River of Blue Fire (30 page)

Read River of Blue Fire Online

Authors: Tad Williams

This, which started out as an unhappy thought, suddenly struck him with its absurd side as well, and the long-withheld laugh burst out of him.

“I hope you are enjoying yourself,” the tortoise said in a frosty tone.

“It's not you,” Orlando said, gaining control again. “I just thought of something. . . .” He shrugged. There was no way to explain.

As they neared the bank of the river, they could see something sparkling on the shore and hear faint but lively music. A large dome stood on the floor just at the water's edge. Light streamed out of it through hundreds of small holes and a variety of odd silhouettes were passing in and out of a larger hole in the side. The music was louder now, something rhythmic but old-fashioned. The strange shapes seemed to be dancingâa group of them had even formed a line in front of the dome, laughing and bumping against each other, throwing their tiny wiggling arms in the air. It was only as the canoe drew within a stone's throw of the bank that its crew could finally see the merrymakers properly.

“Scanbark!” Fredericks whistled. “They're vegetables!”

Produce of all types staggered in and out of the main door of the dome beneath a large illuminated sign which read “

The Colander Club

.” Stalks of leek and fennel in diaphanous flapper dresses, zucchini in zoot suits, and other revelers of a dozen well-dressed vegetal varieties packed the club to overflowing; the throng had spilled out onto the darkened linoleum beach in cornucopiate profusion, partying furiously.

“Hmmph,” the tortoise grunted disapprovingly. “I hear it's a very seedy crowd.” There was not the slightest suggestion of humor.

As Orlando and Fredericks stared in amazed delight, a sudden, hard impact shivered the canoe and tipped it sideways, almost tumbling Orlando overboard. The tortoise fell against the railing, but Fredericks shot out a hand and dragged him down into the bottom of the boat where he lay, waggling his legs violently in the air.

Something struck the boat again, a jarring thump that made the wood literally groan. Strike Anywhere was fighting to keep the canoe afloat in the suddenly hostile waters, his big hands whipping the paddle from one side of the canoe to the other as it threatened to overturn.

As Orlando struggled for balance in the bottom of the canoe, he felt something scrape all the way down the keel beneath him. He scrambled onto his hands and knees to see what had happened.

A sandbar

, he thought, but then:

A sandbar in the middle of a kitchen floor

?

He peered over the side of the pitching canoe. In the first brief moment he could see only the agitated waters splashing high, glowing in the lights from the riverside club, then something huge and toothy exploded up out of the water toward him. Orlando squealed and dropped flat. Huge jaws gnashed with a loud

clack

just where his head had been, then banged against the edge of the canoe hard enough to rattle his bones as the predatory shape fell back into the water.

“There's something . . . something tried to bite me!” he shouted. As he lay, shivering, he saw another vast pair of jaws rise on the far side of the canoe, streaming water. They opened and then clashed their blunt teeth together, then the thing slid back down out of sight. Orlando groped at his belt for his sword, but it was gone, perhaps overboard.

“Very bad!” Strike Anywhere shouted above the splashing. The canoe sustained yet another heavy blow, and the Indian fought for balance. “

Salad tongs

! And them heap angry!”

Orlando lay beside Fredericks and the feebly thrashing tortoise in the bottom of the canoe, which was rapidly filling with water, and tried to wrap his mind around the idea of being devoured by kitchen utensils.

D

READ was reviewing the first batch of data from Klekker and Associates on his southern Africa queries, and enjoying the solid bodily hum of his most recent hit of Adrenax, when one of his outside lines began blinking at the corner of his vision. He turned down the loping, percussive beat in his head a little.

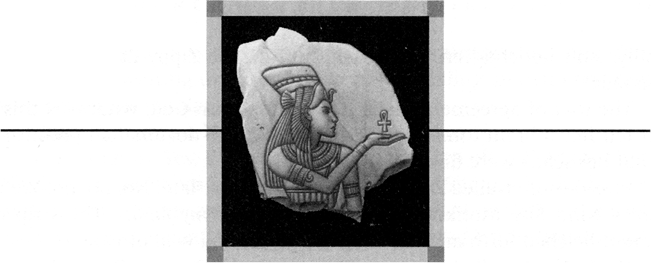

The incoming call overrode his voice-only default, opening a window. The new window framed an ascetic brown face surmounted by a wig of black hemp laced with gold thread. Dread groaned inwardly. One of the Old Man's lackeysâand not even a real person. It was the strangest kind of insult. Of course, Dread considered, with someone as rich and isolated as the Old Man, maybe he didn't even realize it was an insult.

“The Lord of Life and Death desires to speak with you.”

“So he wants me to come visit the film set?” It was a reflexive remark, but Dread was irritated with himself for wasting sarcasm on a puppet. “A trip to V-Egypt? To whatever it is, Abydos?”

“No.” The puppet's expression did not change, but there was a greater primness in its speech, a tiny hint of disapproval at its levity. Maybe it wasn't a Puppet after all. “He will speak to you now.”

Before Dread had more than an instant to be surprised, the priest winked out and was replaced by the Old Man's green-tinged death-mask. “Greetings, my Messenger.”

“And to you.” He was taken aback, both by the God of Death's willingness to dispense with formalities, and by the knowledge of his own double game, emblemized by the documents even now sitting on the top level of his own system. The Old Man couldn't just pop in past the security and read them while the line was open, could he? Dread felt a sudden chill: it was very hard to guess what the Old Man could or couldn't accomplish. “What can I do for you?”

The strange face peered at him for a long moment; and Dread suddenly very much wished he had not answered the call. Had he been found out? Was this the lead-up to the horrible and only eventually fatal punishment that his treachery would earn?

“I . . . I have a job for you.”

Despite the odd tone in his employer's voice, Dread felt better. The old man didn't need to be subtle with someone as comparatively powerless as he, so it seemed unlikely he knew or even suspected anything.

And I won't be powerless forever

. . . .

“Sounds interesting. I've pretty much tied up all the loose ends from Sky God.”

The Old Man continued as though Dread hadn't spoken. “It's not in your usual . . . field of expertise. But I've tried other resources, and haven't . . . haven't found any answers.”

Everything about the conversation was strange. For the first time, the Old Man actually sounded . . . old. Although the bandit adrenals were racing through his blood, urging him either to flee or fight, Dread began to feel a little more like his normal, cocky self. “I'd be glad to help, Grandfather. Will you send it to me?”

As if this use of the disliked nickname had woken up his more regular persona, the mask-face abruptly frowned. “Have you got that music playing? In your head?”

“Just a bit, at the moment . . .”

“Turn it off.”

“It's not very loud. . . .”

“Turn it

off

.” The tone, though still a bit distracted, was such that Dread complied instantly. Silence echoed in his skull.

“Now, I want you to listen to this,” the Old Man said. “Listen very carefully. And make sure you record it.”

And then, bizarrely, unbelievably, the Old Man began to sing.

It was all Dread could do not to laugh out loud at the sheer unlikeliness of it all. As his employer's thin, scratchy voice wound through a few words set to an almost childishly basic tune, a thousand thoughts flitted through Dread's mind. Had the old bastard finally lost it, then? Was this the first true evidence of senile dementia? Why should one of the most powerful men in the worldâin all of

history

âcare about some ridiculous folk song, some nursery rhyme?

“I want you to find out where that song comes from, what it means, anything you can discover,” the Old Man said when he had finished his creaky recital. “But I don't want it known that you're doing the research, and I

particularly

don't want it to come to the attention of any of the other Brotherhood members. If it seems to lead to one of them, come back to me immediately. Do I make myself understood?”

“Of course. As you said, it's not in my normal line. . . .”

“It is now. This is

very important

.”

Dread sat bewildered for long moments after the Old Man had clicked off. The unaccustomed quiet in his head had been replaced now with the memory of that quavering voice singing over and over, “

an angel touched me . . . an angel touched me

.”

It was too much. Too much.

Dread lay back on the floor of his white room and laughed until his stomach hurt.

CHAPTER 12

The Center of the Maze

NETFEED/ADVERTISEMENT: ELEUSIS

(

visual: happy, well-dressed people at party, slo-mo

)

VO: “Eleusis is the most exclusive club in the world. Once you are a member, no doors are closed to you

.

(

visual: gleaming, angled key on velvet cushion in shaft of light

)

“

The owner of an Eleusis Key will be fed, serviced, and entertained in ways about which ordinary mortals can only dream. And all for free. How do you join? You can't. In fact, if you're hearing about Eleusis for the first time, you'll almost certainly never be a member. Our locations are secret and exclusive, and so is our membership. So why are we advertising? Because having the very, very best isn't as much fun if no one else knows about it

. . .”

H

IS first thought, as he struggled toward the surface of yet another river, was;

I could get tired of this very quickly

.

His second, just after his head broke water, was:

At least it's warmer here

.

Paul kicked, struggling to keep afloat, and found himself beneath a heavy gray sky. The distant riverbank was shrouded in fog, but only a few yards away, as if placed there by the scriptwriter of a children's adventure serial, bobbed an empty rowboat. He swam to it, fighting a current that although gentle was still almost too much for his exhausted muscles. When he reached the boat, he clung to its side until he had caught his breath, then clambered in, nearly turning it over twice. Once safely aboard, he lay down in the inch of water at the bottom and dropped helplessly into sleep.

He dreamed of a feather that glittered in the mud, deep beneath the water. He swam down toward it, but the bottom receded, so that the feather remained always tantalizingly out of reach. The pressure began to increase, squeezing his chest like giant hands, and now he was aware also that just as he sought the feather, something was seeking himâa pair of somethings, eyes aglitter even in the murky depths, sharking behind him as the feather dropped farther from his grasp and the waters grew darker and thicker. . . .

Paul woke, moaning. His head hurt. Not surprising, really, when he considered that he had just made his way across a freezing Ice Age forest and fought off a hyena the size of a young shire horse. He examined his hands for signs of frostbite, but found none. More surprisingly, he found no sign of his Ice Age clothes either. He was dressed in modern clothing, although it was hard to tell quite how modern, since his dark pants, waistcoat, and collarless white shirt were all still dripping wet.

Paul dragged his aching body upright, and as he did so put his hand on an oar. He lifted it and hunted for a second so that he could fill both of the empty oarlocks, but there was only the one. He shrugged. It was better than no oar at all. . . .

The sun had cleared away a bit of the fog, but was itself still only directionless light somewhere behind the haze. Paul could make out the faint outlines of buildings on either side now, and more importantly, the shadowy shape of a bridge spanning the river a short distance ahead of him. As he stared his heart began to beat faster, but this time not from fear.

It can't be

. . . He squinted, then put his hands on the boat's prow and leaned as far forward as he dared.

It is . . . but it can't be

. . . . He began to paddle with his single oar, awkwardly at first, then with more skill, so that after a few moments the boat stopped swinging from side to side.

Oh, my sweet God

. Paul almost could not bear to look at the shape, afraid that it would ripple and change before his eyes, become something else.

But it really is. It's Westminster Bridge

!

I'm home

!

He still remembered the incident with a burn of embarrassment. He and Niles and Niles' then-girlfriend Portia, a thin young woman with a sharp laugh and bright eyes who was studying for the Bar, had been having a drink in one of the pubs near the college. They had been joined by someone else, one of Niles' uncountable army of friends. (Niles collected chums the way other people kept rubber bands or extra postage stamps, on the theory that you never knew when you might need one.) The newcomer, whose face and name Paul had long since forgotten, had just come back from a trip to India, and went on at length about the scandalous beauty of the Taj Mahal by night, how it was the most perfect building ever created, and that in fact its architectural perfection could now be scientifically proved.

Portia suggested in turn that the most beautiful place in the world was without question the Dordogne in France, and if it hadn't become so popular with horrible families in electric camping wagons with PSATs on the roof, no one would dare question that fact.

Niles, whose own family traveled extensivelyâso extensively that they never even used the word “travel,” any more than a fish would need to use the word “swim”âopined that until all those present had seen the stark highlands of Yemen and experienced the frightening, harsh beauty of the place, there was no real reason to continue the conversation.

Paul had been nursing a gin and tonic, not his first, trying to figure out why sometimes the lime stayed up and sometimes it went to the bottom, and trying equally hard to figure out why spending time around Niles, who was one of the nicest people he knew, always made him feel like an impostor, when the stranger (who had presumably had a name at that time) asked him what he thought.

Paul had swallowed a sip of the faintly blue liquid, then said: “I think the most beautiful place in the world is the Westminster Bridge at sunset.”

After the explosion of incredulous laughter, Niles, perhaps hoping to soften his friend's embarrassment, had done his best to intimate that Paul was having a brilliant jape at the expense of them all. And it

had

been embarrassing, of course: Portia and the other young man clearly thought he was a fool. He might as well have worn a tattoo on his forehead that said “Provincial Lout.” But he had meant it, and instead of smiling mysteriously and keeping his mouth shut, he had done his best to explain why, which had of course made it worse.

Niles could have said the same thing and either made it a brilliant joke or defended it so cleverly that the others would have wound up weeping into their glasses of merlot and promising to Buy British, but Paul had never been good with words in that wayânever when something was important to him. He had first stammered, then muddled what he was trying to say, and at last became so angry that he stood up, accidentally knocking over his drink, and fled the pub, leaving the others shocked and staring.

Niles still tweaked him about the incident from time to time, but his jokes were gentle, as though he sensed, although he could never really understand, how painful it had been for Paul.

But it had been trueâhe thought then, and still did, that it was the most beautiful thing he knew. When the sun was low, the buildings along the north bank of the Thames seemed fired with an inner light, and even those thrown up during the intermittent cycles of poor taste that characterized so much of London's latter-day additions took on a glow of permanence. That was England, right there, everything it ever was, everything it ever could have been. The bridge, the Halls of Parliament, the just-visible abbey, even Cleopatra's Needle and the droll Victorian lamps of the Embankmentâall were as ridiculous as could be, as replete with empty puffery as human imagination could contrive to make them, but they were also the center of something Paul admired deeply but could never quite define. Even the famous tower that contained Big Ben, as cheapened by sentiment and jingoism as its image was, had a beauty that was at once ornate and yet breathtakingly stark.

But it was not the kind of thing you could describe after your third gin and tonic to people like Niles' friends, who ran unrestrained through an adult world that had not yet slowed them down with responsibility, armed with the invincible irony of a public-school upbringing.

But if Niles had been where Paul had just been, had experienced what Paul had experienced, and could see the bridge nowâthe dear old thing, appearing out of the fog beyond all hopeâthen surely even Niles (son of an MP and now himself a rising star in the diplomatic service, the very definition of urbane) would get on his knees and kiss her stony abutments.

Fate turned out to be not quite as generous a granter-of-wishes as it might have been. The first disappointmentâand as it turned out, the smallestâwas that it was not, in fact, sunset. As Paul paddled on, almost obsessed with the idea of docking at the Embankment itself, instead of heading immediately to shore in some less auspicious place, the sun finally became visible, or at least its location became less general: it was in the east, and rising.

Morning, then. No matter. He would climb ashore at the Embankment as planned, surrounded no doubt by staring tourists, and walk to Charing Cross. There was no money in his pockets, so he would become a beggar, one of those people with a perfunctory tale of hardship that the begged-of barely acknowledged, preferring to tithe and escape as quickly as possible. When he had raised money for tube fare, he would head back to Canonbury. A shower at his flat, several hours of well-deserved sleep, and then he could return to Westminster Bridge and watch the sunset properly, giving thanks that he had made his way back across the chaotic universe to sublime, sensible London.

The sun lifted a little higher. A wind came out of the east behind it, bearing a most unpleasant smell. Paul wrinkled his nose. For two thousand years this river had been the lifeblood of London, and people still treated it with the same ignorant unconcern as had their most primitive ancestors. He smelled sewage, industrial wastesâeven some kind of food-processing outflow, to judge by the sour, meaty stenchâbut even the foulest odors could not touch his immense relief. There on the right was Cleopatra's Needle, a black line in the fogs that still clung to the riverbank, backdropped by a bed of bright red flowers fluttering in the breeze. Gardeners had been hard at work on the Embankment, to judge by the yards and yards of brilliant scarlet. Paul was reassured. Perhaps there was some civic ceremony going on today, something in Trafalgar Square or at the Cenotaphâafter all, he had no idea how long he'd been gone. Perhaps they had closed the area around Parliament, it did seem that the riverbank was very quiet.

Growing out of this idea, which even as it formed in his mind quickly began to take on a dark edge, was a secondary realization. Where was the river traffic? Even on Remembrance Sunday, or something equally important, there would be commercial boats on the river, wouldn't there?

He looked ahead to the distant but growing shape of Westminster Bridge, unmistakable despite the shroud of mist, and an even more frightening thought suddenly came to him. Where was the Hunger-ford Bridge? If this was the Embankment coming up on the right, then the old railroad bridge should be right in front of him. He should be staring up at it right now.

He steered the rowboat toward the north bank, squinting. He could see the shape of one of the famous dolphin lampposts appear from the fog, and relief flooded through him: it was the Embankment, no question.

The next lamppost was bent in half, like a hairpin. All the rest were gone.

Twenty meters before him, the remains of this end of the Hunger-ford Bridge jutted from a shattered jumble of concrete. The girders had been twisted until they had stretched like licorice, then snapped. A ragged strip of railroad track protruded from the heights above, crimped like the foil from a candy wrapper.

As Paul stared, his mind a dark whirlpool in which no thought would remain stationary for more than an instant, the first large wave lifted the rowboat up, then set it down again. It was only as the second and third and fourth waves came, each greater than the one before, that Paul finally tore his eyes from the pathetic northern stub of the bridge and looked down the river. Something had just passed under Westminster Bridge, something as big as a building, but which nevertheless moved, and which was even now stretching back up to its full height, on a level with the upper stanchions of the bridge itself.

Paul could make no sense of the immense vision. It was like some absurd piece of modernist furniture, like a mobile version of the Lloyds Building. As it splashed closer, moving eastward along the Thames, he could see that it had three titanic legs which held up a vast complexity of struts and platforms. Above them curved a broad metal hood.

As he stared, dumbfounded, the thing stopped its progress for a moment and stood in the middle of the Thames like some horrible parody of a Seurat bather. With a hiss of hydraulics that Paul could hear clearly even at this distance, the mechanical thing lowered itself a little, almost crouching, then the great hood swiveled from side to side as though it were a head and the immense construct was looking for something. Steel cables which hung from the structures above the legs bunched and then dangled again, making whitecaps on the river's surface. Moments later, the thing rose back to full height and began stilting up the river once more, hissing and whirring as it moved toward him. Its passage, each stride eating dozens of meters, was astoundingly swift: while Paul was still locked in a kind of paralysis, his joy turned to nightmare in mere seconds, the thing sloshed past him, going upstream. The waves of its passage bounced the little boat roughly, thumping it so hard against the riverwall that Paul had the breath smashed out of him, but the great mechanical thing paid no more attention to Paul and his craft as it passed than he himself would have given to a wood chip floating in a puddle.