Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey (27 page)

Read Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey Online

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Philosophy, #TRV025000

Texas was the first Gulf Coast state to outlaw old-style entangling nets, then Florida. At the time of our conversation, Alabama, not often known for its environmental foresight, was about to make a similar change because of the demonstrable evidence that modified nets help increase the number of mullet — once the staple fish of Florida — and species dependent on them.

Cooper said, “This spring I saw the largest school of mullet I’ve ever seen, and it’s due to the new nets. And that increase has happened even with some illegal fishing still going on.” He nodded toward a fenced area. “Right now, over there, we’ve got two illegal nets we picked up just recently. The technology we have today to apprehend outlaw fishing has surpassed the capacity to harvest illegally. Without governmental enforcement, certain fish would be seriously reduced and others of them would be gone.”

He took us inside the fenced area and showed us two big rolls of entangling nets. I asked who still used such things. “Mostly older men going out at night,” Cooper said. “When we come up to their boats, they tell us the fish jumped into the boat because those guys know courts require evidence of an illegal net

being used.

Just having possession of the fish isn’t illegal.”

Despite the misleading name, the new regulation did not ban nets, but it did require reduced size of both the total area of a net and the openings in the mesh, and it limited the use of nets to only two at a time. Those changes necessitated more hand casts, a bodily demanding task that made some fishermen no longer want to expend the effort, while others simply resented having to change their old ways.

An opinion I’d heard the day before now made sense: a man who once used the old netting method told me he thought the young were too soft to go after mullet and the old were now too down in the back for it. His words seemed to reflect what I’d encountered that morning at Pouncey’s Restaurant in Perry where a woman supervising several teenagers on an outing wore a T-shirt embossed with:

WORK HARD!

NO ONE EVER DROWN

IN THERE OWN SWEAT

Karen Parker said of the coastal town forty miles south of Steinhatchee, “People in Cedar Key have switched to clamming with some success. And the University of Florida offers a course in developing commercial clamming-beds that can produce a harvest in eighteen months. It’s a renewable resource. They call it Clamalot. But I haven’t heard yet of anyone in Steinhatchee taking part.”

Cedar Key — once a port on an early cross-Florida railroad and a center for the manufacture of wooden pencils — has an economic and cultural history quite different from the more isolated and insulated Steinhatchee from whence much of the timber for pencils came. (Many an American learned to write with a stick of Steinhatchee forest in hand.)

“The talk today in Cedar Key isn’t about a net ban,” Parker said. “People there are more concerned about preventing pollutants from wiping out the economic advances they’ve made with clamming. They see their situation much differently today.” She paused to phrase her words. “When people have to start changing established ways, it’s difficult anywhere, and some communities resist it — maybe I should say

feel

it — more than others. But when it comes to the new fishing regulations, there’s help all around to make the transition easier.”

Resistance to transition in Steinhatchee cropped up one night a couple of years earlier when a conservation agent, out of uniform, went into the local lounge, a place where, during the day, I’d seen elderly women playing Scrabble. Recognized, the agent caught a barrage of hostility and was soon dragged into the parking lot and beaten before he could break free and cross the road to the river. He leaped in and swam to the other side. There, a young woman saw the battered man and, in apparent sympathy, offered him a lift. She promptly returned him to the parking lot where he was battered again. He recovered, and the new regulations remained unchanged, but he’d provided an evening’s diversion for men who preferred altercation to alteration.

Various agencies created several programs to assist commercial fishermen affected by the new provisions, including a standing offer to buy their old, illegal nets, as well as unemployment benefits and job retraining in both aquaculture and agriculture. People elsewhere around the Gulf who shifted to clamming or crabbing could bring in good pay, and so could those fishing for mullet with redesigned nets, but they were people who believed “no one ever drown in there own sweat.”

Still, at night in Deadman Bay, violators were going out in their bird-dog boats, a number of them motivated as much by the thrill of risk as by a quest for money. After all, when darkness comes down in the Steinhatchee country, some people can’t come up with much to amuse themselves, and a game of cat-and-mouse on the water or a fox-and-hound high-speed chase over dirt roads through the timber plantations can provide stories for several evenings at the lounge. It was almost as good as beating up a conservation agent. And, in a fashion similar to Appalachian moonshiners of another era, law versus outlaw was a contest where a hot-blooded fellow could try to make himself into a local legend.

The Steinhatchee story, as I came to see it, was of a village being changed not by a misnamed “net ban” but by a juggernaut of increasing human population and the refusal of people both there and elsewhere to set and follow reasonable guidelines for realty development. The true enemy of Steinhatchee was not some governmental agency imagined to be after private land; it was blind stubbornness and — even more — greed. In those ways, many of the residents themselves were active participants in a full-momentum — if doomed — pursuit of the quick-and-easy.

My guess is that Steinhatchee and Jena were headed toward a new order — one initially more prosperous, at least for outside investors — but one that would soon enough further impoverish their lives emotionally and spiritually, because the forces they were embracing rarely accommodate native traditions and values like those developed locally over generations. But if anger, hopeless resignation, anomie, and unconsidered acceptance of the steamrollers of contemporary Florida could be replaced by common sense, imagination, and wise leadership, a seemingly implacable new American economy might be turned to serve the people.

But first they would have to show a resilience capable of forming a future rather than being flattened by one. Instead of simply reviling aquaculture, how about trying it? Instead of living beyond the law, how about finding the benefits of living within it? And what about considering the implications of Steinhatchee Landing where native traditions of northern Florida Cracker architecture had been reinterpreted sympathetically along the river to create new jobs and a sound pillar in the local economy?

The right choice in Steinhatchee, I concluded, was not to continue fighting to resurrect doomed ways but to shape a future to honor and enhance the most salubrious aspects of their past where lay innovative avenues rather than roads to nowhere. The choice at Deadman Bay, as across the nation, was whether to comprehend and reshape history or to continue the current course and become history.

Maybe it was even beginning to happen. In Perry, I picked up a leaflet with the headline

JUST SAY NO!

NO BOMBING RANGE

NO MISSILES ON OUR NATURE COAST

Below was this: “Save our health, the environment, our homes, and our property values!” The sheet was a response to a plan to move the bombing range at Eglin Air Force Base east of Pensacola (one of the largest forested military bases in the world) a couple of hundred miles southeast to the timberlands north of Steinhatchee. The leaflet said, “We have a new developer in Taylor County who stands to get rich quick if he can pull off a land-swap deal with the military. We get the bombs and he gets the beach.”

The Truth About Bobbie Cheryl

A

COUPLE OF DAYS EARLIER,

on our last evening together in

Steinhatchee, I asked Mo before he headed home whether his quest for watermen’s taverns was succeeding. I said we hadn’t come upon any in Steinhatchee, and the most likely spot for one there was a lounge where ladies played Scrabble in the afternoon and conservation agents got thrashed at night. “I think we hit Steinhatchee too late,” he said. “We missed out on the fish-houses and the whole culture connected to them. Maybe I’ll just write a book called

Too Late.

That should about cover it all.”

I suggested his revised title was a reminder we’d better get ourselves up to North Carolina before we’d be saying the same about Bobbie Cheryl’s Anchor Inn. Hadn’t the dream of that Great Good Place helped us through those sorry days of Phuddom? We owed it an honorary visit. After all, Miss Bobbie Cheryl wasn’t going to live forever.

“Miss?” he said, surprised. “Bobby Sherrill’s no miss. He’s a guy.” Mo looked at me as if I’d just popped out with something about Shakespeare’s latest novel. He spoke kindly, taking his time to let me down gently. “Didn’t you ever catch on? We needed a dream, an escape. Bobby Sherrill’s Anchor Inn was my invention. I concocted it to save us. It was an anchor for a couple of guys adrift on a sea of near insanity.” He put his hand on my shoulder, as he does from time to time. “And it worked, at least for you,” he said, “because it was mythical.” He paused again. “Even if it really did exist, would you want to find it?”

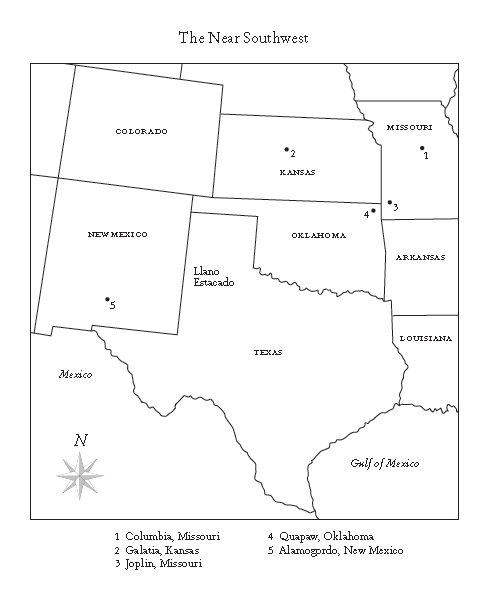

Into the Southwest

Into the Southwest

On a Ring of Light

1. Apologia to Camerado Reader

2. That Batch from Down Behind Otis

3. In the Light of Ghosts

4. A Poetical History of Satan

5. Gladiator Without a Sword

6. God Help the Jury

7. A Triangle Becomes a Polygon

8. Though Dead, He Speaks

9. Dance of the Hobs

10. How Tadpoles Become Serpents

11. Last Train Out of Land’s End

12. A Quest for Querques

13. One-Hundred-Seventeen Square Feet

14. After the Fuse Blows

On a Ring of Light

The next day the Indian told me their name for this light —

Artoosoqu’

— and on my inquiring concerning the will-o’-the-wisp, and the like phenomena, he said that his “folks” sometimes saw fires passing along at various heights, even as high as the trees, and making a noise. I was prepared after this to hear of the most startling and unimagined phenomena witnessed by “his folks”; they are abroad at all hours and seasons in scenes so unfrequented by white men. Nature must have made a thousand revelations to them which are still secrets to us.

I did not regret my not having seen this before, since I now saw it under circumstances so favorable. I was in just the frame of mind to see something wonderful [that night], and this was a phenomenon adequate to my circumstances and expectation, and it put me on the alert to see more like it. I let science slide, and rejoiced in that light as if it had been a fellow-creature. I saw that it was excellent, and was very glad to know that it was so cheap. A scientific

explanation,

as it is called, would have been altogether out of place there. That is for pale daylight. Science with its

retorts

would have put me to sleep; it was the opportunity to be ignorant that I improved. It suggested to me that there was something to be seen if one had eyes. It made a believer of me more than before. I believed that the woods were not tenantless, but choke-full of honest spirits as good as myself any day — not an empty chamber in which chemistry was left to work alone, but an inhabited house — and for a few moments I enjoyed fellowship with them. Your so-called wise man goes trying to persuade himself that there is no entity there but himself and his traps, but it is a great deal easier to believe the truth. It suggested, too, that the same experience always gives birth to the same sort of belief or religion. One revelation has been made to the Indian, another to the white man. I have much to learn of the Indian, nothing of the missionary. I am not sure but all that would tempt me to teach the Indian my religion would be his promise to teach me

his.

Long enough I had heard of irrelevant things; now at length I was glad to make acquaintance with the light that dwells in rotten wood. Where is all your knowledge gone to? It evaporates completely, for it has no depth.

— Henry David Thoreau,

The Maine Woods,

1864

Apologia to Camerado Reader

N

EVER, YOUNG AUTHORS,

open your story with another writer’s words. I, being young only in comparison to mud or a Galápagos tortoise, have earned — at least in my own mind — the liberty of violating the axiom. Exceptions prove rules, so it’s said. Here’s my contravention, this from the eighteenth century, from Laurence Sterne’s

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman:

Of all the several ways of beginning a book which are now in practice throughout the known world, I am confident my own way of doing it is the best — I’m sure it is the most religious — for I begin with writing the first sentence — and trusting to Almighty God for the second.