Rickles' Book (6 page)

Authors: Don Rickles and David Ritz

T

he winter sun is warm. Palm trees sway in the breeze. Unemployed actors chat it up at Schwab’s on Sunset Boulevard. If you’re lucky, you spot George Burns and Gracie Allen shopping for clothes at Bullock’s over on Wilshire Boulevard. Oranges are budding in the Valley, birds are chirping in Beverly Hills and the blue sky is smog-free. The fifties in L.A. is a beautiful time.

At the corner of Hollywood and Vine, in the heart of the entertainment district, you can’t help but notice Zardi’s Jazzland. That’s where all the big names play—Ella, Ellington, Basie, and Brubeck.

Will Osborne’s big band wasn’t exactly the biggest name in jazz, but Will played Zardi’s, too, and Joe Scandore, bless his heart, got me on the bill. That was my ticket to California.

Hello, La-La Land.

Hollywood was exciting because you never knew who might show up. Like everyone else, I was looking for stars. Unlike everyone else, I wasn’t looking for their autographs; I was looking to rib them.

But if the stars came to Zardi’s, they must have come in disguise, because I didn’t recognize anyone. It was a jazz-loving crowd. The comic was about as important as the free matchbooks on the table. He was disposable. No matter, I had made it to Hollywood and Hollywood is where dreams come true.

From Zardi’s, I went to the Interlude, an upstairs room on the Strip where I continued to look for stars. The closest I got was Richard Burton. He must have gotten there by accident. He had no earthly idea that I was on stage. The guy was in a spaceship headed for the moon.

Downstairs from the Interlude was the big showroom, the Crescendo. That’s where Mort Sahl, newspaper in hand, held court. Mort made fun of current politics better than anyone. His hip style was all the rage.

I didn’t think of myself as hip, but you couldn’t call me square. I was irreverent. Some even said I was unrelenting. But unlike Mort, my audience was still pretty limited.

How was I ever going to break out?

Would cold-blooded Hollywood ever accept this earnest warmhearted young man from Jackson Heights?

Stay tuned.

I

t didn’t start out like a big break at all.

Most places in Hollywood would give you at least a closet-sized dressing room. This place had no dressing room and no shower. I’m a shower fanatic. I sweat like crazy; in between shows I have to get clean. But here I could only do that by slipping into an alley where a couple of guys held up towels to protect my modesty while a third guy poured water over my head.

I’m talking about the Slate Brothers, a nightclub on La Cienega Boulevard on the eastern fringe of Beverly Hills.

I got there by a fluke.

Remember I mentioned Sally Marr, the sweet stripper and mother of Lenny Bruce? Well, Lenny, now a budding star, was playing the Slate Brothers when the owners took offense at his language. I don’t know the details, but they considered Lenny, who others recognized as brilliant, too offensive for their audience. Now here’s the funny part: They hired me, Mr. Good Taste, to replace Lenny Bruce.

“They” were the Slate brothers, actual siblings and former song-and-dance men from the movies, who owned the club and named it after themselves.

There were three Slates—Sid, Jack and Henry.

Henry was the power. He was shot out of a cannon. He was a character straight out of

Guys and Dolls

, a Jewish guy with an Irish face. With the men in the back room, he cursed enough to make Lenny Bruce blush. With the women, he was smooth as silk. Henry liked to drink and loved to laugh. The man took a shine to me from the start.

Like Willie Weber and Joe Scandore, Henry went out of his way to push me on the public. I didn’t know that this push would be the big one—the one I’d been waiting for.

Picture it: On Monday, I’m on stage. There’s Elizabeth Taylor staring up at me.

“Elizabeth,” I say, “you gotta stop calling me. I’m going with someone.”

It’s Tuesday, and there’s Jack Benny.

“Jack, does Burns know you’re staying up late?”

Wednesday comes along and here’s Judy Garland.

“Judy, find Mickey Rooney. I’ll throw straw on the floor, and you guys can do a show here in the barn.”

Thursday I get a glimpse of Martha Raye.

“Hi, Martha, close your mouth. You’re sucking up the air-conditioning.”

The weekends are nuts. Everyone shows up on the weekends.

Jimmy Durante: “Take off your hat, Jimmy. It’s not a Jewish holiday.”

Gene Kelly: “Enough with the rain. I’ll buy you an umbrella.”

Red Skelton: “Get your face fixed.”

Bob Hope: “Don’t worry. I’ll get you work at the USO.”

Donald O’Connor: “Stop dancing on the walls and try the floor.”

Milton Berle: “I didn’t recognize you dressed up as a guy.”

Clark Gable: “Forget Spencer Tracy. You and I would be great.”

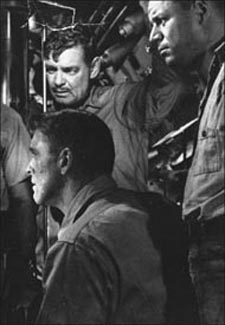

Rickles carrying the big stars, Lancaster and Gable, in

Run Silent, Run Deep.

N

ext thing I know, Henry Slate is driving me to some soundstage in Hollywood. Slate’s not my manager, but he’s acting like he is. That’s fine with me. I’m tense and don’t mind the company. Apparently, Robert Wise, a big-time director, wants to audition me for the new Clark Gable movie,

Run Silent, Run Deep

, that costars Burt Lancaster, who’s also the producer. They say it’s a submarine thriller. As a Navy man, I’m perfect for the role. As an insecure newcomer to Hollywood, I’m a nervous wreck.

We walk into a soundstage the size of an airplane hangar. I’m feeling as big as a Planters peanut. The place is pitch-dark except for a work light in the middle of a stage. This isn’t an audition; this is a bad dream.

I might as well be on the moon. I’m holding the script, my hands are shaking and there’s barely enough light to see the words. I ask if Mr. Gable is present. Mr. Wise doesn’t answer me. All he says is, “Please read the lines.”

I’m a seaman on the bridge with the captain. The captain is Gable.

“The boat’s in trouble, sir,” I say. “Should we fire the guns?”

The captain is supposed to reply, but where’s the captain?

Suddenly, out of nowhere, a booming voice bounces off the walls and hits me in the face: “TAKE IT DOWN…DIVE, DIVE, DIVE!”

The voice belongs to Clark Gable. I can’t believe it. My dialogue disintegrates into “Blah-blah-blah.” I look into the darkness but don’t see Gable. I just hear his voice. I’m confused and excited. Where the hell is he? I’m completely out of whack. Is Gable really talking to me?

“Did you hear my orders, seaman?” asks the disembodied Gable.

Again, I go into “Blah-blah-blah.”

Wise stops me and says, “Take it easy, son. Just look at the script and say your lines.”

Somehow I do it. And get back into the rhythm of the dialogue.

Next thing I know, Wise is saying, “Good, Rickles, we want you for this role.”

I’m still wondering how all those Blah-blah-blahs got me the part.

Another week passes before I actually meet Gable face-to-face. Before that, Burt Lancaster, a serious man, says to me, “This is a serious movie, Don. You really need to know about submarines. It will help you in your character development if you know the intricate workings of the submarine.”

Burt says all this as if we’re about to be ordered to our battle stations.

Meanwhile, Gable is one of the most relaxed movie stars in the history of the business.

“Look,” he tells me, “I’m a five o’clock guy.”

“What does that mean, Mr. Gable?” I ask.

“It means, kid, that my day ends at five. Regardless. Five is scotch-and-soda time. And then I’m on my way home.”

Every day at five, Gable sticks to his guns. Five o’clock comes and he’s in the trailer. He enters as a Navy commander and exits as a Brooks Brothers model. Driving off the lot in his Bentley convertible, he waves goodbye as he passes through the security gates.

Because he’s a producer of the picture, Lancaster is far more intense and worries about overages.

Back in those days, most of the action isn’t done on location but is manufactured right there in the studio, smoke-and-mirror style. One scene involves a series of explosions followed by a deluge of water. The mechanics are tricky and the technical guys work on it all day. They can’t quite get it right. Finally, at about five to five, it all comes together—the bombastic explosions and a deluge of water. Gable and I are in the battle scene, the climax of the film. Robert Wise signals action and all hell breaks loose. The special effects are spectacular.

In the midst of this drama, Gable says, “Sorry, boys, Mr. Five O’Clock is done for the day.”

And then, with all the grace of a European prince, Gable struts to his trailer.

Lancaster chases after him.

“Clark,” says Burt, “we finally got this thing to work. It’ll cost a fortune if we dismantle it. We gotta film it now!”

Ever the gentleman, Gable looks at Lancaster sympathetically. “Relax, Burt,” he says. “I’ll dive with the submarine tomorrow.”

My nervous-seaman portrayal turned out to be realistic. I was afraid I’d forget my lines, so I hid them under my pillow in the submarine bunk so I could keep stealing peeks.

The seaman character was scared of getting blown up; I was scared of drawing a blank. It amounted to the same thing.

The movie came out and proved to be a hit. Everyone loved Gable’s performance. Lancaster was sensational. Rickles was largely ignored, but I’d made it to the big screen. Big things were happening. I thought that Hollywood was mine.

That’s the kind of dummy I was.

E

tta came out to the Coast. She wouldn’t have missed it for the world. Her sonny boy had made a movie and was gaining a reputation. My mother wanted to be close to the action and, as always, I was glad to have her strong support.

In spite of having steady work, I shared an apartment with Mom not far from the Slate Brothers club, where I was still performing six nights a week. Our place was so small that we hung a curtain that separated Mom’s living quarters from mine. It was tight, but we made due. The only problem involved dating. How do you say, “Mom, I love you very much, but do you mind not coming back till four o’ clock in the morning?”

Mom became a regular at the Slate Brothers. She laughed harder than anyone, but when I got offstage, she’d say, “Don, dear, do you have to make fun of people? Why can’t you make nice, like Alan King?”

Golfing with Uncle Miltie.

“That’s my act, Mom,” I’d say. “That’s what’s getting me over.”

“Just go easy with the big stars,” she’d advise. “Don’t get the big stars upset.”

One night, after the last show, I saw Etta talking to the bartender, a handsome black man with natural charm and class. His name was Harry Goins. Harry was one in a million. How many guys would volunteer to shop at Canter’s for all the Jewish delicacies Mom loved and then ask if I needed help with my wardrobe? Harry couldn’t do enough for us.

One day Mom just came out and said it. “Ask Harry if he’d be willing to work for us. He’s a gem. Hire Harry and, if we’re lucky, he’ll be with us forever.”

Etta was right. For the next forty years, Harry Goins was by my side. He was the brother I never had.

When Mom and I got a slightly bigger apartment at the Park Sunset, the always-immaculate, always-

well-spoken Harry helped arrange her pool parties. Harry would lay out the food in an artful manner, displaying Etta’s chopped liver like it was Beluga caviar.

Meanwhile, Etta rounded up guests. I don’t know how she did it, but she got the stars to attend. Everyone from Kirk Douglas to Debbie Reynolds to Jack Carter and the Ritz Brothers would show up. Even Sinatra dropped by. I remember one night when Milton Berle sat in a lounge chair next to Mom.

“I first saw Don in Florida,” Milton told Etta. “I said back then that your son had a great style. Mine.”