Revenge of the Rose

Read Revenge of the Rose Online

Authors: Michael Moorcock

THE REVENGE

OF THE ROSE

THE REVENGE OF THE ROSE (1991)

For Christopher Lee—

Arioch awaits thee!

For Johnny and Edgar Winter—

rock on!

For Anthony Skene—

in gratitude.

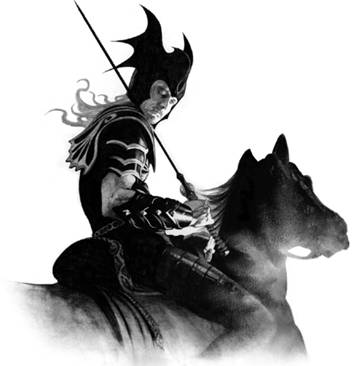

Elric

could enjoy the tranquility of Tanelorn only briefly and then must begin his

restless journeyings again. This time he headed eastward, into the lands known

as the Valederian Directorates, where he had heard of a certain globe said to

display the nations of the future. In that globe he hoped to learn something of

his own fate, but in seeking it he earned the enmity of that ferocious horde

known as the Haghan’iin Host, who captured and tortured him a little before he

escaped and joined forces with the nobles of Anakhazhan to do battle with

them …

—The

Chronicle of the Black Sword

Contents

BOOK ONE

CONCERNING THE FATE OF EMPIRES

BOOK TWO

ESBERN SNARE; THE NORTHERN WEREWOLF

BOOK THREE

A ROSE REDEEMED; A ROSE REVIVED

BOOK ONE

CONCERNING THE FATE OF EMPIRES

“

What? Do you call us decadent, and our whole

nation, too?

My friend, you are too stern-hearted for

these times. These times are new

.

Should you discern in us a selfish introspection;

a powerless pride:

In actuality, self-mockery and old age’s

wisdom is all that you descry!

”

—Wheldrake,

Byzantine

Conversations

CHAPTER

ONE

Of

Love, Death, Battle & Exile; The White Wolf Encounters a Not Entirely

Unwelcome Echo of the Past

.

FROM

THE UNLIKELY peace of Tanelorn, out of Bas’lk and Nishvalni-Oss, from

Valederia, ever eastward runs the White Wolf of Melniboné, howling his red and

hideous song, to relish the sweetness of a bloodletting …

… It

is over. The albino prince sits bowed upon his horse, as if beneath the weight

of his own exaggerated battle-lust; as if ashamed to look upon such profoundly

unholy butchery.

Of

the mighty Haghan’iin Host not a single soul survived an hour beyond the

certain victory they had earlier celebrated. (How could they not win, when Lord

Elric’s army was a fragment of their own strength?)

Elric

feels no further malice towards them, but he knows little pity, either. In

their puissant arrogance, their blindness to the wealth of sorcery Elric

commanded, they had been unimaginative. They had guffawed at his warnings. They

had jeered at their former prisoner for a weakling freak of nature. Such

violent, silly creatures deserved only the general grief reserved for all

misshaped souls.

Now

the White Wolf stretches his lean body, his pale arms. He pushes up his black

helm. He rests, panting, in his great painted war-saddle, then takes the

murmuring hellblade he carries and sheathes the sated iron into the softness of

its velvet scabbard. There is a sound at his back. He turns brooding crimson

eyes upon the face of the woman who reins up her horse beside him. Both woman

and stallion have the same unruly pride, both seem excited by their

unlooked-for victory; both are beautiful.

The

albino reaches to take her ungloved hand and kiss it. “We share honours this

day, Countess Guyë.”

And

his smile is a thing to fear and to adore.

“Indeed,

Lord Elric!” She draws on her gauntlet and takes her prancing mount in check. “But

for the fecundity of thy sorcery and the courage of my soldiery, we’d both be

Chaos-meat tonight—and unlucky if still alive!”

He

answers with a sigh and an affirmative gesture. She speaks with deep

satisfaction.

“The

host shall waste no other lands, and its women in their home-trees shall bear

no more brutes to bloody the world.” Throwing back her heavy cloak, she slings

her slender shield behind her. Her long hair catches the evening light, deep

vermilion, restless as the ocean as she laughs, while her blue eyes weep; for

she had begun the day in the fullest expectation that the best she could hope

for was sudden death. “We are deeply in your debt, sir. We are obligated, all

of us. You shall be known throughout Anakhazhan as a hero.”

Elric’s

smile is ungrateful. “We came together for mutual needs, madam. I was but

settling a small debt with my captors.”

“There

are other means of settling such debts, sir. We are still obliged.”

“I

would not take credit,” he insists, “for altruism that is no part of my nature.”

He looks away into the horizon where a purple scar washed with red disguises

the falling of the sun.

“I

have a different sense of it.” She speaks softly, for a hush is coming to the

field, and a light breeze tugs at matted hair, bits of bloody fabric, torn

skin. There are precious weapons and metals and jewels to be seen, especially

where the Haghan’iin nobles had tried to make their escape, but not one of

Countess Guyë’s sworders, mercenary or free Anakhazhani, will approach the

booty. There is a general tendency amongst these weary soldiers to drop back as

far as possible from the field. Their captains neither question them on this

nor do they try to stop them. “I have the sense, sir, that you serve some Cause

or Principle, nonetheless.”

He

is quick to shake his head, his posture in the saddle one of growing

impatience. “I am for no master nor moral persuasion. I am for myself. What

your yearning soul, madam, might mistake for loyalty to person or Purpose is

merely a firm and, aye,

principled

determination to accept responsibility only for myself and my own actions.”

She

offers him a quick, girlish look of puzzled disbelief, then turns away with a

dawning, woman’s grin. “There’ll be no rain tonight,” she observes, holding a

dark, golden hand against the evening. “This mess’ll be stinking and spreading

fever in hours. We’d best move on, ahead of the flies.” She hears the flapping

even as he does and they both look back and watch the first gleeful ravens

settling on flesh that has melted into one mile-wide mass of bloody meat, limbs

and organs scattered at random, to hop upon and peck at half-destroyed faces

still screaming for the mercy laughingly denied them as Elric’s patron Duke of

Hell, Lord Arioch, gave aid to his favourite son.

These were in the times when Elric left his

friend Moonglum in Tanelorn and ranged the whole world to find a land which

seemed enough like his own that he might wish to settle there, but no such land

as Melniboné could be a tenth its rival in any place the new mortals might

dwell. And all these lands were mortal now

.

He had begun to learn that he had earned a

loss which could never be assuaged and in losing the woman he loved, the nation

he had betrayed, and the only kind of honour he had known he had also lost part

of his own identity, some sense of his own purpose and reason upon the Earth

.

Ironically, it was these very losses, these

very dilemmas, which made him so unlike his Melnibonéan folk, for his people

were cruel and embraced power for its own sake, which was how they had come to

give up any softer virtues they might once have possessed, in their need to

control not only their physical world but the supernatural world. They would

have ruled the multiverse, had they any clear understanding how this might be

achieved; but even a Melnibonéan is not a god. There are some would argue they

had not produced so much as a demigod. Their glory in earthly power had brought

them to decadent ruin, as it brought down

all empires who gloried in gold or conquest or those other ambitions which can

never be satisfied but must forever be fed

.

Yet even now Melniboné might, in her

senility, live, had she not been betrayed by her own exiled emperor

.

And no matter how often Elric reminds

himself that the Bright Empire was foredoomed to her unhappy end, he knows in

his bones that it was his fierce need for vengeance, his deep love for Cymoril

(his captive cousin); his own needs, in other words, which had brought down the

towers of Imrryr and scattered her folk as hated wanderers upon the surface of the

world they had once ruled

.

It is part of his burden that Melniboné did

not fall to a principle but to blind passion …

As

Elric made to bid farewell to his temporary ally, he was attracted to something

in the countess’s wicked eye, and he bowed in assent as she asked him to ride

with her for a while; and then she suggested he might care to take wine with

her in her tent.

“I

would talk more of philosophy,” she said. “I have longed so for the company of

an intellectual equal.”

And

go with her he did, for that night and for many to come. These would be days he

remembered as the days of laughter and green hills broken by lines of gentle

cypress and poplar, on the estates of Guyë, in the Western Province of

Anakhazhan in the lovely years of her hard-won peace.

Yet

when they had both rested and both began to look to satisfy their unsleeping

intelligences, it became clear that the countess and Lord Elric had very

different needs and so Elric said his goodbyes to the countess and their

friends at Guyë and took a good, well-furnished riding horse and two sturdy

pack animals and rode on towards Elwher and the Unmapped East where he still

hoped to find the peace of an untarnished familiarity.

He

longed for the towers, sweet lullabies in stone, which stretched like guarding

fingers into Imrryr’s blazing skies; he missed the sharp wit and laughing

ferocity of his kinfolk, the ready understanding and the casual cruelty that to

him had seemed so ordinary in the time before he became a man.

No

matter that his spirit had rebelled and made him question the Bright Empire’s

every assumption of its rights to rule over the demibrutes, the human

creatures, who had spread so thoroughly across the great land masses of the

North and West that were called now “the Young Kingdoms” and dared, even with

their puny wizardries and unskilled battlers, to challenge the power of the

Sorcerer Emperors, of whom he was the last in direct line.

No

matter that he had hated so much of his people’s arrogance and unseemly pride,

their easy resort to every unjust tyranny to maintain their power.

No

matter that he had known shame—a new emotion to one of his kind. Still his

blood yearned for home and all the things he had loved or, indeed, hated, for

he had this in common with the humans amongst whom he now lived and traveled:

he would sometimes rather hold close to what was familiar and encumbering than

give it up for something new, though it offered freedom from the chains of

heritage which bound him and must eventually destroy him.

And

with this longing in him growing with his fresh loneliness, Elric took himself

in charge and increased his pace and left Guyë far behind, a fading memory,

while he pressed on in the general direction of unknown Elwher, his friend’s

homeland, which he had never seen.

He

had come in sight of a range of hills the local people dignified as The Teeth

of Shenkh, a provincial demon-god, and was following a caravan track down to a

collection of shacks surrounded by a mud-and-timber wall that had been

described to him as the great city of

Toomoo-Kag-Sanapet-of-the-Invincible-Temple, Capital of Iniquity and

Unguessed-At Wealth, when he heard a protesting cry at his back and saw a

figure tumbling head over heels down the hill towards him while overhead a

previously unseen thundercloud sent silver spears of light crashing to the

earth, causing Elric’s horses to rear and snort in untypical nervousness. Then

the world was washed with red-gold light, as if in a sudden dawn, which turned

to bruised blue and dark brown before swirling like an angry current towards

the horizon and vanishing to leave a few disturbed clouds behind them in a

drizzling and depressingly ordinary sky.

Deciding

this event was sufficiently strange to merit more than his usually brief

attention, Elric turned towards the small, red-headed individual who was

picking himself out of a ditch at the edge of the silver-green cornfield,

looking nervously up at the sky and drawing a rather threadbare coat about his

little body. The coat would not meet at the front, not because it was too tight

for him, but because the pockets, inside and out, were crammed with small

volumes. On his legs were a matching pair of trews, grey and shiny, a pair of

laced black boots which, as he lifted one knee to inspect a rent, revealed

stockings as bright as his hair. His face, adorned by an almost

diseased-looking beard, was freckled and pale, from which glared blue eyes as

sharp and busy as a bird’s, above a pointed beak which gave him the appearance

of an enormous finch, enormously serious. He drew himself up at Elric’s

approach and began to stroll casually down the hill. “D’ye think it will rain,

sir? I thought I heard a clap of thunder a moment ago. It set me off my

balance.” He paused, then cast a look backward up the track. “I thought I had a

pot of ale in my hand.” He scratched his wild head. “Come to think of it, I was

sitting on a bench outside The Green Man. Hold hard, sir, ye’re an unlikely

cove to be abroad on Putney Common.” Whereupon he sat down suddenly on a grassy

hummock. “Good lord! Am I transported yet again?” He appeared to recognize

Elric. “I think we’ve met, sir, somewhere. Or were you merely a subject?”