Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made (5 page)

Read Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made Online

Authors: Andy Hertzfeld

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General, #Industries, #Computers & Information Technology, #Workplace Culture, #Research & Development, #Computers, #Operating Systems, #Macintosh, #Hardware

The boot ROM allowed us to download other programs from the Lisa to the Mac over a serial line, to try out new code and test or demo the prototype. There was a ton of work to do: writing an operating system, hooking up the keyboard and mouse, getting Bill's graphics and UI routines running, and many other tasks, but we also sometimes just did things for fun.

In early March of 1981, I wrote a fast, disk-based slideshow for the Mac the same night that I got the disk routines going (see

nybbles

). It was exciting to see detailed, relatively high resolution images parading across the display so quickly.

By April, I was experimenting with writing custom graphics routines, to show off the raw graphical horsepower of the system. I had written a few ball-bouncing routines on the Apple II, and I thought it would be interesting to see how many balls could the Mac animate smoothly. I wrote some 68000 code to draw 16 by 16 images very quickly, and I found that I could keep more than one hundred balls animating smoothly, which seemed pretty impressive. I also wrote a small sketch program with a seed fill using Bill Atkinson's 8 by 8 pattern bitmaps, as well as an entertaining Breakout game, where I implemented Bud's idea of having to dodge the bricks when they fell down after you hit them.

Bob Bishop had experimented with a variety of graphical special effects on the Apple II, so I thought I'd try some of them out on the Mac. The idea was to transfer an image onto the screen in an entertaining way. The one that I liked best was a kind of waterfall effect, where you copied an image onto the screen using a varying number of multiple copies of successive scan lines, stretching the image vertically. The image looked like it poured onto the screen like water going over a waterfall; it somehow was rather hypnotic. I often used it with an image of the Muppets I converted from the Apple II, and the "Stretching Muppets" demo became pretty well known.

In May 1981, Bud stayed up all night and ported QuickDraw and some pull-down menu code from the Lisa to the Mac (see

busy being born, part 2

). For the first time, we were running mouse-based software with real pull-down menus. The best part of the demo was the pattern menu, which showed off the extensibility of the menu routines to draw an entirely graphical menu.

In June 1981, we realized that it would be worthwhile to create a stand-alone demo environment, where the Macintosh booted and ran programs from its own disk, even though we'd only use it temporarily. Our own operating system wasn't close to usable yet, but Rich Page had written a simple operating system called the "Lisa Monitor" which was based on UCSD Pascal, that was pretty easy to port - all we had to do was integrate our I/O drivers. Soon, using the Monitor, a Mac could boot up and run demos without help from a Lisa.

In the Lisa Monitor environment, it was easy for us to run QuickDraw-based programs. Soon, we had a Window Manager demo, featuring balls bouncing in multiple windows (see

bouncing pepsis

), as well as a nice icon editor and MacSketch, an early ancestor of MacPaint going.

I think the most interesting early demo was an early prototype for the Finder, written by Bruce Horn and myself in the spring of 1982, and pictured above. Its window was filled with an image of a floppy disc, over which the files were represented as draggable tabs. You could select files and perform operations on them by selecting them and then clicking on command button. Bruce also made a second mock-up, with folder icons, which influenced Bill's design for Lisa's Filer (see

rosing's rascals

), which we eventually adopted instead. It provides an interesting glimpse of possibilities that we might have chosen instead of what seems so familiar today.

Bicycle

by Andy Hertzfeld in April 1981

Logo for Mac University Consortium

Jef Raskin chose the name "Macintosh", after his favorite kind of apple, so when Jef was forced to go on an extended leave of absence in February 1981, Steve Jobs and Rod Holt decided to change the name of the project, partially to distance it from Jef. They considered "Macintosh" to be a code name anyway, and didn't want us to get too attached to it.

Apple had recently taken out a two page ad in Scientific American, featuring quotes from Steve Jobs about the wonders of personal computers. The ad explained how humans were not as fast runners as many other species, but a human on a bicycle beat them all. Personal computers were "bicycles for the mind."

A month or so after Jef's departure, Rod Holt announced to the small design team that the new code name for the project was "Bicycle", and that we should change all references to "Macintosh" to "Bicycle". When we objected, thinking "Bicycle" was a silly name, Rod thought that it shouldn't matter, "since it was only a code name".

Rod's edict was never obeyed. Somehow, Macintosh just seemed right. It was already ingrained with the team, and the "Bicycle" name seemed forced and inappropriate, so no one but Rod ever called it "Bicycle". For a few weeks, Rod would reprimand anyone who called it "Macintosh" in his presence, but the new name never acquired any momentum. Finally, around a month after his original order, after someone called it "Macintosh" again, he threw up his hands in exasperation and told us, "I give up! You can call it Macintosh if you want. It's only a code name, anyway."

But it was a code name that proved to be sturdy and resilient. In the Fall of 1982, Apple paid tens of thousands of dollars to a marketing consulting firm to come up with a themed set of names for Lisa and Macintosh. They came up with lots of ideas, including calling the Mac the "Apple 40" or the "Apple Allegro". After hearing all the suggestions, Steve and the marketing team decided to go with Lisa and Macintosh as the official names. They did manage to reverse engineer an acronym for Lisa, "Local Integrated Systems Architecture", but internally we preferred the recursive "Lisa: Invented Stupid Acronym", or something like that. Macintosh seemed to be acroynm proof.

But there was still a final hurdle to clear - the name was too close to a trademark from the McIntosh stereo company. I'm not sure how the situation was resolved (I suspect that Apple paid them a modest amount), but toward the end of the retreat in January 1983, Steve announced to the team that we had gotten rights to use the name. He dashed a champagne bottle against one of the prototypes, and declared, "I christen thee Macintosh!"

A Message For Adam

by Andy Hertzfeld in April 1981

The Osborne 1 portable computer

The Apple II was officially introduced at the First West Coast Computer Faire in April 1977, one of the very first trade shows dedicated to the newly emerging microcomputing industry. I loved the Computer Faires because they were attended by passionate hobbyists in the days before commercial forces completely dominated.

In April 1981, a few members of the Mac team took off the afternoon and drove up to San Francisco to visit the seventh West Coast Computer Faire at Brooks Hall. The biggest splash at the show was the unveiling of the Osborne I, from a brand new company named Osborne Computer, which was touted as the world's first portable computer.

The Osborne I was the brain-child of Adam Osborne, who was a well known figure in the world of early microcomputers. Adam was a technical writer who founded a publishing company to publish crucial information about microprocessors and software that was sorely lacking at the time, which was eventually sold to McGraw-Hill. He became a controversial columnist, opining on the industry from his pulpit in InfoWorld and other publications. He had a populist vision of computing, touting a no-frills, low cost, high volume approach to the business.

In 1980, he decided to put his theories into practice, and founded the Osborne Computer Company to design, manufacture and market the Osborne 1, which was a low cost, one-piece, portable computer complete with a suite of bundled applications. He recruited Lee Felsenstein, already a microcomputing legend as the master of ceremonies of the Home Brew Computer Club, to design the hardware. Now, they were introducing the fruits of their labor at the West Coast Computer Faire, as Apple had done four years earlier.

The Osborne 1 was on display at their crowded booth near the center of Brooks Hall. It looked a lot like an oversized lunch box, with a keyboard on the back of the lid, crammed full with two floppy drives and a tiny, 5 inch monitor in its center. We were a little surprised, because it looked uncannily like some of Jef Raskin's early sketches for the Macintosh, which Steve had recently abandoned for a vertically oriented design. Portable was sort of a euphemism as the thing weighed around 25 pounds, but at least it fit under an airline seat, barely. As Macintosh elitists, we were suitably grossed out by the character-based CP/M applications, of course, which seemed especially clumsy on the tiny, scrolling screen.

We worked our way up to the front of the crowd to get a good look at the units that were on display. We started to ask one of the presenters a technical question, when we were suprised to see Adam Osborne himself standing a few feet from us, looking at our show badges, preempting the response.

"Oh, some Apple folks", he addressed us in a condescending tone, "What do you think? The Osborne 1 is going to outsell the Apple II by a factor of 10, don't you think so? What part of Apple do you work in?"

When we told him that we were on the Mac team, he started to chuckle. "The Macintosh, I heard about that. When are we going to get to see it? Well, go back and tell Steve Jobs that the Osborne 1 is going to outsell the Apple II and the Macintosh combined!"

So, after returning to Cupertino later that afternoon, we told Steve about our encounter with Adam Osborne. He smiled, with a sort of mock anger, and immediately grabbed the telephone on the spare desk in Bud's office, and called information for the number of the Osborne Computer Corporation. He dialed the number, but it was answered by a secretary.

"Hi, this is Steve Jobs. I'd like to speak with Adam Osborne."

The secretary informed Steve that Mr. Osborne was not available, and would not be back in the office until tomorrow morning. She asked Steve if he would like to leave a message.

"Yes", Steve replied. He paused for a second. "Here's my message. Tell Adam he's an asshole."

There was a long delay, as the secretary tried to figure out how to respond. Steve continued, "One more thing. I hear that Adam's curious about the Macintosh. Tell him that the Macintosh is so good that he's probably going to buy a few for his children even though it put his company out of business!"

Square Dots

by Andy Hertzfeld in April 1981

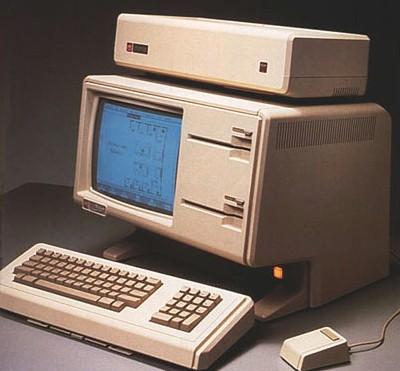

The Apple Lisa

From the very beginning, even before it had a mouse, the Lisa was designed to be an office machine, and word processing was considered to be its most important application. In the late seventies, the acid test for an office computer (as compared with a hobby computer) was the ability to display 80 columns of text.