Rickles' Book (16 page)

Authors: Don Rickles and David Ritz

A

s a kid growing up in New York, I loved the Giants. When I moved to L.A, though, I switched loyalties to the Dodgers.

For over forty years now, I’ve been bleeding Dodger blue.

I’ve suffered and celebrated with the Dodgers during the Koufax-Drysdale sixties, the Garvey-Cey seventies, the Valenzuela-Hershiser eighties and the Piazza-Karros nineties. I follow every catch, every pitch, every play.

I even became pals with manager Tommy Lasorda.

Lasorda loves Hollywood as much as Hollywood loves him. He was close to Sinatra, another big Dodger fan, and had an open-door policy when it came to celebrities.

After the game, he liked having people in his office. If the Dodgers won that day, his office became an Italian restaurant and Tommy held court. If the Dodgers lost, he still held court. Either way, if you hung out with Tommy you’d never go hungry.

On one Fan Appreciation Day, Tommy invited me into his office while the team was on the field during batting practice. It was the last game of the season, and since the Dodgers were out of contention, it didn’t mean anything.

“Don,” said Tommy, “put on a uniform.”

“Are you kidding?” I asked.

“No, I’m not kidding. You always wanted to be a Dodger. Well, here’s your chance, buddy. We’re about the same size, and I’ve got an extra. Go ahead, put it on and sit next to me. You’ll love watching the game from the dugout.”

I did. I was like a little kid. I loved sitting next to the guys and getting the players’ point of view. It was a real kick in the head.

In the sixth inning, the Dodger pitcher got shelled.

“Go take him out, Don.”

“What!”

“You heard me, go give him the hook. Yank him out and give the bullpen the signal for the southpaw.”

Why the hell not!

It was a fantasy come true. I trotted out to the mound.

“Sorry, fella,” I told the pitcher, “you’re through.”

“You’re not the manager,” he shot back. “You’re not even a coach. You can’t pull me out of the game.”

“Give me the ball,” I demanded.

“You’re crazy,” he said.

Meanwhile, homeplate umpire Harry Wendelstedt, a great veteran, headed out to the mound.

“What’s going on here?” he asked.

When he got in my face, he saw who it was and said, “I’ll be damned! Don Rickles! Don, any chance of getting me two tickets to see Dean Martin in Vegas?”

O

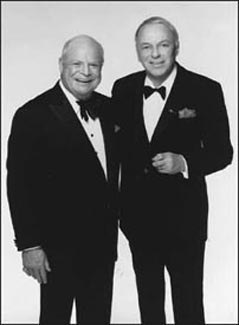

ne of the biggest honors of my life was when Frank Sinatra asked me to open for him during his final concert tours in the mid-nineties.

By then, I had long established a policy not to open for anyone. For Frank, though, I not only broke my policy, but I did so gratefully. I knew this was going to be show-business history. Touring with Sinatra—along with Frank, Jr., who was leading the orchestra—was something I wouldn’t miss for the world.

By then, Frank was starting to have problems. But that doesn’t mean he had lost his charm or his ability to thrill his fans. He had that until the end.

“Anything you particularly want me to do with my opening routine?” I asked him.

“Hey, Rickles,” he said, “just enjoy yourself.”

“Great,” I said.

“Frank begged me to open for him,” I announced as soon as I hit the stage. “A real mercy mission.”

Our last hurrah together.

Equal billing, but Frank got $2 billion more than me.

When Frank hit the stage, he invited me back on. We did a bit where I’d come out and give him a drink.

“Thanks, Don,” he’d say. “What’s up?”

“Well, Frank, your close friend Vinnie Gallamano got two in the head. And Salvatore Boomboz got hit by a truck.”

Frank broke up. Then we drank, both of us saying, “

A salut’

.”

One night when I went out there, though, Frank’s memory was playing tricks on him.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

“I’m here to bring you a drink, Frank.”

“I’ve got a drink.”

“Look, Frank,” I said, going into the routine, “Sal Maganazzo got whacked by Vinnie Luccalazzi—”

“I don’t care,” said Frank.

“But Frank—”

“Leave.”

Suddenly, I was covered with flop sweat.

“Do me a favor, Don. Get lost.”

I hurried off the stage. The funny thing was that the audience thought it was funny. They howled. They were sure it was part of the act.

I wasn’t sure what it was.

Before the show, my dressing room was filled with important, well-connected guys who wanted to say hello to Frank, but Frank’s door was closed.

“What do you think, Don? Should we knock on his door?” they’d ask me.

“What do I know? Knock on the door,” I said. “But I’m not knocking.”

Before our New York opening, one of the guys came to my dressing room. He was a big man, and he was wearing a bright yellow suit. He looked like he’d just fallen into a tub of butter.

“Look, Don,” he said. “I’m your biggest fan. And I’m Frank’s biggest fan. But do me a favor, don’t draw any attention to me. I like to play it low-key. These days I need to keep a low profile.”

When I came on stage, I saw him seated—in the front row yet. With his yellow suit, who could miss him?

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said, “I’ve played everywhere. But this is the first time,” I added, pointing to the man in the yellow suit, “that I’ve ever played before a two-hundred-fifty-pound parakeet.”

The big guy laughed, so his boys joined in.

Lucky me. I got to keep breathing.

“Frank, Vinnie just got two shots in the head.”

After the tour, Frank struggled.

I’d go and visit him. We’d sit and watch a little television. At times when I noticed that Frank had lost that twinkle in his eyes, I knew it was time for Rickles to try to make him laugh.

May 1998.

I’m sitting in the Church of the Good Shepherd in Beverly Hills. I’m a pallbearer at Frank’s funeral.

I think back a hundred years ago when he first came to see me in Miami Beach. I think of his generosity, his crazy humor, his fierce loyalty. I hear his voice, the greatest singing voice in the history of singing, a voice loved by people the world over.

At the end of the service, I walk up and stand in front of his coffin.

A priest gently points out that I’m leaning on the coffin.

“Oh, that’s okay, Father,” I say. “Frank wouldn’t mind. I leaned on him my whole life.”

We laid him to rest that afternoon.

Now when I’m relaxing with an iPod in my ears, I love listening to Frank. Frank’s not going anywhere. His talent is forever.

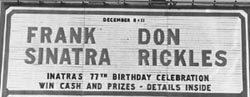

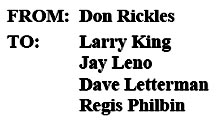

SUBJECT:

Selling Book

Now that this book’s almost finished, I have to think about promoting it. I wonder if any of you guys could help me out?

Jay Leno:

He’s a wonderful man, especially if your car needs a lube job. If he invites you to dinner, it’s cheeseburgers in his garage. Jokes aside, Jay has a magnificent car collection.

Jay also has a great marriage and a great wife, Mavis. They’re very compatible. She likes to travel, he likes to stay home and spit-shine his Chevys.

Jay has a big heart. When Johnny Carson died, he invited me and Newhart on his show to give a tribute. We had many beautiful memories of our dear friend, and Jay provided us with a national audience to pay respects to his predecessor.

Thanks, Jay, now what about my book?

Dave Letterman:

Funny guy.

Extrovert onstage, introvert offstage. Offstage he hides behind a baseball cap. Once, he came to my dressing room in Vegas. My dear friends Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme dropped by to wish me well, giving me many kisses and big hugs. The big emotions got Dave so nervous he ran out in the hall and hid.

When I’d appear on his show, I’d always kid him, “Dave, why don’t we ever have dinner together?”

He’d laugh it off.

One night, though, when the show ended, his producer said, “Meet Dave at ‘21.’ ”

When Barbara and I got to “21,” the maitre d’ greeted us and led us down a flight of stairs. We found ourselves in the wine cellar. Dave was there with his full staff and a beautifully festive table. It was a great evening.

Before leaving, I took Dave aside, thanked him and then asked, “What about my book?”

Regis Philbin:

For many years, people have asked me, “What’s Regis’ talent?”

For many years, I’ve answered, “He believes it’s singing.”

The TV host and his idol.

Seriously, though, Regis is terrific. We’ve been friends for nearly fifty years. The man can talk. He can sing. He can tell a joke. Mostly, though, he screams.

In the old days, we’d walk down Hollywood Boulevard and Regis would scream, “I’ve got Rickles here! Say hello to Rickles!”

Even today Regis still screams. When it comes to promoting Rickles, he’s unrelenting.

Regis has never been shy in creating fans. He’d interrupt robbers during a bank holdup to ask, “Hey guys, do you ever catch me on television?”

We’ve worked together in theaters where Regis would come to my dressing room before the show like he was shot out of a canon. “We’re going to knock ’em dead tonight, Don!” he’d scream. “They’re going to love us!”

King finally meets a world leader.

He got me so worked up I’d do my finish before I started.

But I love the guy. Everyone does.

Now, Regis, what about my book?

Larry King:

I already told you stories about King back in Miami when we were both getting started.

Over the years, of course, Larry has gotten famous and very influential.

Here’s what I like about Larry:

He interviews the Prime Minister of England or the French ambassador to the United Nations. Serious people, serious questions. He’s getting to the bottom of some world crisis, and he does it with pinpoint clarity and total confidence.

Then, an hour later, after the broadcast, he’s a different guy. We go to a deli where he says, “Should I have the corned beef lean or the pastrami thin without the cole slaw?” The man has a nervous breakdown over what to order.

“If you can decide what to ask the President of the United States,” I say, “why can’t you decide between pumpernickel and rye?”

“Maybe I’m better off with a scooped-out bagel and no butter,” says Larry. “And maybe a little cottage cheese. That can’t hurt me, can it, Don?”

“Larry, stop planning on living forever. Everyone’s going to end up in a big talk show in the sky. But in the meantime, while you’re here, what about my book?”

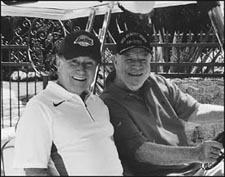

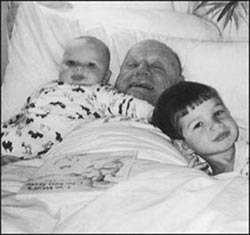

Pop-Pop holds court with grandsons, Harrison and Ethan.