Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw (2 page)

Read Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw Online

Authors: Norman Davies

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #War, #History

Of course, many people are likely to have heard of a ‘rising’ or of an ‘uprising’ in Warsaw. They may have read books, watched films, or listened to survivors’ accounts. And they may well be under the impression that the event has been fully aired and discussed. If so, they will not have to explore very far to realize that much of the existing information in these matters is highly selective and misleading.

It may be of some help to point out that the Underground fighters who launched ‘the Warsaw Rising’ did not themselves use the term. For reasons connected with developments on the Eastern Front, they called it ‘the Battle for Warsaw’. It was only after the city had been destroyed, and especially after the war, that ‘the Warsaw Rising’ or ‘Uprising’ came to be widely used, but by different people for different purposes.

Warsaw was, and is, the capital of a country whose most important alliance in 1944 was with Great Britain. Politically, this alliance put the country’s exiled government firmly in the camp of liberal democracies led by Britain and USA. In an old-fashioned world, where the ‘Great Powers’ alone attended the top table and would decide things among themselves on behalf of less powerful clients, it also meant that the Anglo-Americans had assumed a degree of responsibility for their ally. Geographically, however, Warsaw lay plumb in the middle of Europe, immediately adjacent to the two largest combatant powers – that is, to Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. As a result, the Rising inevitably erupted in the very cockpit of European conflict. Not only did it take place close to the front of the titanic German–Soviet War. It was embroiled at a sensitive interface of the three-sided arena where Western Democracy confronted Fascism on the one hand and Stalinist Communism on the other. It was no local skirmish.

The difficulties of explaining these matters are legion. The particulars of Central European history are not widely studied outside Central Europe; and the valiant contributions of lesser members of the Allied coalition of 1939–45 are largely forgotten. In history-writing, as in contemporary politics, countries which were once in the Allied camp but which later found themselves in different company have been obliged to wage an uphill battle. Their interests have often been eclipsed by publicists working for more vocal or more favoured competitors. For this reason, in constructing a narrative about the Warsaw Rising, it was essential to locate Warsaw firmly within the Allied, German, and Soviet strands of the war, and only to move on to the Rising after the complicated setting had been fully expounded.

Since the Western Powers enjoyed a clear-cut victory over Germany in their part of Europe, Western readers invariably make a clear-cut mental distinction between the wartime and the post-war years. In Russia too, where the victory of 1945 has remained a sacred memory, the time before and after ‘Liberation’ is presented as the difference between night and day. But in many countries of Central Europe, where one totalitarian occupation was succeeded by another, the significance of VE-Day is greatly reduced. Indeed, the very idea of ‘Liberation’, and of a clear break with conflict and suffering, was often considered a bad joke. Hence, it would have been unjust to close the story of the Varsovian insurgents at the end of the Rising or at the end of the war in May 1945, and to pretend that the survivors lived happily ever after. Instead, it seemed absolutely vital to trace the fate of the insurgents, and of their vilified reputation, into the post-war world.

The sources for a study of the Warsaw Rising are immense. I have encountered a score of general works on the topic; each with its special slant, and each with its special weaknesses. The catalogue of the Bodleian Library lists seventy-five titles. There are negative interpretations, and positive accounts; but few which approach all the participants with equal scepticism.

1

There is also a huge mass of specialized literature that deals with everything from diplomatic and military aspects to the design of barricades, the organization of the underground security services, or the adventures of individual units. And there is a large body of memoirs and diaries, both published and unpublished. Since the collapse of the Communist regime in 1990, veterans have been free to print their own journals, notably the monthly

Biuletyn Informacyjny

; and a great deal of work has been put into compilations of documents, chronicles, and encyclopaedias.

2

Archival sources are more problematical. For many years, the only systematic publication of relevant documents was undertaken abroad, particularly at the Polish Institute and the Underground Study Trust (SPP) in London. Much could also be found on the diplomatic and military front in the Public Record Office, the Imperial War Museum, the National Archives in Washington, or in the

Bundesarchiv

in Bonn. Yet many key collections have remained closed, or are, at best, half-open. The British intelligence archives, for instance, which will someday reveal numerous insights into the affairs of 1944, were still 95 per cent unavailable at the turn of the century. The records of the post-war Polish security services, which are vital to an understanding of Stalinist repressions, are being released only slowly. Worst of all, after a brief promise of more liberal policies, the ex-Soviet archives in Moscow are still not fully accessible. A small number of selected documents were published in the 1990s. And determined foreign researchers with local assistance can gain limited access to some collections. But by the start of the twenty-first century, the main documents relating to Stalin’s decisions in 1944 had still not been placed in the public domain. For this reason alone, I have no doubt that the definitive academic study of the Warsaw Rising still awaits its author.

As I have written on several occasions, historians inevitably form part of their own histories. And the times in which historians write, unavoidably influence what is written. In this regard, the history of an Allied coalition, which failed to live up to its obligations, may not be entirely unconnected to the present time.

Most people think of a good history book, as they think of a good novel, in linear terms. The readers start at the beginning, where they are pointed in a certain direction. They then plunge into a journey – through the jungle, up the mountain, along the road, or wherever – admiring the passing landscape, enjoying the adventures and surprises, but always heading unswervingly towards the chosen goal. At some point, better sooner than later, they reach the central drama of the story – the divorce of Henry VIII, the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, the encirclement of the German army before Stalingrad, or whatever – and they then move on to the denouement. It is a very satisfying intellectual experience.

At some point, however, I realized that the linear model is not the only design which may be followed to good effect. Different types of subject matter demand different types of treatment. In

Heart of Europe

, for instance, which was relating the memories of the past to the problems of the present, I decided that the story was best told in reverse chronological order.

3

Sometime later, when faced with the enormous task of writing ‘The Oxford History of Europe’, I again decided that radical measures had to be taken.

Europe: a history

(1996) was written on three levels simultaneously. The main text consisted, indeed, of a linear narrative. It proceeded in twelve giant strides across Europe’s past from prehistory to the late twentieth century. But each of the chapters was enhanced both by ‘Snapshots’ and by ‘Capsules’. The ‘Snapshots’, which were mini-chapters in themselves, treated a series of key moments, giving the reader a more detailed view of life and issues in a particular age. The three hundred ‘Capsules’ scattered through the text in discrete boxes touched on an array of highly eccentric and exotic topics, which contrasted sharply with the generalizations of the surrounding chapters and created an illusion of comprehensive coverage.

4

To my great relief, I found that this relatively complicated structure did not repel the readers. On the contrary, it gave them the opportunity of navigating their individual ways through the huge maze which is European history, of taking a change and a rest at numerous points in the long journey, and of dawdling and dipping whenever they wished to do so.

Faced with

Rising ’44

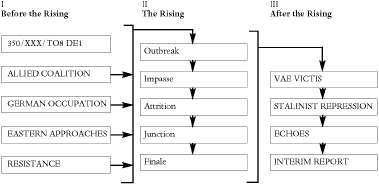

, therefore, I decided yet again that the conventional linear approach was not suitable. The subject matter was unfamiliar to English-language readers; and a series of solid introductory chapters was unavoidable. As a result, the first part, ‘Before the Rising’, would be bulkier than one might have wished; and the reader’s pace would be under threat. The solution was to start with a dramatic Prologue, and then to write four linear chapters in parallel, each presenting a different route towards the outbreak of the Rising on 1 August 1944. The readers may follow each of these routes in turn if they wish, absorbing the narrative and the informational passages as they meet them.

The Rising itself was always going to constitute the main focus of the story. Yet here I had to solve another problem. Having interviewed a large number of participants and survivors, and read numerous personal accounts, I had gained possession of a mass of fascinating memoir material, which was necessarily subjective and anecdotal but which nonetheless threw true and telling light on the human ordeals with which the story abounded. It would have been possible to weave parts of this material into the main text. But remembering the precedent of

Europe: a history

, I decided to keep it separate, and to place it in a series of eyewitness ‘capsules’, each presenting one person’s view of a particular episode. These capsules may be read alongside and in conjunction with my own historian’s narrative; or they may be picked from the tree at random as the tastebuds dictate.

The last part of the book, ‘After the Rising’, contains three chronological chapters, taking the reader from 1944 to the present. I am happy to say that each of them is written in standard linear fashion. They are rounded off by a concluding Interim Report:

From hard experience, I know that foreign names and places can create havoc in the psyche of English-speaking readers. Indeed, in the case of some languages like Polish, I believe they constitute a near insurmountable barrier to a full understanding of the country’s affairs. For it is not just a problem of unfamiliarity. It is unfamiliarity compounded by an incomprehensible system of orthography and by unique, jaw-breaking combinations of consonants and syllables that are uniquely disturbing. Charles Dickens, who met a number of Polish émigrés in London after the Rising of 1863, had a wonderful ear for this problem: ‘A gentleman called on me this morning,’ he once remarked, ‘with two thirds of all the English consonants in his name, and none of the vowels.’

5

The joke is that God created Polish by dropping his Scrabble box. But this is not just a laughing matter. If readers cannot retain the names in a narrative, they cannot follow the plot. And if they cannot follow the plot, they cannot be expected to analyse or to understand it.

6

At all events, I have decided to conduct an experiment. Wherever possible I have refrained from using foreign names altogether. I have referred to people’s positions – saying the ‘Premier’ instead of Mikołajczyk, or the ‘President’ instead of Raczkiewicz, and I have been greatly helped by the wartime practice whereby many members of the Underground and Government were known by pseudonyms, nicknames, or

noms de guerre

, which can either be anglicized or translated into short, manageable forms. Hence Gen. Bór-Komorowski becomes ‘Boor’, Gen. Okulicki becomes ‘Bear Cub’, Premier Mikołajczyk becomes Premier ‘Mick’, and Lt. Fleischfarb becomes Lt. ‘Light’. I also took the liberty of modifying the spelling of Polish place names, thereby rendering them more readily pronounceable. I have no idea how my noble translator will cope with these eccentric forms when working on the Polish edition.

The modifications in the spellings of Polish names are aimed exclusively at easing the path of English-speaking readers. They will no doubt infuriate philological purists, but have been adopted in the belief that ordinary mortals are no less confused by official phonetic systems as by foreign orthography. In the case of place names, English forms are used wherever they exist – as in Warsaw, Cracow or Lodz. Where no English form is available, limited changes have been made. In the case of street names, the original forms have been translated if possible – as in New World Street, Long Street, Three Crosses Square, or Jerusalem Avenue. Otherwise, they, too, have been modified. In the case of personal names, well-known items such as Sikorski, Wojtyła, or Wał sa have been left in the original; and anglicized forms such as Casimir, Stanislas, or Thaddeus are used where appropriate. As far as possible, however, the difficulties have been obviated either by reducing surnames to initials – Maria D. for Maria D

sa have been left in the original; and anglicized forms such as Casimir, Stanislas, or Thaddeus are used where appropriate. As far as possible, however, the difficulties have been obviated either by reducing surnames to initials – Maria D. for Maria D browska or Adam M. for Adam Mickiewicz – or by resorting exclusively to the pseudonyms. Detailed explanations of the changes may be found in Appendix 35, or on occasion in relevant endnotes.

browska or Adam M. for Adam Mickiewicz – or by resorting exclusively to the pseudonyms. Detailed explanations of the changes may be found in Appendix 35, or on occasion in relevant endnotes.