River of Blue Fire (79 page)

Read River of Blue Fire Online

Authors: Tad Williams

But as far as Sellars could tell, during the brief moments of investigation he had snatched between skirmishes with the Other, most of his small company still seemed to be alive within the network. Even more surprisingâbut his one real ray of hopeâwas that since this strange and protean enemy was so drawn to them, almost everything he could not discover of their position and situation from direct observation he could infer from the profusion of Other-related actions.

In other words, he had discovered that where the Other was most active on the network, the chances were good that Sellars' own people were nearby.

Not all of the centers of the Other's most frantic activity would be Renie Sulaweyo, Orlando Gardiner, and the others, but many of them clearly were. This was very good for Sellars, but he could only hope that Jongleur and the other Grail members had not noticed the anomaly.

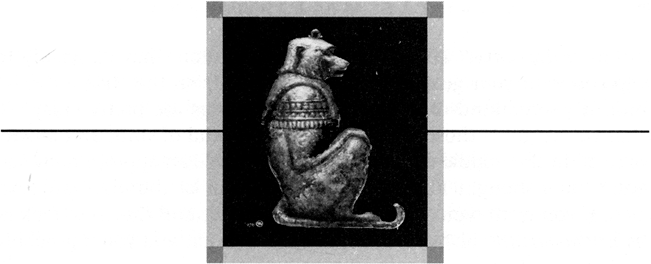

As the mists of his fatigue began to thin a little, Sellars saw that there had been several changes in the Garden since his last connection. Several fungal traces of the Other had broken the surface, and in one place several distinct subsets had come together overnight, localized now in an obscure and heretofore untouched section of his inside-out, green world. He wondered briefly if this new aggregation meant that some of the individual groups, who had been inexplicably separated a short time back, had found each other again. If so, that too might be a cause for hope. He also wondered if it was time to try to use the boy Cho-Cho again. He had not prepared the youth properly the last time, it was now clearâthe first emergence into the network had shocked him so badly there had been no point in going forward with the experimentâbut it had still been Sellars' greatest success since the Temilún fiasco, since the boy's description of the people he had seen had sounded very much like Irene Sulaweyo and her Bushman-baboon companion.

Sellars put the possibility aside for later consideration. Distracting the security system and then holding and hiding an access line long enough to get the boy through was horrifyingly hard work. He wasn't sure whether he was up to it again just yet.

He moved his focus on the Garden in and out, looking for patterns. The Other's latest fruiting bodies were also interesting. He could not tell yet what they symbolized, but it seemed to be moments of large expenditure of energy on the part of the network. He would run some analysis on them later, when he had finished with the larger picture.

Sellars moved with relief from the obscurities of what was happening within the Otherland system to the section of his Garden that represented things happening outside the Grail network, in RL, where information was more reliable and easier to interpret. Just in the last days there had been a rash of deaths and other occurrences, all related in some way to Otherland, so there was much new growth on those parts of the model.

A reasonably famous, but long-retired inventor of role-playing gear, rumored to have been given his own simulation on the Otherland network for services rendered, had been found dead of apparent heart failure; a group of children from the TreeHouse technocommune had fallen victim to Tandagore Syndrome; but most significantâand perhaps most troublesome for the Grail peopleâwas that a dozen research scientists in almost as many different countries had all been killed within a single eight-hour period.

The scientists had been felled by a variety of causes from cardiac failure to brain aneurysm, but Sellars knew (although the authorities had not yet admitted it) that each of them had been logged into an entomology facility sponsored by Hideki Kunoharaâa man with so many connections to Otherland that he himself had become a species of lichen within Sellars' Garden. Kunohara's online facility had experienced some kind of massive failure, although even the investigators' private conversations Sellars had managed to monitor suggested they had no idea how that collapse might be linked to the scientists' deaths.

The various propaganda arms of the Brotherhood were already moving to isolate and confuse the investigations, and with their immense resources might very well succeed, but even the fact of the failure having happened, with such spectacularly newsworthy results, was curious. Why would the Brotherhood allow so many prominent people to die on their network? Were the Grail brethren losing control of their own system? Or were they now too powerful, too far advanced in their plan, to care?

Each of these small botanical newcomers considered, both for itself and within the greater ecology, Sellars moved on.

As his systems collated information from the vast legion of resources he had linked to his Garden, new plants had sprouted and begun to grow almost unnoticed, but some had recently developed such robust size that he could not ignore them.

One represented a lawyer in Washington, affiliated to the Garden model through Salome Fredericks and Orlando, whose vegetable avatar was busy sending roots in all directions. Some of these roots had extended so fast and so far that Sellars himself was being constantly surprised by the new places he found them. This lawyer, Ramsey, was extending a search of his own through the information sphere almost as fast as Sellars could track him, and seemed to have made a large and symbiotic connection with the plant that symbolized Orlando Gardiner's own real-world system.

There was also mysterious activity flowering in Australian law-enforcement networks, which interacted both with the subgarden that represented the CircleâSellars knew he had a lot of thinking to do as far as the Circle were concerned, perhaps a day's gardening just for them aloneâas well as Jongleur, and even the fungal threads of the Other. He had no idea why that would be. More questions.

Irene Sulaweyo's real-world plant, far more available to observation than the one which symbolized her activities inside the Otherland network, had developed some disturbing tendencies as wellâstems extending at odd angles, leaves dying as the information they represented suddenly dried up. He dimly remembered that she had a dysfunctional family, and of course it had been her brother's coma which had brought her into this in the first place. Sellars could do nothing more for her online self than he was already doing, but he hoped that her physical body was safe, and made a note to see what he could learn about her situation.

Last, and most worrisome to him personally, was the shiny pale flower that represented little Christabel Sorensen. Until twenty-four hours ago, for all that he had put her through, despite all the risks he had brought to her, her blossom had been thriving. But he had been unable to contact her for two days, and she had not donned the access device he had given herâthe replacement Storybook Sunglassesâto answer his last call; his readings suggested they seemed to be broken or decommissioned. It might be something as simple as equipment failure, he knew, but a check of military base records showed that she had not been to school yesterday, and her father had called his own office to excuse himself for the day because of what the system listed as “family problems.”

It all worried him very much, not only for Christabel's sake, but for his own. He had exposed himself by being so dependent on the child, although he had seen no other option at the time. It was a grave weakness in his security.

The drooping petals of the Christabel-flower reproached him. The problem required a delicate investigation, and perhaps an equally delicate solution, but he did not have enough information yet about what had changed. He shifted his focus away.

Sellars was tiring now. He looked only briefly to the single green shoot that represented Paul Jonas. For a while, right until the moment Sellars had succeeded in his audacious plan to free Jonas into the system, the Jonas-stem had been the center of a tangled thicket of plans and actions. But now the man was gone, lost in the system beyond any of Sellars observational capabilities, and could no longer be acted upon. But the central Paul Jonas questions remained unanswered.

How could one man so endanger the Brotherhood that they would keep him a prisoner on the system and eradicate all proof that he had ever existed in the real world? Why would they not simply kill someone who was, for whatever reasons, such a threat to them? They had killed hundreds of others that Sellars knew of with certainty.

He felt a headache coming on. Still too much Garden, not enough toads.

It was all in flux, and although new patterns were forming he could not make sense of them yet. Some were cause for hope, but others filled him with despair. His spherical Garden represented the hopes and fears of billions of people, and the gamble Sellars had undertaken was a desperate one. A week from now, a month, would it still be a vigorous jungle? Or would rot have struck down all plants but the Brotherhood's, tumbled all other stalks and stems and leaves to the ground to become mulch for the venomous blooms of Felix Jongleur and his friends?

And what of Sellars' own secret? The one that even his few allies did not suspect, the one that even in the event of a most improbable and miraculous victory against the Grail, could still turn the Garden into a wasteland of ash and tainted soil?

He was only tormenting himself, he knew, and to no purpose: he did not have a moment's extra time or strength to spend on pointless worrying. If he was anything, he was a gardener, and whether the future brought him rain or drought, sun or frost, he could only take what was given to him and do his best.

Sellars pushed away the darkest thoughts and returned to his tasks.

CHAPTER 30

Death and Venice

NETFEED/NEWS: Chinese Say “Fax You!”

(visual: Jiun Bhao and Zheng opening Science and Technical Campus)

VO: Chinese Minister for Science Zheng Xiaoyu announced today that the Chinese have taken a huge leap forward in the race to perfect “teleportation” technology

â

the spontaneous transmission of matter, a favorite device of science fiction flicks. In a press conference during the opening ceremonies for the new Science and Technical Campus in T'ainan

â

formerly the National Cheng Kung University

â

Zheng announced that Chinese researchers were close to solving the “antiparticle symmetry problem,” and that he had no doubt matter transport, also known as teleportation, would be a reality within a generation, perhaps as early as the middle of next decade. Doctor Hannah Gannidi of Cambridge University is not so optimistic.

(visual; Dr. Gannidi in her office.)

GANNIDI: “They haven't let us see much, and what we've seen has a lot of questions attached to it. I'm not saying they may not have made some important progress

â

some of Zheng's people are really excellent

â

but I wouldn't be planning to fax yourself home for the holidays just yet

. . .

”

T

HE masks of Comedy and Tragedy bobbed toward him through the darkened basilica, but when he most needed to move, fear seemed to have pulled the bones right out of Paul's legs and back. The terrible pair had found him againâwould they hunt him until the end of time?

“Don't move, Jonas,” narrow-faced Tragedy crooned. “We have lots of lovely, squeezy things planned for you.”

“Or we might just rip you apart,” suggested Comedy.

A third voice, a silent compulsion which brushed along his nerve endings like a chill breeze, urged him to give upâto fall where he stood and let the inevitable happen. What was the point of flight? Did he really think he could elude these two tireless pursuers forever?

Paul clutched at the wall for support. Some force that emanated from these two was poisoning him, slowing the heart within his chest. He could feel his fingers, his hands and arms and legs, all growing cold, stiff . . .

Gally!

The boy was still sleeping in the woman Eleanora's rooms. If they captured Paul, what was to keep them from taking him as well?

The realization sparked something at the base of his brain and sent a charge of rigidity down his spine. He staggered back another step, then found his balance and turned. For a moment he could not remember in which direction Eleanora's apartment lay; the enervating dread that seeped from the pair behind him threatened once more to pull him down. He chose what he thought was the right direction and flung himself forward down the shadowed corridor. Within seconds the compulsion to surrender became less, but he could still feel the pair following behind him. It was terrifying and yet also strangely unreal, a nightmare of flight and pursuit.

Why don't they just capture me?

he wondered.

If they're the masters of this network, why don't they surround me, or turn off my sim, or something?

He ran faster, risking a fall on the slippery floors. It was stupid to torment himself with unanswerable questionsâbetter to snatch at freedom while he could.

But they're getting closer each time

, he realized.

Each time

.

Paul recognized a familiar wall hanging: he had guessed correctly. A moment later he was pounding on the apartment door, which fell open a few inches before hitting some obstruction. He heard Gally's voice inside, a rising sound of confusion and question, so he put his shoulder down and shoved as hard as he could. The door held for a moment, then the impediment slid to one side, scraping on the flagstones, and Paul tumbled into the room. Eleanora huddled in a corner with wide-eyed Gally pulled close against her.

“You left me!” Paul shouted. “You left me to those . . . things!”

“I came to save the boy,” the small woman snapped. “He means something to me.”

“You think piling . . . furniture against the door is going to . . . to keep them out?” He was breathing so hard he could hardly talk, and already the sense of imminent attack was growing again. “We have to get out of here. If you can't get me offline, can you at least get us to another simulation? Make a . . . a gateway, whatever those things are called.”

“No.” She shook her head, her wizened face tight. “If I summon an emergency gateway to interfere with Jongleur's agents, the Brotherhood will know. This is not my fight. This Venice is all I have left. I will not risk it all for you, a stranger.”

Paul could not believe he was standing there arguing, while Death and Destruction breathed down his neck. “But what about the boy? What about Gally? They'll take him, too!”

She stared at him, then at the child. “Take him and run, then,” she replied. “There is a hidden doorway that will let you out to the square. Tinto said the nearest gateways were with the Jews or the Crusaders. The Ghetto is a long distanceâall the way to the middle of Cannaregio. Better to go to the Crusader hospital. If you are lucky, you can outrun those things long enough to get there and find the gate.”

“And how am I supposed to find this Crusader place?”

“The boy will show you.” She leaned down and kissed Gally on top of his head, mussed his hair with an almost fierce affection, then shoved him toward Paul. “Through my bedchamber. I will make it look as though you forced your way in.”

“But you own this place!” Paul grabbed the boy's arm and pulled him toward the chamber door. “You sound as though you're afraid of them.”

“Everyone is afraid of them. Hurry now.”

They came out of the constricted passageway bent almost double, running so low that Paul was practically on all fours. As they burst out into the lampbright confusion of St. Mark's Square, Gally careened into a crowd of revelers, which caused much staggering, cursing, and spilling of drink. Following close behind, Paul ran into one of the reeling strangers, tumbling both the man and himself to the ground.

“Gally!” he shouted, struggling to rise. “Gally, wait!”

He and the stranger were entangled in each other's cloaks. As Paul tried to fight free, the other man clipped him on the ear, crying, “Damn you, leave off!” He shoved the man back to the ground, then bounded over him, but the man grabbed at his foot and tripped him. He did not regain his balance for a dozen steps; by the time he did, the crowd had closed in around him once more and he could see no sign of the boy.

“Gally! Gypsy!”

As he shouted, an invisible

something

touched him, raising his hackles like a cold hand on the back of his neck. He whirled to see movement in the dark arches along the side of St. Mark's churchâtwo white faces swiveling in the shadows. The masks seemed to float bodiless above the dark robes, like will-o-the-wisps.

A hand closed on his wrist, real flesh this time, and Paul gasped. “What are you doing?” Gally demanded. “You can't fight. We have to run!”

It was only as he clamped shut his sagging jaw and followed the boy into the festival night that Paul realized how true the boy's words were: he had left his sword behind in Eleanora's apartments.

Gally led them north across the square, around or sometimes straight through knots of merrymakers. Where the boy could force his way through to no more reaction than a curse or a half-hearted kick, Paul was not so lucky; by the time he reached the edge of the square he had been forced to flee several offers of violence, and had lost track of his small guide once more. Also, a look back for their pursuers provided new worries: a group of armed pikemen were spilling out of the Doge's palace at a swift trot, and had already begun to fan out across St. Mark's Square with a very purposeful air. It seemed the dreadful two were not going to rely solely on their own stalking skills.

“Paul!” the boy called from a colonnade near the great clock tower at the edge of the square. “This way.” As Paul followed, he slipped down a narrow passage, through a courtyard, and then out onto a winding street where rows of market stalls were still lively with custom despite the hour. Several hundred meters from the square, Gally at last ducked into an even smaller alley. On the far side, he crossed the dark street and clambered down to a path along the bank of a canal.

“They've sent soldiers after us, too,” Paul panted as he scrambled down a stone staircase and joined him. He dropped his voice as a group of shadowy figures floated past in an unsteady boat, singing. “It's a good thing there are so many people out.” He paused. “You called me by my name, didn't you? Do you remember me now?”

“A bit.” The boy made a fretful noise. “Don't know. I suppose so. Come on, we have to hurry. We can double back to the Grand Canal, find a boat no one's using . . .”

Paul put a hand on his shoulder. “Hang on a bit. That's the main route through this place, and it's also the one certain way out. They'll be looking for us all along that canal. Is there another route we can take to this Crusader hospital?”

Gally shrugged. “We can go more or less straight across the cityâcut through the corner of Castello district and into Cannaregio.”

“Good. Let's do it.”

“It's pretty dark through there,” Gally said dubiously. “Rough, too, you know? If we get killed in Castello, it probably won't be the duke's soldiers who do it.”

“We'll take the chanceâanything's better than getting caught by those two . . . things.”

Gally set out at a near-sprint, with Paul just behind him. The boy turned east along the small canal, and followed it until it curved away north again, then led them across a bridge over the river that flowed behind the ducal palace and St. Mark's. A few people were still making their way in toward the heart of Carnival, the square and the Grand Canal, but the boy had been rightâthe streets in this part of the city were emptier and darker, with only an occasional lamp to be seen burning in a window. The narrow, cobbled byways seemed too tight here for a deep breath, the buildings looming close on both sides as though threatening to tumble in and crush them. Only occasional faint voices and the smells of food cooking spoke of life hidden behind the walls, but the fronts of the houses were as secretive as masks.

As Paul struggled to stay close to the boy, who moved through the alleys and along the canals with the surefootedness of a cat, he fought to make sense out of what was happening. Those two creatures, Finch and Mullet, as something in him still wanted to call them, although his memory of those incarnations was dim, had followed him from one world to anotherâno, from one simulation to the next. But they clearly did not know where he was within any given simulation, nor was merely locating himâmaking visual contactâenough for them to capture him.

So what did that mean? For one thing, their powers, even as servants of the Grail Brotherhood, were not limitless. That much was clear.

In fact, the Grail people don't seem to have much of an advantage over anyone else in these simulations

, he reflected.

Otherwise, they could have just found me a long time ago, done some kind of search through their network and pinpointed me, like a lost file

.

There was something there, something to give hope. The lords of the Brotherhood might be terrifyingly rich and ruthlessâgods, in a wayâbut even within their own creation, they were not all-powerful. They could be fooled or eluded. That was more than merely something, he realized: if true, it was a very important idea.

He was jogging along on autopilot, hardly aware of his surroundings, when Gally stopped so suddenly that Paul almost knocked them both down. The boy waved his hands violently, demanding quiet. At first he could not understand why they had stopped. They were a few hundred meters east of the Palace River and had just turned into what by Venetian terms was a fairly wide street, but silent and with only a single lantern hanging above a door at the far end to ease the darkness. A thick, ground-level mist made the buildings seem to float, as though Paul and the boy stood in the middle of one of the canals instead of a cobbled street.

“What. . . ?”

Gally slapped at his arm to silence him. A moment later Paul heard a slurry murmur of voices, then an array of distorted shadows suddenly appeared between them and the lantern, several figures walking abreast, moving with a certain unhurried precision.

“Soldiers!” Paul hissed. “There must be a side street in the middle.”

Gally tugged at his arm, pulling him back the direction they had come. When they reached the end of the street, the boy hesitated for a moment, then drew them down another alley to let the soldiers pass, but instead of continuing on toward St. Mark's, the small troop swung into the alley as though magnetized to the fugitives. Paul cursed silently. The odds were quite hopelessâat least a dozen soldiers in helmets and breastplates filled the passage, pikes on shoulders, boots kicking eddies in the mist.