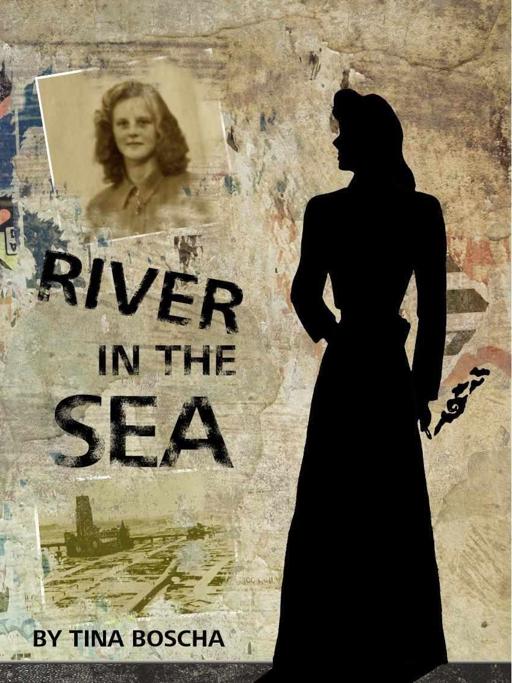

River in the Sea

Authors: Tina Boscha

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

Kindle Edition

Copyright © 2011 by Tina Boscha

Kindle Edition License Notes

This book is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be resold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return it to Amazon and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Cover design by Kai Persons

www.kaipersons.com

Cover photos courtesy of Linda Boscha

and the

National Archives 208-PR-10L-3

For more information please visit

www.tinaboscha.com

Praise for

River in the Sea

:

“The book is well written and historically significant…Boscha has best-seller potential.”

—Portland Book Review

“Two words I could say to sum up this book are ‘enchanting’ and ‘emotional’…it blew me away.”

—RJ Moore

“Her book is engrossing and horrifying at the same time, a tale of what it’s like to be hungry, sick and worried that life, family and freedom will never be the same again…”

—Eugene Register-Guard

“I was riveted within a few dozen pages as one of the pivotal events of the book unfolded... I could not put it down.”

—The Blue Stockings Society

“This enovel is beautifully written, with descriptions and details that are exquisite and eloquent. Boscha is not only a competent writer, she excels at it.”

—eNovel Reviews

“Her character, Leen, draws you in and makes you forget that you are even reading ... you laugh with Leen, get mad with Leen, and yes, even cry with Leen.”

—K. Ristau

To Pieter Bosscha

and

Leentje De Graaf

aka

my wonderful mom and dad, Pete and Linda Boscha

&

to the reader:

by selecting this book, you’ve made my lifelong dream come true

Note to the reader:

While this book is inspired by several events experienced by my mother and her family during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, I have taken the liberty of altering several elements, including timelines, characters, event attribution, and names. At its heart, this is a work of fiction and is not intended to be factual.

Every effort has been made to ensure an error–free reading experience. However, typos or formatting problems occasionally slip in. Please feel free to contact me at [email protected] to report any mistakes.

1.

At fifteen years old, Leentje – Leen, as she was called – De Graaf did not know how to diagnose the mix of frustrations and emotions that collected into the tiniest of split–second decisions, spiraling into a flex of the muscle at the top of her knee, then hurtling down into a thrust from the ball of her right foot, pushing hard on the gas.

On that third Saturday in October, 1944, she knew in the same way she knew that rain was coming, or that her brother Issac would choose a scowl before a smile, that the war still was not over. It was part of the backdrop of her daily life that the Allieds had not yet crossed the Rhine into Friesland.

She was aware that she was tired, but like the war, exhaustion was expected; it was truth. It seemed wherever she was at, she worked; ever since Herr Müller replaced Mr. Dykstra, the headmaster of Wierum’s small school, shouting numbers at her in

Deutsch

, she hadn’t been to school. Her baby sister, Renske, had never been at all.

She knew she was strong, with hard shoulders and a straight back, and, if it was her Pater asking her, a readiness to say yes to the task at hand, and yet this made her a misfit, and beyond that, a disappointment to her mother.

But what was foremost on her mind that day, before she ever found herself in the truck, stepping on the gas, was the stolen packet of salt shoved deep in her skirt pocket, wrapped carefully in a single sheet of waxed paper.

Leen reached an arm into her hand–me–down coat, and just as she started to put her other arm through the sleeve, Mr. Deinum patted her on the shoulder. She jumped at his touch even though she knew he stood nearby.

“Sorry, Leen,” he said, and by his easy, nonchalant tone she was sure he knew. She waited for him to clear his throat and deepen his tone, pause, then tell her to empty her pocket, to return the salt, and to report to her

Mem and Pater that she no longer had a job. She could not bear Mem’s reaction, her frozen face pulling deeper into a silent frown.

Instead, Mr. Deinum said, “Good work today.” The back door, where she entered and left, was off the kitchen, and he sat down at the table with the cup of coffee Leen had warmed for him in the last few minutes of her shift, her hand shaking when she poured it into the thin blue cup. He took a sip. Suddenly he held it up, as if he could see through the porcelain, and made a mock gagging noise. “Not enough

suker

, you know?”

Leen nodded. She leaned slightly against the door, keeping her coat around her. There were a lot of things she wanted to say to him. First, that she didn’t do a very good job, that she swept flour into corners, refolded damp towels rather than wash them after one use. Second, that she liked him the most of any adult she knew, save her own father, and was sorry for stealing from him. Third, that she had no plans to stop. They needed it too badly.

Instead, she said, “I know. My

moeder

tries to make cakes with less. It’s not the same.”

Mr. Deinum shrugged, sighing. Sometimes she could tell his cheerfulness was an effort. Today, it made her nervous, so she kept talking. “The tea isn’t very good either. But I’m used to it now.” She told herself to say goodbye, to get going, she needed to get to the deliveries and then home where she could place her illicit package

on the kitchen table and wait to see if her mother smiled. It was Mem’s idea for Leen to work at the Deinum’s, to teach her, finally, how to keep a house, and for Leen to get one of the most coveted items since the rations began years ago: salt.

And it also meant getting Leen out of the fields. Though if Leen had her way, she’d be back getting dirty in the heavy, fertile clay, driving the tractor or dropping in sprouted new potatoes, drinking coffee with Issac and Pater in whoever’s field they were working that day, and eating bacon rolled up in soft bread for lunch. Leen loved how the days in the fields were ordered by the season and the weather and the condition of the crop itself, how the work required clean–up only when a task was completed, not because it was considered good practice or that Tuesday was the agreed–upon day to iron all the linens.

Instead, six days a week Leen De Graaf traveled to Dokkum to work as a maid for the Bakker Deinum and his wife. This also meant that six days a week she had to pass the German camp, speeding past it at 7 a.m., and speeding even faster at 5, when it was just getting dark. It was always worse in the evening, the adrenaline surge in her toes pushing against the pedals of her creaky bicycle, her thighs burning and her hands cramping with her iron grip on the handlebars. At least on Saturdays, she could drive – illegally, still – her father’s truck. Then she could drive fast, keeping the camp a fixed blur in her peripheral vision until it became nothing at all. Today should have been no different. Except that she had added another regularity to her routine: theft. She was now two things she despised: a maid and a thief.

In the dim light, provided by smoky lamps lit with diesel oil and beeswax candles, Mr. Deinum looked tired. “The things you miss,” he said softly. “The little things. Sugar in your coffee.”

Leen watched Mr. Deinum grimace as he took another sip. Pressing her hand against her pocket that housed the coveted crystals, she whispered, “I should go.” She cleared her throat, embarrassed at her own voice.

“Deliveries today?”

She shifted her weight and swore she could hear the paper crackle. Was he teasing her? Baiting her? That wasn’t like him. When she first took over the deliveries from Issac three years ago, Mr. Deinum had been one of her first customers. He never once asked how a twelve–year–old girl could be such a good driver, or asked if Issac was ill when she first started delivering on her own, willfully forgetting the constant conscription raids that made it too dangerous for Pater or Issac especially to work outside of Wierum. Nor did he try to help her with the work, letting her sweat and grunt as she ably unloaded sacks of flour and sugar. When she was finished, he gave her chocolate milk for free, and insisted she sit and drink it. “You need to rest, you’re working so hard,” he’d say, and Leen liked him for that alone, because no other Frisian she knew said anyone worked too hard.

Her mouth felt like it was filled with dry beans when she answered, “

Ja

, but not so many. Not many have the money to pay anymore.” Internally she repeated to herself:

Leave now. You have to leave now.

“You take trades?”

Leen’s heartbeat spiked. Of course. He suspected her of stealing the salt to trade on the black market. And he was partially right. “The trades are often worth more than the money,” she said, reciting something she’d heard Pater say.

Mr. Deinum stared at his cup. He said, “Say hi to your brother for me,

ja

? I haven’t seen Issac in far too long.” She knew he liked to visit with her brother. His own son, Klaus, had been unexpectedly caught, despite the work of the Resistance, and sent to Germany for forced labor, gone over two years now.

She started to turn the doorknob. “I should go,” she said again. This time she felt like she was shouting. “I will tell Issac you said hello.” He was still looking at his coffee, no longer attempting to keep her there for her company. She felt ashamed at what she had taken.

But not enough to take it out of her pocket and confess.

“

Doeie

,” she said quietly, using the casual goodbye. Leen closed the door but not before Mr. Deinum called after her to be careful. He said the same thing every time she left.

Inside the truck she exhaled. She pulled out the salt and placed it on the seat next to her. She checked the list Pater had given her that morning and noted there were only two places to go. Then home.

She breathed in deeply and started the truck. At that moment, she was sure she’d gotten away with it.

She was wrong.

She rushed through the deliveries, Pater’s other business that made the best use of the rusted, damaged vehicle. Back inside the truck, Leen tossed the German–issued tobacco onto the passenger seat. Mrs. Waaten couldn’t pay with anything else.

She gripped the wheel and put it into gear. She steered the truck onto the lane that led her towards Wierum. She should have felt relief at being finished, but she was filled with steam, just as anxious as she’d been leaving the bakery. She picked up the packet and held it between her palm and the steering wheel.

I should keep it

, she thought. What if she pulled over, right then and there, and licked the salt off the paper until she wore holes in her gums and the roof of her mouth? But she knew she would never do it. Mem had plans. They would save as much as they could so she could use it when Pater next traded for a pig that they would butcher to fry chops and cure bacon all in one day, stretching the meat as much as possible until they could trade for another.