Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw (20 page)

Read Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw Online

Authors: Norman Davies

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #War, #History

IV-A1 | partisans, Communists, illegal radio transmitters |

IV-A2 | sabotage, armed attacks, false documents |

IV-A3 | 1. right-wing organizations 2. courts 3. secret political organizations 4. conspiratorial resistance |

IV-A4 | protection service for Nazi officials |

IV-A5 | codes and decipherment |

IV-B | religious opposition: RC Church, Freemasons, Jewish affairs |

IV-C | arrests, prisons, press |

IV-D | hostages, foreigners, illegals |

IV-E | economic intelligence, postal security, desertion |

IV-N | special Gestapo assignments ( |

Department V (Crime), under

SS-Stbf.

H. Geisler, was the realm of the

Kripo

(Criminal Police). It was assisted by a large body of Polish detectives

working under German orders; and it supplied the higher ranks of the municipal ‘Blue Police’. Its special forces included the

Schupo

(‘Guard Police’) and the regular patrols of the

Orpo

(‘Order Police’), whose armoured trucks always stood waiting at sensitive points in the city, their engines running and their roof-mounted machine guns primed.

As in all totalitarian systems, some of the most powerful agencies operated outside the regular structures. One of these was the

Sonderkommando der Befehlshaber der Sicherheitspolizei

of

SS-Hstuf.

Alfred Spilker, whose influence in the Warsaw Gestapo was far greater than his lowly captain’s rank might have suggested. Another was the small

Rollkommando

(‘Hit Squad’) commanded by

SS-Ustuf.

Erich Marten. Equipped with a couple of fast cars, Marten’s men were empowered to intervene with force without regard to established procedures. The people whom they arrested did not appear on the lists of either the Paviak Jail or of the Gestapo. They disappeared without trace.

23

Excluding the Blue Police, the number and variety of armed and militarized German police units in Warsaw grew steadily. By 1943, they totalled nearly 6,000 men. Needless to say, they could call on the far better equipped and more numerous troops of the SS, the Wehrmacht, and the Luftwaffe at the least sign of trouble.

A long list of German officials earned themselves a reputation for needless nastiness, and in due course, all their names would be found on the ‘Head List’ of Underground revenge. Unfortunately for them, the Nazi Command judged their performance unsatisfactory. And in September 1943, one of the rising stars of the SS,

Brig.Fhr.

Franz Kutschera, was sent to Warsaw to steel their mettle. Kutschera was an Austrian, who served as a boy in the Austro-Hungarian navy, had studied in Budapest, and had lived in Czechoslovakia. So he was an East European expert. Joining the NSDAP in 1930, he was an early enthusiast who by the age of thirty-four was Gauleiter of his native Carinthia. After frontline service in France, he found his métier in the grisly business of keeping order in the east. He served successively as ‘SS and Police Chief’ in

Russland Mitte

and in Mogilev. Warsaw was no doubt a worthy promotion.

Warsaw’s role within the General Government was intended to be a secondary one. Warsaw was to absorb large numbers of refugees and expellees from the Reich, and would then gradually decline. It lost its capital status to ‘Krakau’, which the Nazis declared to be an ancient

German foundation and the only one to have a future. In 1940, an architect called Pabst prepared plans for a new Warsaw with a much-reduced urban area. It was one of many Nazi plans which never came to fruition.

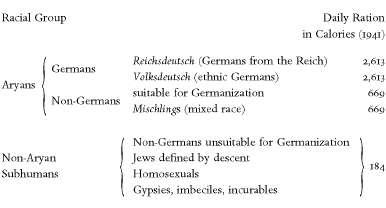

The Gestapo established its control over Warsaw in the early months by filtering the entire population, allocating them to racial categories and issuing them with the relevant documents. In order to live, every person required a Certificate of Racial Origin, an identity card (

Kennkarte

), and a ration card. Identity cards and ration cards were issued in accordance with the recipient’s racial classification, which in doubtful cases would be established after a detailed examination by Nazi ‘scientists’. The classification was drawn up in a strict hierarchy of superior and inferior groups, and with the clear intention of separating those whom the Nazis wanted to prosper from those who were doomed to fade away.

Later in the war, when the Nazis were desperate for recruits, they introduced a Category III, of non-Germans. These were people who in theory possessed some slight evidence of German ancestry and who were thereby qualified for military service.

Once this system was in place, Varsovians were entirely dependent on their wits and on the possession of ‘correct’ documents. The SS and the Gestapo who controlled it were backed up by militarized German police, by the local ‘blue police’, and by a ubiquitous army of informers. Anyone could be stopped on the street, arrested on suspicion, or, as increasingly happened, shot on the spot.

Even so, the Nazis possessed no ready-made plans for implementing their radical racial ambitions. In the first instance, their priorities lay with

eliminating potential troublemakers, building facilities, and segregating Jews.

The

Ausserordentliche Befriedungsaktion

(

AB-Aktion

, or Extraordinary Pacification Campaign) seems to have had its origins in the Nazi–Soviet Treaty of Friendship of 28 September 1939, which foresaw common action against ‘Polish agitators’. A conference attended by SS and NKVD officers took place in Cracow in March 1940, though its deliberations have not been documented. Shortly afterwards, the NKVD shot 25,000 Polish officers captured in the Soviet Zone, while the SS launched the

AB-Aktion

in the German Zone. The aim, in both cases, can only have been to kill the political and intellectual elite of the country. On this occasion, the SS could not match the performance of their Soviet partners. Some 3,500 persons were shot, and a larger consignment sent to Dachau and Sachsenhausen. In Warsaw, some 1,700 men and women were rounded up and driven 25km (fifteen miles) to an execution site at Palmiry on the edge of the Kampinos Forest. They included writers, academics, priests, Olympic athletes, parliamentary leaders, and politicians (but not Communists for the simple reason that Stalin’s purges had left very few Polish Communists for the Nazis to kill).

Himmler’s order to create a major concentration camp at Auschwitz for the purposes of the General Government can be dated to March 1940. It was designed to accommodate 10,000 inmates. A second camp at Auschwitz II-Birkenau began operation in October 1941 with a nominal capacity for 100,000, which was soon exceeded. Unlike Cracow and Lublin, Warsaw was not given a major concentration camp in its immediate vicinity, but in 1942 a relatively minor camp, KZ Warschau, was established in a closed-off block of streets within the city limits.

For reasons connected with its post-war fate, KZ Warschau has all but disappeared from the history books, but its grisly existence was real enough, and it features in the documentation of the Nuremberg Tribunal. Created by a series of personal directives from Himmler, it operated from October 1942 to August 1944. It consisted of a complex of five subcamps, which were linked by a series of purpose-built railway lines. One subcamp, in the western suburbs, had originally served in 1939 as a transit centre for POWs; two, on Goose and Bonifrater Streets, were located on the territory of the Ghetto; and two more were built in the immediate vicinity of Warsaw’s Western Station. In all, the complex contained 119 barracks with space for 41,000 inmates. A set of gas chambers was

constructed in a tunnel linking the two areas next to the Western Station, and three crematoria continued to function on the ‘Goose Farm’ site, right up to August 1944.

Attempts to ascertain the numbers and provenance of the people who died in KZ Warschau have been surrounded with unanswered questions. One estimate puts the total at 200,000, and relates the figure to the constant roundups, executions, and collective punishments perpetrated by the SS within Warsaw itself. Some commentators have linked it to the long-standing ‘Pabst Plan’ of 1940, which aimed to reduce the city’s population to half a million. At all events, there is every reason to separate the crimes committed in KZ Warschau from those connected with the Ghetto. And there was no shortage of eyewitness accounts:

During the Occupation . . . [stated Adela K.] I lived about 3000 yards from the tunnel near the Western Station. We saw covered German lorries there for the first time in the autumn of 1942. They were driven by SS men in black uniforms . . . and entered the tunnel from the Armatna Street side. . . . After the arrival of each transport, one could hear screams and smell gas . . .: and the Germans ordered all the inhabitants [of the district] to draw their curtains. Any window, where the curtains were not drawn, would be shot at . . .

24Many times, Felix J. personally watched as prisoners carried heaps of corpses from the tunnel and loaded them onto police trucks marked with the letters ‘W.H.’. The corpses did not show any traces of bullets. Members of the

Tod-Kommando

, which was manned by Poles, told him that the remains of people who had been gassed or had otherwise died in the camp, were taken to the crematoria on the ‘Goose Farm’ to be burned . . .

25

Oddly enough, Nazi policy in regard to the Catholic Church was less oppressive in the General Government than in the lands annexed directly by the Reich. In the Warthegau, for example, nine out of ten Polish parishes were closed, and the remaining clergy were subordinated to the German hierarchy. About 2,000 Polish priests were cast into Dachau alone, and with no whisper of protest from the Vatican. But in the General Government, the SS chose to let sleeping dogs lie. The primate was abroad. The bishops were docile. Other issues were more pressing.

There had been no Jewish Ghetto in pre-war Warsaw, so in November 1939 the Nazi command decided to create one. All persons who were

not in possession of Ayran papers were ordered to congregate in the pre-designated area. All non-Jewish residents of the Ghetto area were expelled, and notices were posted to the effect that any Jews caught outside the Ghetto without formal permission would be killed. Within a year, the segregation of the Jews was virtually complete. The operation cut them off from the rest of the city by a continuous 6m (twenty-foot) wall topped with barbed wire and surrounded by armed guards. It had baleful consequences. It meant that the SS could apply entirely separate measures to the Jewish population. It also meant that non-Jewish Varsovians had no means of readily helping their Jewish co-citizens in their distress.

The German presence in Warsaw was stifling. Two main sections of the city centre were designated

NUR FÜR DEUTSCHE

– ‘For Germans Only’. One of them, centred on the Adolf Hitler Platz (otherwise Pilsudski Square), contained a dense array of administrative institutions. The other, which ringed the Gestapo Headquarters on Schuch Avenue, was the official police district. Yet all the other districts and suburbs were given their military bases and fortified police stations. The pattern created by over twenty such bases and over a hundred police posts represented an even scatter rather than a limited number of large concentrations. It was admirably suited to the systematic patrolling of a quiescent populace. But it would be less effective when challenged by armed rebels. No single base was strong enough to act as a focus for offensive measures: and each base had to look to its own defences. What is more, the German military garrison was well below strength. It was designed to have 36,000 troops at its disposal; by mid-1944 it possessed barely half that.

The escalation of public violence was one of the features of German rule in Warsaw from 1943 onwards. When Nazi policies provoked open resistance both in the Ghetto and on the ‘Aryan side’, the Nazis did not see the causal link between oppression and defiance. Instead, they expressed astonishment at the disregard for their authority. On 10 October 1943, Varsovians listened to the pronouncement by megaphone of Governor Frank’s ‘Decree regarding the suppression of attacks on German reconstruction works’. Three days later, they watched helplessly as the SS started an extended programme of mass roundups. In contrast to previous policy, the victims were not sent off to the Reich for compulsory labour or to the concentration camps. They were destined for street executions, where large groups would be shot as a collective punishment, usually for unspecified crimes. The names, ages, and addresses of the executed were

posted at the site of their death, together with a second list of names of people who were held as hostages, and who would automatically be shot if anyone should dare to retaliate.