first draft: she kept nothing. But the postal service came through. The story was still not completely written when, having resumed their assignations back in Paris in the fall, the man asked her to read sections out loud to him, as she wrote them. And in the dark car, in the middle of an afternoon on some bleak but busy street, near the Buttes-aux-Cailles, where you have the feeling you’re transported back to the last years of the previous century, or on the banks of the St. Martin Canal, the girl who was reading had to stop, break off, once or more than once, because it is possible silently to imagine the worst, the most burning detail, but not read out loud what was dreamt in the course of interminable nights.

And yet one day the story did stop. Before O, there was nothing further that that death toward which she was vaguely racing with all her might could do, that death which is granted her in two lines. As for revealing how the manuscript came into the hands of Jean Paulhan, I promised not to reveal it, as I promised not to divulge the real name of Pauline R=E9age, counting on the courtesy and integrity of those who are privy to it to keep the secret as long as I feel bound not to break that promise. Besides, nothing is more fallacious and shifting than an identity. If you believe, as hundreds of millions of men do, that we live several lives, why not also believe that in each of our lives we are the meeting place for several souls? “Who am I, finally,” said Pauline R=E9age, “if not the long silent part of someone, the secret and nocturnal part which has never betrayed itself in public by any thought, word, or deed, but communicates through the subterranean depths of the imaginary with dreams as old as the world itself?” Whence came to me those oft-repeated reveries, those slow musings just before falling asleep, always the same ones, in which the purest and wildest love always sanctioned, or rather always demanded, the most frightful surrender, in which childish images of chains and whips added to constraint the symbols of constraint, I’m not sure which. All I know is that they were beneficent and protected me mysteriously-contrary to all the reasonable reveries that revolve around our daily lives, trying to organize it, to tame it. I have never known how to tame my life. And yet it seemed indeed as though these strange dreams were a help in that direction, as though some ransom had been paid by the delirium and delights of the impossible: the days that followed were oddly lightened by them, whereas the orderly arrangement of the future and the best-laid plans founded on good common sense proved each time to be contradicted by the event itself. Thus I learned at a very tender age that you should not spend the empty hours of the night building dream castles, nonexistent but possible, workable, where friends and relatives would be happy together (how fanciful!)-but that one could without fear build and furnish clandestine castles, on the condition that you people them with girls in love, prostituted by love, and triumphant in their chains. So it was that Sade’s castles, discovered long after I had silently built my own, never surprised me, as I was not surprised by the discovery of his society, The Friends of Crime: I already had my own secret society, however minor and inoffensive. But Sade made me understand that we are all jailers, and all in prison, in that there is always someone within us whom we enchain, whom we imprison, whom we silence. By a curious kind of reverse shock, it can happen that prison itself can open the gates to freedom. The stone walls of a cell, the solitude, but also the night, the solitude, again the solitude, the warmth of the sheets, the silence, free this unknown creature whom we have kept locked up. It escapes us and escapes endlessly, through the walls, the ages, the interdictions. It passes from one to the other, from one age to another, from one country to another, it assumes one name or another. Those who speak in its behalf are merely translators who, without knowing why (why them, why that particular moment in time?), have been allowed, for one brief moment, to seize a few strands of this immemorial network of forbidden dreams. So that, fifteen years ago, why not me?

“What intrigued and excited him, I mean the person for whom I was writing this story,” she went on, “was the relationship it might have with my own life. Could it be that the story was the deformed, the inverted image of my life? That it was the shadow of it borne, unrecognizable, confined like that of some stroller in the midday sun, or otherwise unrecognizable, diabolically elongated like the shadow that stretches before someone walking back from the Atlantic Ocean, over the empty beach, as the setting sun goes down in flames behind him? I saw, between what I thought myself to be and what I was relating and thought I was making up, both a distance so radical and a kinship so profound that I was incapable of recognizing myself in it. I no doubt accepted my life with such patience (or passivity, or weakness) only because I was so certain of being able to find whenever I wanted that other, obscure life that is life’s consolation, that other life unacknowledged and unshared-and then all of a sudden thanks to the man I loved I did acknowledge it, and henceforth would share it with any and all, as perfectly prostituted in the anonymity of a book as, in the book, that faceless, ageless, nameless (even first-nameless) girl. Never did he ask any questions about her. He knew that she was an idea, a figment, a sorrow, the negation of a destiny. But the others? Ren=E9, Jacqueline, Sir Stephen, Anne-Marie? And what about the places, the streets, the gardens, the houses, Paris, Roissy? And what about the circumstances, the events themselves? For these, yes, I thought I knew Ren=E9, for example (a nostalgic first name), was the remembrance, no, the vestige of an adolescent love, rather the hope of a love that never happened, and Ren=E9 had never had the slightest suspicion that I might be capable of loving him. But Jacqueline had loved him. And before she loved him, she had loved me. She had in fact been responsible for being the first to break my heart. Fifteen, we were both fifteen, and she had spent the entire school year chasing me, complaining about my coldness. No sooner had summer vacation come and whisked her away than I awakened from this lack of interest, this coldness. I wrote her. July, August, September: for three full months I watched and waited for the postman, but in vain. And still I wrote. Those letters proved my undoing. Jacqueline’s parents stopped her from seeing me, and it was from her, enrolled in another division, that I learned that “that was a sin.” That what was a sin? What did they have against me? The day is not more chaste … I had reinvented Rosalinde and Celia, in all innocence-who did not last. The fact remains that Jacqueline, this real Jacqueline, figures in the story only by her first name and her fair hair. The one in the story is rather a young actress, pale and overbearing, with whom I lunched one day somewhere on the rue de l’Eperon. The old man who gave her her jewels, her dresses, her car, took me aside and said: “She’s beautiful, isn’t she?” Yes, she was beautiful. I never saw her again. Is Ren=E9 what I might have become had I been a man? Devoted to another, to the point of yielding everything to him, without even finding it anachronistic, this vassal-to-lord relationship? I’m afraid the answer is yes. Whereas the imaginary Jacqueline was the stranger par excellence. It took me a long time to realize, however, that in another life a girl like her-one whom I admired unequivocally-had taken my lover away from me. And I took my revenge by shipping her off to Roissy, I who pretended to disdain any form of vengeance, I took revenge and wasn’t even capable of realizing it. To make up a story is a curious trap. As for Sir Stephen, I saw him, literally, in the flesh. My current lover, the one I just mentioned, pointed him out to me one afternoon in a bar near the Champs Elys=E9es: half-seated on a stool at the mahogany bar, silent, self-composed, with that air of some gray-eyed prince that fascinates both men and women-he pointed him out to me and said: “I don’t understand why women don’t prefer men like him to boys under thirty.” At the time he was under thirty. I didn’t respond.’ But they do prefer them. I stared for a long time at the unknown man, who wasn’t even looking at me.