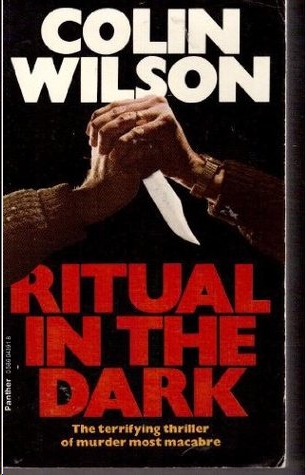

Ritual in the Dark

Read Ritual in the Dark Online

Authors: Colin Wilson

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Classics, #Mystery & Detective, #Traditional, #Traditional British

Ritual in the Dark

The terrifying thriller of murder most macabre

First book in the Gerard Sorme trilogy

by Colin Wilson

The other two books in the “trilogy” are “Man without a Shadow” (US: “The Sex Diary of Gerard Sorme”) and “The God of the Labyrinth” (US: “The Hedonists”).

Back Cover:

WILSON’S CLASSIC NOVEL

OF CONTEMPORARY MURDER

A wave of sickening deaths hits the streets of modern London. Young women, mainly prostitutes, are found mangled and mutilated. The police are baffled, the press outraged—not since Jack the Ripper has such a sinister brand of violent murders been unleashed. Is the culprit a homicidal maniac or a coldblooded, calculating killer wreaking a personal vendetta on a corrupt and callous society?

In this best-selling, blood-blanching chiller, Colin Wilson examines the murderous motives of a depraved mind and creates a story of biting realism which will stagger the imagination and shock the intellect. . .

Gerard Sorme, a young but world-weary writer, accidentally meets a wealthy ballet critic, Austin Nunne, who introduces Sorme to a cosmopolitan world he had previously only dreamed of, as well as gradually revealing himself as a pervert, a sadistic homosexual with a taste for exotic perfume and rooms draped in black. But Sorme extends his acquaintance further to include a Roman Catholic priest, a German pathologist, a Van-Gogh-like painter and two women, a niece and aunt, who in turn become his mistresses. Against the background of a series of baffling, sickening murders, Sorme finds himself drawn closer and closer to the sexual maniac who is terrorizing the streets of London—and whom he knows to be somehow connected with his newly acquired friends. . .

“Not since Dickens has a British fiction-writer dealt with murder in a book of such size and seriousness”—Sunday Express

“What an unforgettable, really great evocation. Terrible and tragic insight. . . an important book”—Sunday Times

“Exhilarating reading”—The Listener

Granada Publishing Limited

Published in 1976 by Panther Books Ltd

Frogmore, St Albans, Herts AL2 2NF

First published by Victor Gollancz Ltd 1960

Copyright © Colin Wilson 1960

Made and printed in Great Britain by

Richard Clay (The Chaucer Press) Ltd

Bungay, Suffolk

Set in Monotype Plantin

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way

of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise

circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of

binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without

a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the

subsequent purchaser. This book is published at a net price and

is supplied subject to the Publishers Association Standard Conditions

of Sale registered under the Restrictive Trade Practices Act, 1956.

For Bill Hopkins

I should like to acknowledge the help of the following: Richard Buckle, for refreshing my memory on details of his Diaghilev exhibition and suggesting many improvements in Chapter One; Bill Hopkins, Stuart Holroyd, Laura del Rivo and John Braine for detailed criticism of the book; Dr Francis Camps for advice on matters of forensic medicine; John Melling and Joy Wilson for preparing the manuscript for press; Philip Stephens for advice on legal matters and police procedure; Pat Pitman, for reading the manuscript for mistakes, and for some stimulating (if unlikely) theories about the identity of Jack the Ripper; finally, Victor Gollancz for constant sympathy and help, and for his many suggestions for improvement.

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

HE CAME out of the Underground at Hyde Park Corner with his head lowered, ignoring the people who pressed around him and leaving it to them to steer out of his way. He disliked the crowds. They affronted him. If he allowed himself to notice them, he found himself thinking: Too many people in this bloody city; we need a massacre to thin their numbers. When he caught himself thinking this, he felt sick. He had no desire to kill anyone, but the hatred of the crowd was uncontrollable. For the same reason, he avoided looking at the advertisements that line the escalators of London tubes; too many dislikes were triggered off by the most casual glimpse. The half-clothed forms that advertised women’s corsets and stockings brought a burning sensation to his throat, an instantaneous shock, like throwing a match against a petrol-soaked rag.

A thin brown drizzle fell steadily; the passing traffic sprayed muddy water. He buttoned the raincoat and turned up its collar, then opened the woman’s umbrella he carried suspended by its loop from his wrist. The crowd thinned as he crossed

Outside the gilded wrought-iron gates he stopped and fumbled for his money. The doorway of the house was hidden by a striped tent surmounted by a Russian onion dome; on either side of this stood statues of two enormous Negroes, leaning on the marble archway that formed the entrance to the tent. He lowered the umbrella, shaking it to dislodge the raindrops. Behind the Negroes, the walls of the house looked black and desolate.

The entrance hall smelt of damp clothes. A queue of half a dozen people was waiting at the boxoffice. The inside walls of the tent were covered with red and gold striped paper.

There was some delay at the boxoffice. A middle-aged man was protesting with a foreign voice:

Nevertheless, I am a student at the London School of Economics. It is merely that I have forgotten my card. I have a British Museum Reading Room card if that is any good. . .

Sorme produced a book from the side pocket of his jacket, and began to read. The queue moved forward again.

He became aware that the man in front of him was looking down at his book, trying to read its title from the page heading. He looked up, and met a pair of narrow, brown eyes, that turned away immediately with embarrassment. In that moment, he had registered a thin, long-jawed face that in some way struck him as oddly familiar. It was ugly, in a pleasant way, covered with small indentations that could have been pock-marks. A moment later, the man bought his ticket, and Sorme had a chance to observe him more fully. The examination brought no recognition. He was taller than Sorme, although Sorme was slightly over six feet tall. His dark grey suit was well cut. The thin face had high cheekbones, and eyes that slanted. It was so familiar that Sorme stared a moment too long, and suddenly found himself looking into the slanting brown eyes again. They smiled at him briefly as the man turned away, and Sorme was suddenly certain that he had never seen him before. The ticket-seller was asking: Student?

Yes.

One and sixpence please. Catalogue?

The stairway that led out of the tent curved round the canvas walls, and exposed the rusty scaffolding that supported it. He walked quickly, disliking the unpleasant memories aroused by the scaffolding. The stairs led to a doorway that had been constructed from a first-floor window, and formed the entrance to the exhibition. The first room immediately dissipated the mood of dislike. It had been designed to look like a Paris street, with iron railings, and a view of the Seine between the houses. Under the leaves of an overhanging tree, a huge poster displayed the words: THEATRE DES CHAMPS ELYSEES. BALLETS RUSSES. The enormous drawing of Nijinsky as the Spectre of the Rose was signed by Cocteau.

The place was warm; there was no one else in the room, and he lost the feeling of tension that the rain and the crowds had induced. There was a sound of music coming from a loudspeaker in another room. He slipped the book back into the jacket pocket, plunged his hands deep into his raincoat pockets, and gave himself up completely to the sense of nostalgia evoked by the room. He stood there for a few moments unmoving, until he heard footsteps and voices on the stairway, then walked quickly past the poster of Pavlova that faced Nijinsky, and mounted the narrow wooden stair to the second floor.

The music was louder there. He recognised the final dance from The Firebird, the soft, drawn-out horn call. It sent a warm shock of pleasure through the muscles of his back and shoulders, and stirred the surface of his scalp. People were already mounting the stairs behind him. He hurried on into the well-lit room. There was only one other person in it: the man who had stood in front of him in the queue. The voices and footsteps that came from the stairway drove him forward into the next room. A violent hatred arose in him of the talking people who talked away emotions into words. A drawling, cultured voice was saying:

. . . and we nearly got a snap of him. He was there on the beach, just changing into a pair of bathing trunks. Lettie grabbed her camera, but she wasn’t quick enough. . . he got them on. Should have been worth something—a shot of Picasso in the raw. . .

The music had stopped. The voice faltered, embarrassed at the silence. Abruptly the music began again, a violent, discordant clamour that exploded in the small room and drowned all other sounds. He recognised Prokoviev’s Scythian Suite, and smiled. The din was shaking the glass case in the middle of the room; it isolated him as effectively as silence. He examined with satisfaction a design by Benois.

The rooms were not crowded. He worked through them slowly, returning to the first room when the people behind him—an army officer with two girls—caught up with him.

*

*

*

An hour later, the loudspeakers were relaying The Three-cornered Hat, and he was again on the first floor, in the portrait gallery. The heat was making him sleepy. There was a curious scent hanging in the air which he half-suspected of possessing an anaesthetic quality. As he paused in front of a portrait of Stravinsky, he noticed the bust. It stood on a cube of marble, directly below an oil painting of a ballerina in a white dress. The inscription underneath said: Nijinsky, by Una Troubridge. He had remembered then of whom the stranger reminded him. It was Nijinsky.

Somewhere, a long time before, he had seen a photograph that caught the same expression, and the thin, faun-like face had impressed itself on his mind. As he stared at it now, the resemblance was no longer so obvious. Automatically he looked around to see if the man was anywhere near. He was not. Idly, he wondered whether he might be any relation of Nijinsky, his son perhaps. He could remember no son; only a daughter. Anyway, the bust was not really like him. It was not really like Nijinsky either; it had been idealised.

The man was in the Chirico room at the top of the stairs; he stood, leaning on an umbrella, examining one of the designs. Sorme crossed the room and stood close to him, where he could watch his face out of the corner of his eye. The resemblance was certainly there; it had not been imagination. By turning his head a little more, as if examining the design to his left, he could examine the face in profile.

Without looking at him, the stranger said abruptly:

He should have done more ballet designs.

For a moment, Sorme supposed he was addressing somebody on his left-hand side, then realised, equally quickly, that they were alone in the room. The man had not turned his face from the design he was examining. Sorme said: I beg your pardon?

Chirico. He never did anything better than these designs for Le Bal. Don’t you agree?

I don’t know, Sorme said, I don’t know his work.

The stranger looked at him and smiled, and Sorme realised that he must have been watching him in the glass covering the design ever since he came in. He began to feel slightly irritated and embarrassed. Something in the man’s voice told him instantly he was a homosexual. It was a cool, slightly drawling voice.

You know, the man said, I could have sworn I knew you when you came in. Do I?

I don’t think so.

The eyes rested on him detachedly; he had the air of a Regency buck studying a horse. Sorme thought: Damn, he thinks I’m queer too.

I thought you knew me, the man said, you looked at me as if you knew me.

His voice was suddenly apologetic. Sorme’s irritation disappeared. He cleared his throat, lowering his eyes.

As a matter of fact, I did think I recognised you. But I don’t think that’s possible.

Perhaps. My name is Austin Nunne. I was quite sure I knew you,

Austin Nunne. . . ? Did you write a book on ballet?

Yes. And a slim volume on Nijinsky.

Sorme was excited and pleased, as the memory returned: the photograph of Nijinsky.

Of course I remember you. I’ve read them both. So that’s why I thought I knew you!

You surprise me. It’s a very bad photograph of me on the dust jacket.

No, I haven’t seen that. But the photograph of the Nijinsky bust. Wasn’t that in your book?

The Una Troubridge? O no. Karsarvina found this one in a junk-shop in St Martin’s Lane. I didn’t even know it existed. But I think I know what you mean. The photo of Nijinsky in L’Après-Midi. The head and shoulders?

Sorme suddenly felt irritated and depressed. He felt that his enthusiasm had placed him in the position of an admirer, a ‘fan’. Nunne suddenly turned away, saying in a bored voice:

Anyway, they’re neither of them very typical of Nijinsky. To tell the truth, I used that L’Après-Midi photo because friends said it looked like me.

Sorme looked at his watch, saying: Well, I hope you didn’t mind my asking?

Not at all. Are you in a hurry to go? Have you been all round?

No. But I’ve been here for an hour and a half. I don’t feel as if I could take any more.

You’re undoubtedly right. It’s my fourth time around. I saw it when it opened in Edinburgh.

Sorme said embarrassedly: I must go.

Look here, why don’t you come and have a drink? It’s about opening time.