Rogue Heroes: The History of the SAS, Britain's Secret Special Forces Unit That Sabotaged the Nazis and Changed the Nature of War (16 page)

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #World War II, #History, #True Crime, #Espionage, #Europe, #Military, #Great Britain

—

With Jalo now back in enemy hands, the SAS and LRDG needed a new forward base from which to continue desert operations. The most logical was the oasis at Siwa, thirty miles inside Egypt from the Libyan border in the eastern part of the Great Sand Sea, on the edge of the Qattara Depression. A former fortress of the Senussi tribe, built around the ancient Greek temple of Ammon, Siwa Oasis was a far cry from the mosquito-ridden discomfort of Jalo. Clear natural springs frothed out of the ground, creating a vivid splash of greenery in the desert, with towering date palms and neatly tended olive groves. Cleopatra herself was said to have swum in the natural stone pool fed by a hot spring. There were a few European houses, as well as a sprawl of traditional villagers’ huts. Fitzroy Maclean was enchanted by Cleopatra’s Pool and immediately jumped into it: “Under palm trees were pools of clear water bubbling up from great depth…it was like bathing in soda water.”

Stirling’s attention had turned to Benghazi. For more than 2,500 years, competing forces had fought over the ancient Mediterranean seaport: Greeks, Spartans, Persians, Egyptians, Romans, Vandals, Arabs, and Turks. The Italians had invaded in 1912, ruthlessly oppressing the locals and building a charming seafront of Italianate villas. Benghazi flourished as a showcase for Mussolini’s imperialist vision, and by 1939 some twenty thousand Italians were living in this thriving colony with shops, restaurants, and a cinema. In February 1941, it had been captured from the Italians by British and Commonwealth forces in the first major Allied military action of the Western Desert campaign. Two months later it was recaptured by Rommel’s Afrika Korps. The port was seized back by the Allies on Christmas Eve, only to change hands once again barely a month later as Rommel’s forces swept eastward. A vital target in the see-saw war, Benghazi and its surrounding airfields had taken on strong symbolic, as well as strategic, significance. With Tobruk back in Allied hands, Benghazi was the essential supply port for the Afrika Korps, while the nearby airfields—Berka, Benina, Barce, Slonta, and Regima—were vital to the Axis air forces in the battle for air supremacy over the Mediterranean.

The primary focus of that battle was Malta, now under intense siege from the Axis air forces. As the only Allied base between Gibraltar and Alexandria, the island was regarded, by both sides, as militarily essential, a key to victory. Between 1940 and 1942, the Luftwaffe and the Italian air force would launch some three thousand bombing raids, many from the airfields around Benghazi, in an effort to batter and starve Malta into submission, by attacking its ports, towns, and cities, as well as Allied shipping supplying the island. Churchill believed that, if Malta surrendered, the German hold on the Mediterranean would be absolute, its supply lines invulnerable, and Egypt would be next to fall. Rommel was equally convinced that, if Malta withstood the onslaught, the war would eventually swing in favor of the Allies. In May 1941, the German commander observed: “Without Malta the Axis will end by losing control of North Africa.” If the Benghazi airfields and harbor could be neutralized, or at least seriously impeded, then Malta might hold out.

—

Benghazi was a bustling town, filled with men in the uniforms of many nations. Recent experience suggested that the more crowded a target, the less conspicuous would be a team of saboteurs. After two occupations, the British Army had a clear idea of the layout of the town; there was even an elaborate and detailed scale model of Benghazi in the intelligence headquarters at Alexandria. The large harbor on the Gulf of Sirte was usually packed with enemy vessels. Once again, Stirling planned to use portable boats in order to mount an assault on the vessels at anchor, which would demonstrate to HQ that L Detachment was capable of destroying ships as well as planes, petrol tankers, and warehouses. Just a few weeks earlier, the plan would have been rejected as harebrained, but with the two armies hunkered down across the Gazala Line, and Churchill demanding a counterattack, Auchinleck was keen to show that offensive operations were continuing. Here was a double opportunity: to disrupt Axis supply lines and relieve the pressure on Malta. Stirling was authorized to mount an attack on Benghazi—or at least ascertain whether such an operation was feasible—during the next moonless period, starting after March 10, 1942. Three other SAS raiding parties would mount simultaneous attacks on the nearby airfields.

This time, the raiders would not go by parachute, LRDG truck, or even on foot. Instead, Stirling planned to drive into the middle of Benghazi in his own customized car.

In one of those canny acts of larceny for which the SAS had a natural aptitude, the unit “obtained” a Ford V-8 station wagon, with a powerful engine, two rows of three seats, and a top speed of seventy miles per hour. Painted Wehrmacht gray, and with the roof and windows removed, it looked, from the air, like a German staff car. The Germans painted a “recognition signal,” which changed every month, on the hoods of military vehicles to prevent attack from their own planes. British intelligence supplied the relevant signal. Machine guns could be mounted fore and aft, but unclipped and laid on the floor when necessary, to give the vehicle a “more innocent appearance.” The attacking convoy set off from Siwa on March 15, with Stirling in the lead, proudly driving his “Blitz Buggy.”

The Jebel mountain range rises about forty miles south of Benghazi. The hills enjoyed sufficient rainfall to sustain abundant plant life; the shrubs and small trees made it ideal terrain in which to hide up and prepare for the attack. Verdant foothills ran down some twenty-five miles to an escarpment overlooking the coastal plain, beyond which, some fifteen miles distant, lay Benghazi. The landscape reminded Paddy Mayne of the South Downs. “Low hills and valleys, lots of wild flowers and long grass,” he wrote to his brother. “It’s like a picnic.” The area was sparsely inhabited by the Senussi (both a tribe and religious order), many of whom felt a passionate hatred of their Italian colonial overlords, little admiration for the Germans, and a corresponding affinity for the British.

The Jebel was also home to many spies. The Middle East branch of the British intelligence service, working under the vague title of the Inter-Services Liaison Department, had arranged for the LRDG to transport its agents behind the lines. Some of these had been living among the tribespeople for months, disguised as Arabs, recruiting local informants, gathering intelligence on what was happening in Benghazi and the surrounding areas, and sending this back by wireless. Shortly before Stirling’s arrival, the LRDG had bused in the latest team of British spies, led by agent 52901, “a Jewish academic in his 60s” who spoke fluent Arabic, to link up with “friendly sheiks and report troop movements around Benghazi.” The Germans and Italians, however, had their own undercover agents in the Jebel, where a small but intense espionage battle was under way. Whenever British troops appeared, small groups of Senussi would emerge, magically, out of the undergrowth, to trade eggs, cigarettes, and information. Most seemed friendly. Some were certainly working for the other side. And a few, undoubtedly, were working for both. The tricky task for the British agents in the Jebel was to sort out which was which.

In the Jebel foothills, the raiding parties split up: Mayne headed toward Berka, which had both a main aerodrome and a satellite airfield, while Fraser set out for Barce, in the northeast, an administrative center built around an old Turkish fort. Another team targeted Slonta airfield, away to the east.

Stirling’s first foray into Benghazi was a complete failure. The rubber boats refused to inflate, and a high wind would have made launching them impossible anyway. The mission was aborted, but not before Stirling had made a thorough inspection of the harbor.

The others had not fared much better. Slonta was too heavily guarded to risk an attack. Fraser found only one plane to destroy at Barce. The team attacking Berka had not been able to locate the main airfield. Only Paddy Mayne met with success, blowing up fifteen planes on the satellite airfield at Berka, before hiding out with a friendly group of Bedouin encamped a few miles from the target. The next morning, by sheer fluke, one of the men from the LRDG turned up, looking to buy a chicken from the Arabs, and led the SAS men back to the rendezvous. “Never disbelieve in luck again, or coincidence,” Mayne wrote to his brother. Bravery and ingenuity were vital to Mayne’s success and survival; what is less often noted, though it was arguably a greater factor than all the others, was his astonishing good fortune. “I’d rather have a lucky general than a smart general. They win battles,” Eisenhower once said, echoing Napoleon. Mayne’s willingness to take chances no one else would contemplate was balanced by his extraordinary good luck.

An impromptu party was held the next night in the desert, “with rum and lime, rum and tea, rum omelette, and just plain rum.” Paddy Mayne was the most enthusiastic participant. Once drunk, according to a report on the operation, “Capt. Mayne went through the weird rites of demonstrating how one should not fire at night: machine guns, light machine guns, tommy guns, pistols, and God knows what other intricate pieces of mechanism.” The desert exploded with noise as Mayne loosed off every gun he could find into the night sky, and then fell asleep in the sand. The War Diary report concludes: “Casualties: Incredible as it may seem, nil.”

Stirling was not downhearted by his own failure to destroy anything. This had been more of a reconnaissance operation than a full-scale raid, an opportunity “to spy out the land for an eventual large scale operation.” The nighttime visit to Benghazi had proved that the Axis forces were unprepared for the kind of tactics adopted by Stirling: with enough chutzpah, and the right weather conditions, one could drive into the middle of the town and wreak havoc. This Stirling now proposed to do, in one of the most audacious (and hilarious) operations of the war. This time he would be taking with him additional bombs, inflatable boats, and the son of Winston Churchill.

David Stirling, founder of the SAS.

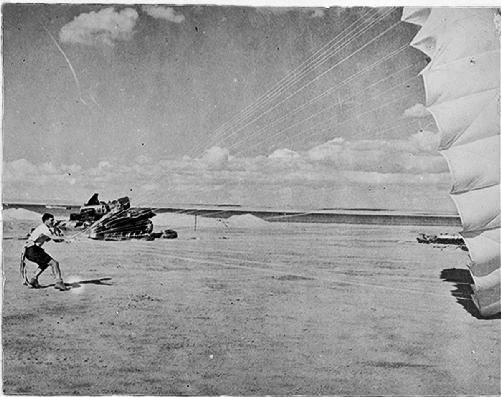

Before a desert raid. Stirling standing at right.

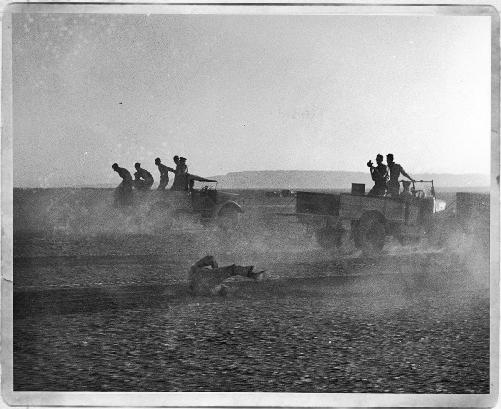

Leaping from the back of a vehicle driving at thirty miles per hour was, Stirling believed, a good way to simulate a parachute landing.